New Paragraph

Published: March 2024

Group Work

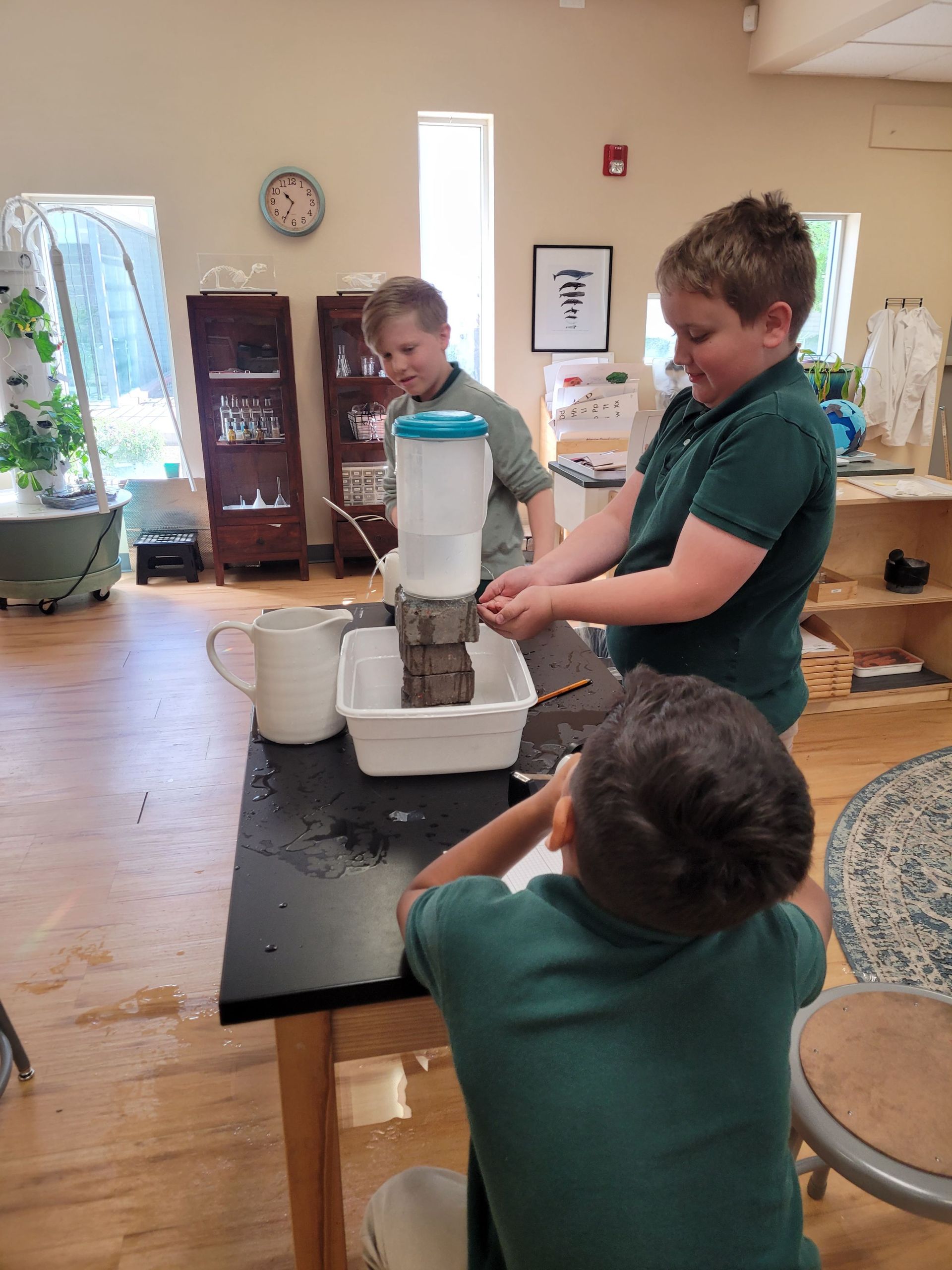

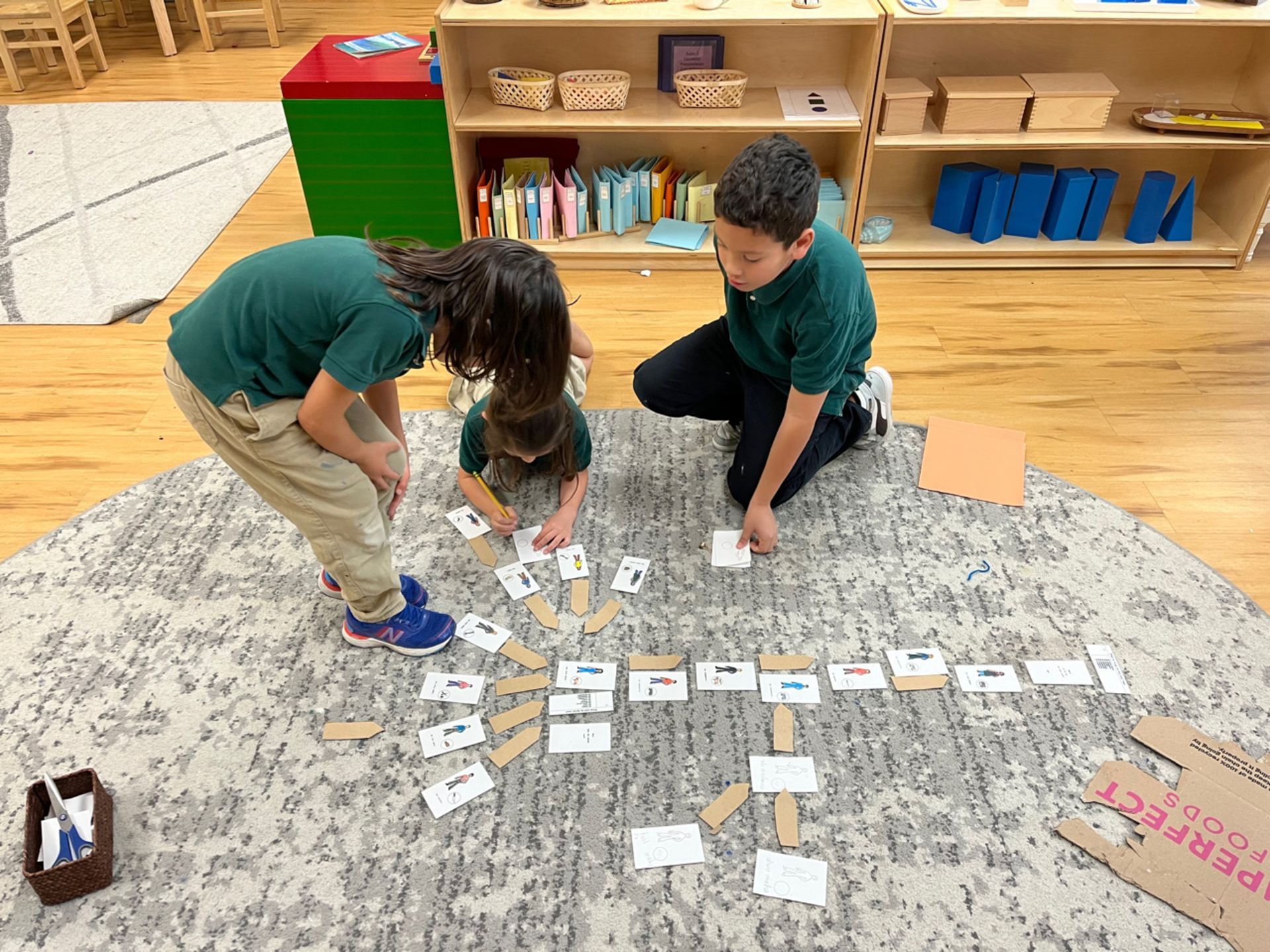

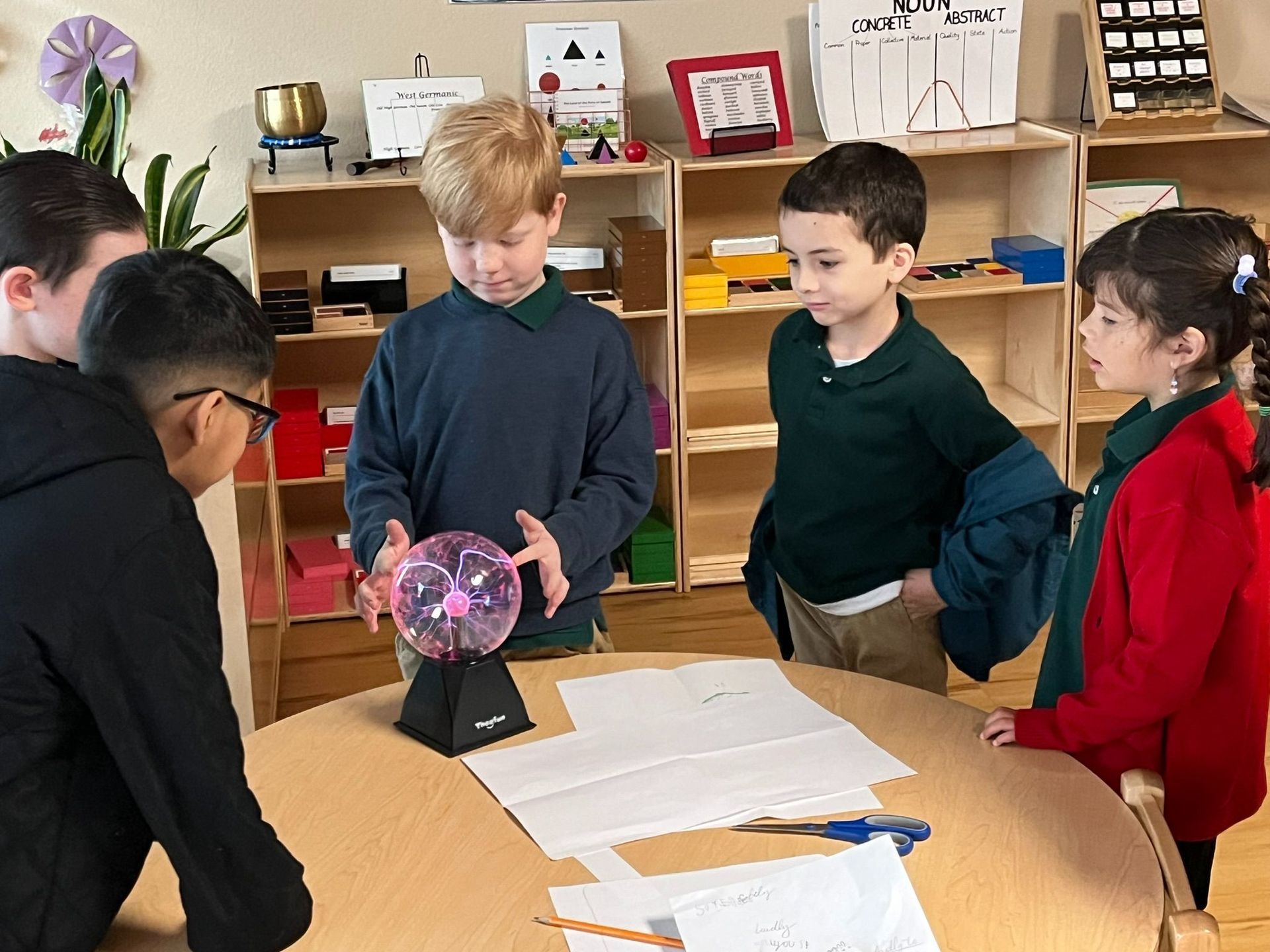

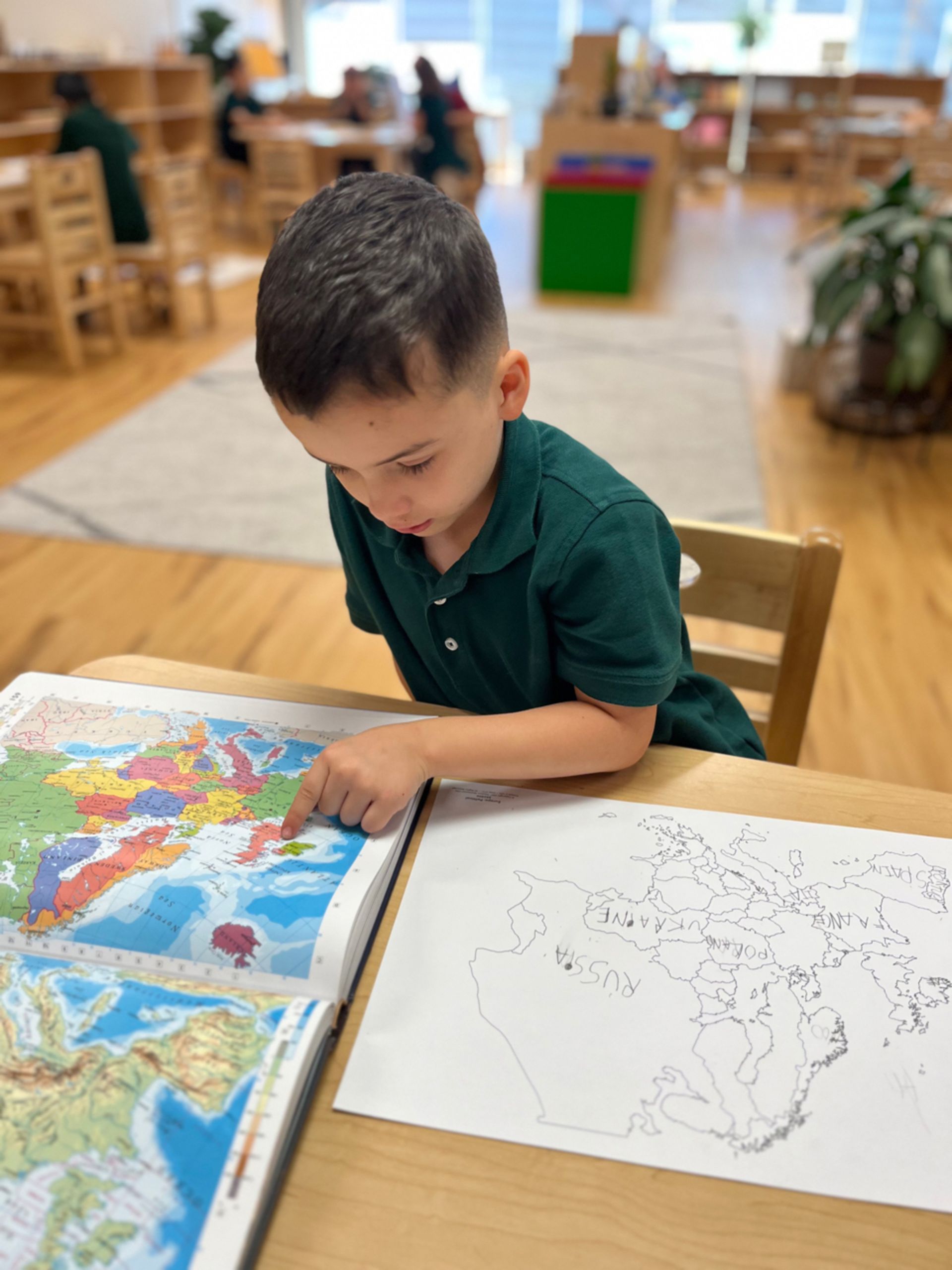

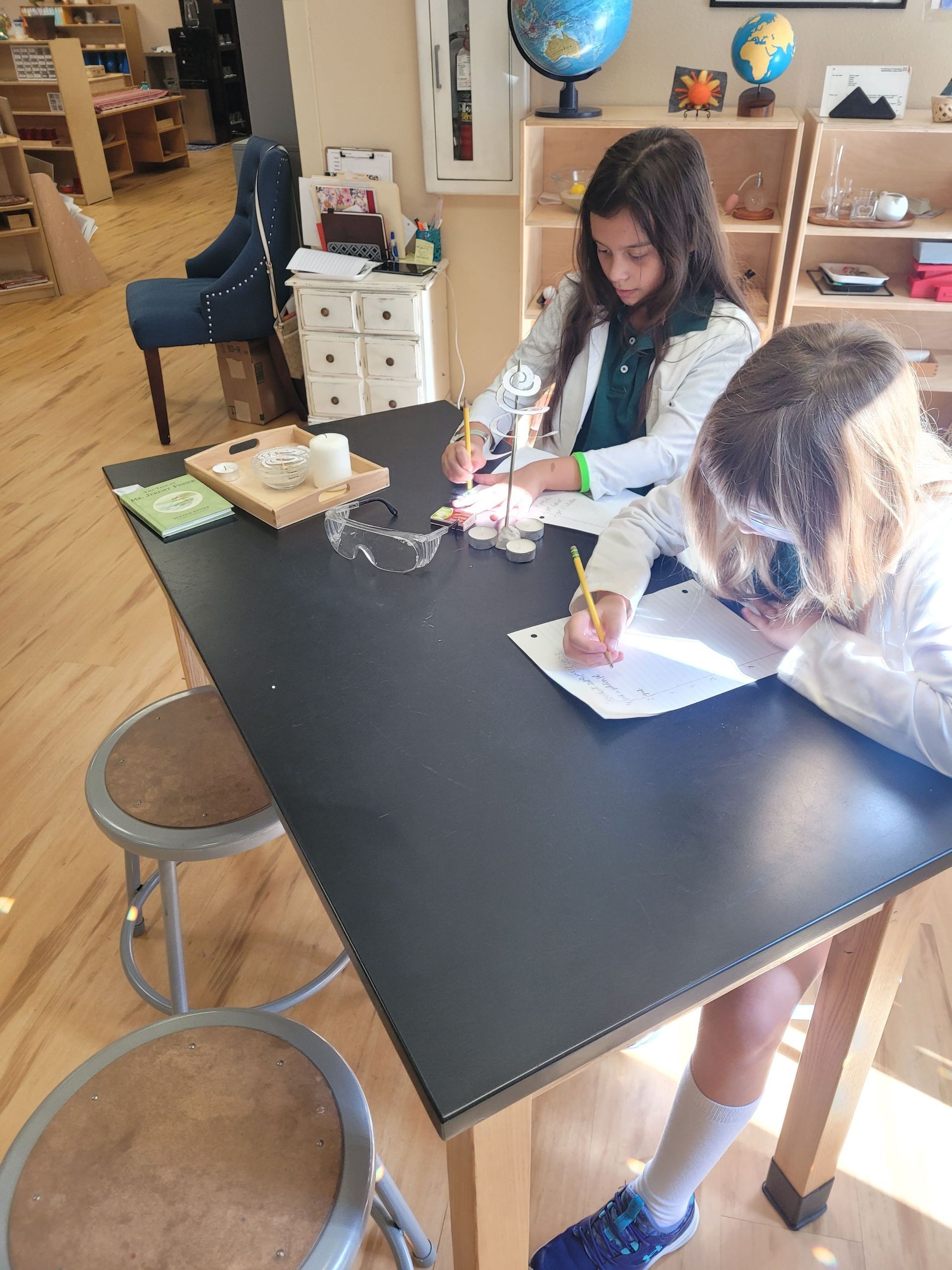

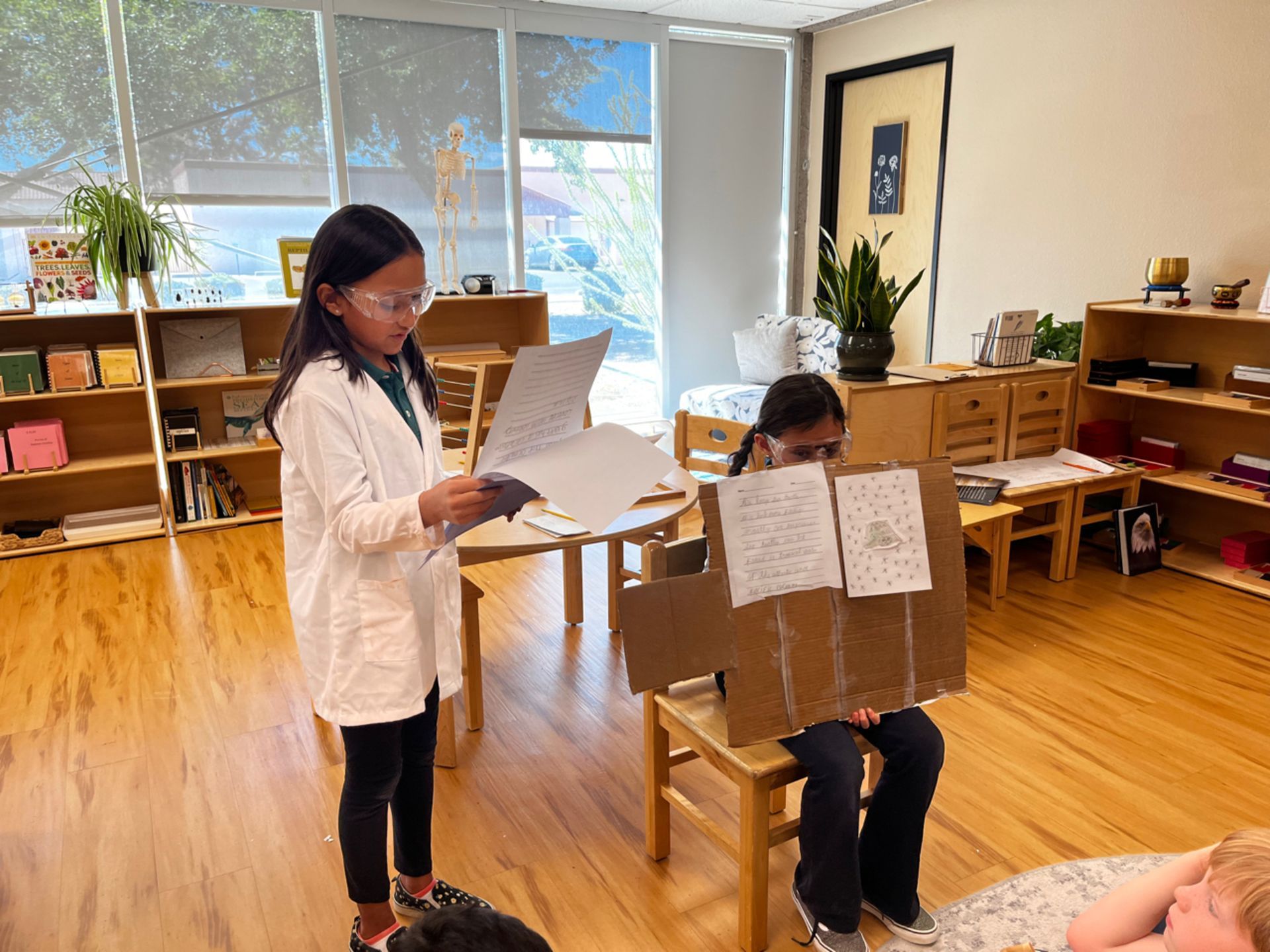

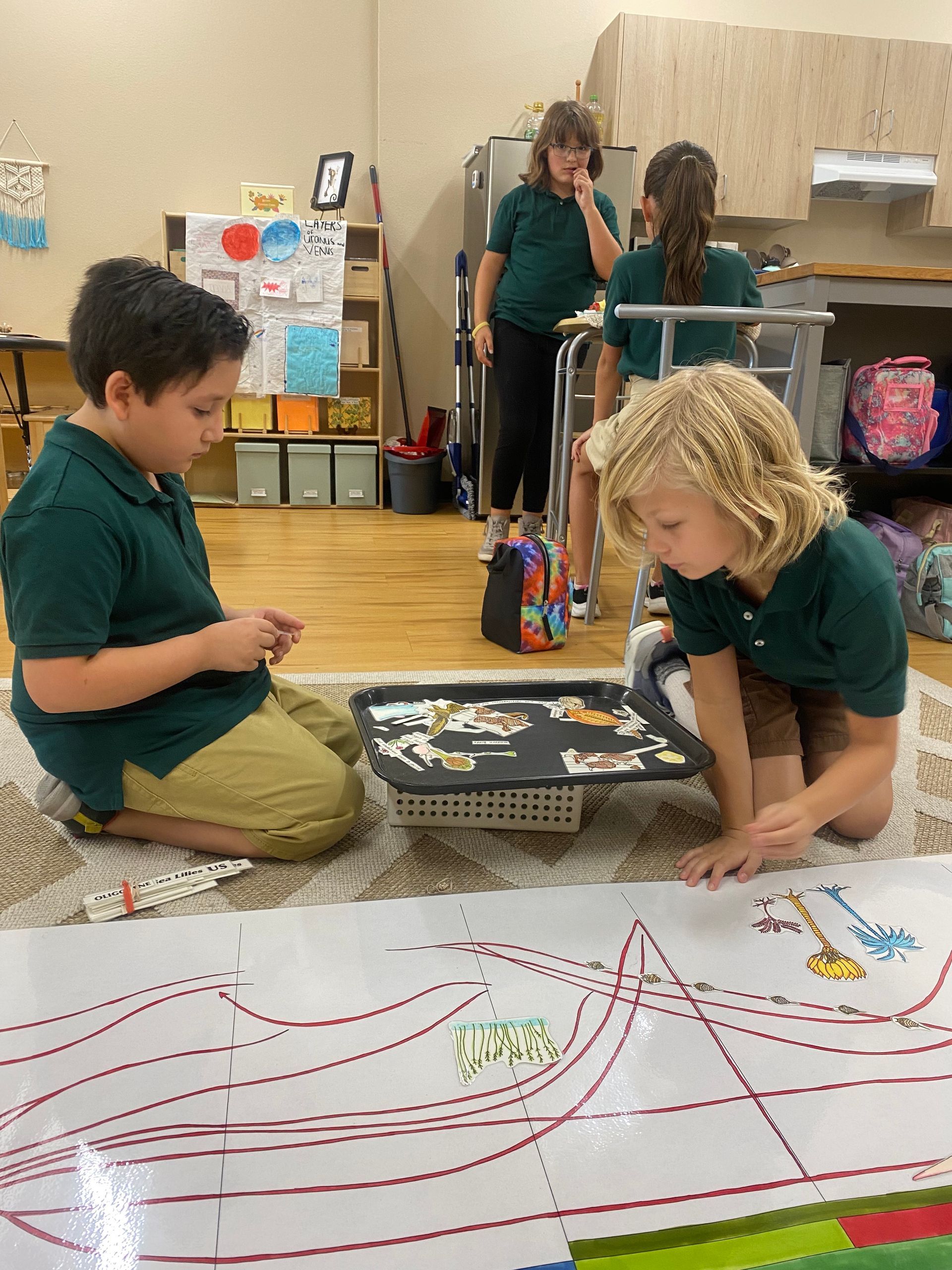

Maria Montessori's educational philosophy places a strong emphasis on the significance of group work in elementary classrooms, viewing it as essential for both social and academic development. Montessori observed that even young children demonstrate a natural inclination to engage in structured activities within groups, highlighting humanity's innate tendency towards organization and collaboration. This insight forms the foundation of Montessori education, where group work serves as a cornerstone of learning.

“[An] interesting fact to be observed in the child of six is his need to associate himself with others, not merely for the sake of company, but in some sort of organized activity. He likes to mix with others in a group wherein each has a different status. A leader is chosen, and is obeyed, and a strong group is formed. This is a natural tendency, through which mankind becomes organized. ” Maria Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential, p. 4

Central to Montessori's concept of group work is the recognition of each child's unique role within the collective. In a well-functioning group, individuals assume varying roles, fostering a sense of order and responsibility among participants. Montessori believed that such group experiences not only enhance academic learning but also cultivate essential social skills and emotional intelligence.

Montessori also emphasized the importance of personal discipline within group contexts. Unlike conventional notions of success focused on individual achievement, Montessori asserted that true fulfillment arises from the collective success of the group. By prioritizing the group's well-being over personal accolades, children learn the value of collaboration, empathy, and mutual support, fostering a sense of camaraderie and interconnectedness among peers.

“… the individual thinks more about the success of his group than of his own personal success. ” Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, p. 213.

In the Montessori classroom, group work extends beyond academic collaboration to mirror societal dynamics. Through structured activities and cooperative projects, children learn to navigate interpersonal relationships and contribute meaningfully to their communities. Montessori's holistic approach to education recognizes the interdependence between individual growth and collective well-being, preparing students to become compassionate and socially responsible citizens capable of making meaningful contributions to society.

In conclusion, Maria Montessori's profound insights into group work not only underscore the transformative power of collaboration and communal learning but also evoke a sense of hope and possibility. By embracing the natural inclination of children to engage in organized activities within groups, Montessori education fosters environments where every individual's unique strengths are celebrated and valued. Through group work, children not only develop essential academic skills but also cultivate virtues like empathy, cooperation, and leadership, shaping them into compassionate and socially conscious individuals. As we reflect on Montessori's vision, we are reminded that every child has the potential to contribute meaningfully to their communities and beyond, bringing connection, joy, and positive change to the world.

Hattie Harris

Lower Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published February 2024

The Reasoning Mind

One of the standout features of children at the elementary age is their developing reasoning mind. Consider the power of imagination as the engine that powers a child’s journey to intellectual independence, and the reasoning mind as the wheels that propel them forward. This developmental stage is all about children beginning to use logical thinking to understand the world around them. Maria Montessori once emphasized the importance of this stage, suggesting that it is about learning to think, not just absorbing facts.

In Montessori classrooms, everything is designed to support this growth. The year starts with the five great stories, which impressionistically unveil the Creation of the Universe, the Coming of the Earth, Humans, Languages, and Numbers. These stories lay the groundwork, sparking curiosity and leading to big questions like, "Why does the Universe exist?" and "How do we stay grounded on Earth?" It's a way to ignite children's imaginations and encourage them to dive deeper. Following these stories, children engage in activities that let them seek answers firsthand, nurturing a love for learning and discovery.

As children grow, their questions evolve. Younger children in primary often ask, "What is this?" while elementary children start pondering the "why" and "how" of things. In a Montessori space, children are guided to find answers through exploration and discovery. For instance, when curious about how many days there are until Christmas, rather than giving a direct answer, a teacher might point them toward a calendar. This not only teaches them to find answers on their own but could also open a learning moment of history or timekeeping.

In the Montessori classroom, the development of the reasoning mind extends beyond academic exploration to include social and moral growth. An illustrative example of this is the lunchtime routine. During this time, students are tasked with selecting lunch helpers and planning out their roles, a process that requires them to apply logical thinking and collaboration. This scenario teaches them about responsibility, teamwork, and the intricacies of decision-making. By engaging in these activities, students use their reasoning minds to consider the needs and viewpoints of others, balance different roles, and come to collective decisions. This hands-on approach to learning not only fosters a sense of community but also sharpens their ability to think through complex, real-world problems — a direct application of the reasoning mind in social contexts.

Montessori students also extend their learning beyond the classroom through "going-out" activities. These are research activities inspired by their interests, like visiting the Desert Botanical Garden to see how plants adapt to harsh climates. But here's the twist: they plan it themselves, from stating their purpose to organizing the day. It’s a practical application of their reasoning skills, marking their first steps towards independence in the real world.

In essence, the Montessori method is about nurturing curious, analytical minds ready to tackle the challenges of the world. Through storytelling, self-led exploration, and real-world experiences, children learn to question, analyze, and engage with their environment. This balanced approach prepares them not only academically but also as thoughtful, independent individuals ready to contribute to society. Witnessing the growth of these young thinkers serves as a powerful testament to the impact of an education that values the development of the reasoning mind, equipping children for both school and life beyond.

James Qiao

Lower Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published: January, 2023

The Human Tendencies & the Psychological Characteristics of the Elementary Child

“ As we have seen, tendencies do not change and human tendencies are hereditary. The child possess them in potentiality at birth, and makes use of them to build an individual suited to his time.”

Mario Montessori, The Human Tendencies and Montessori Education

Dr. Montessori observed that all people have certain tendencies, which she identified as the Human Tendencies. These tendencies stay with them throughout their lives. People also have certain Psychological Characteristics which change depending on which plane of development they are in. In the Second

Plane of Development, the 6-12 child displays characteristics that are specific to their age group, while also displaying the universal human tendencies.

In the classroom we must consider these human tendencies when setting up the environment and preparing the child to be within it. We prepare them by supporting their reasoning mind, intellect, and will. The will is formed through making choices, seeing the resulting consequences, and understanding how the choices affect them and their community. This develops the will of the child. The choices children make must be based on knowledge, and the knowledge they need should be in the environment. We first want to get the child used to the environment and want them to understand what the classroom expectations are. This is done through orientation.

The first tendency is “to Orient”. Orientation is the ability to create order in the mind, knowing how to do things or where things are. In the classroom if the child knows how the community runs and where things are it helps them to be oriented. It creates independence and trust within the environment and with those in it. With orientation, we start out at an individual level in the First Plane of Development and then expand out to society in the Second Plane. This tendency is addressed in the beginning of the year so the children can adjust and adapt quickly to the classroom environment. When entering a new environment, be it a classroom or at home, children need to be able to orient themselves to their surrounds. They will need to know what the expectations are.

Another tendency is “to Order”. Order builds the mind through the classification of information, concepts and terminology. Children in the First Plane don’t know how things work but learn through experience and repetition. To help the child we must give lessons related to something they know or something we have done before. If things are given randomly the intellect of the child will not build properly. In the Second Plane, we are building on the intellect and want concepts to be introduced in an orderly way. We give reminders of what we have done and ideas of how we will build on that knowledge.

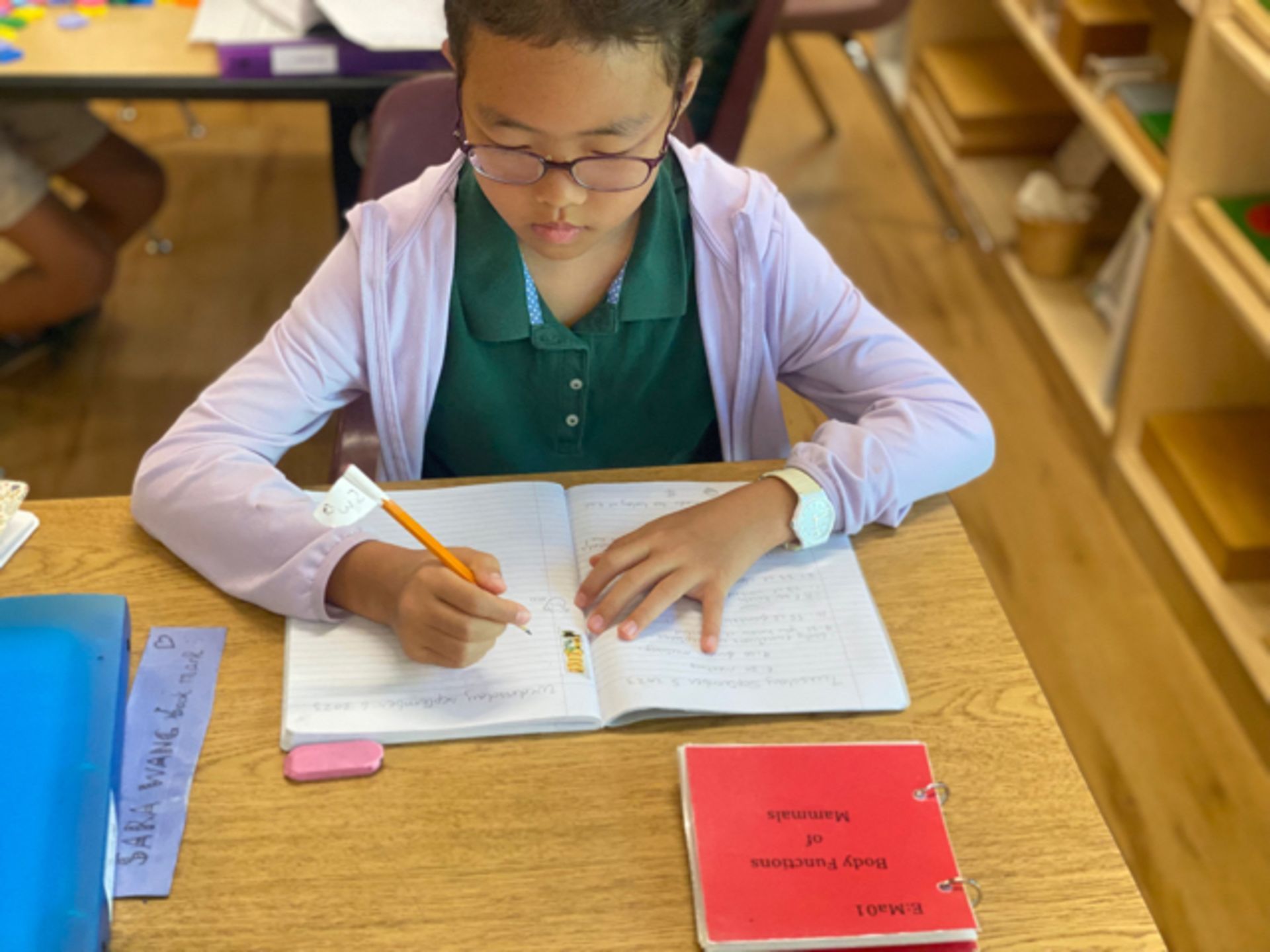

Next we have the tendency “to Communicate”. Communication uses language as a tool. It gives us power to pass on information. We can sit to create words to express what is in our mind and relate it to ideas. Children in the Second Plane have a reasoning mind and language helps the child develop ways of thinking, expressing themselves, and developing reasoned opinions. Communication is necessary for cooperation in social life. This will be manifested through the children talking. The conversations, discussions and conflicts the children have will further enhance their growth of language. It also helps their communication with others and enables them to share their thoughts and ideas. In fact, it is a necessary tool for collaboration and the sharing of ideas. Without communication the intellect will not grow properly.

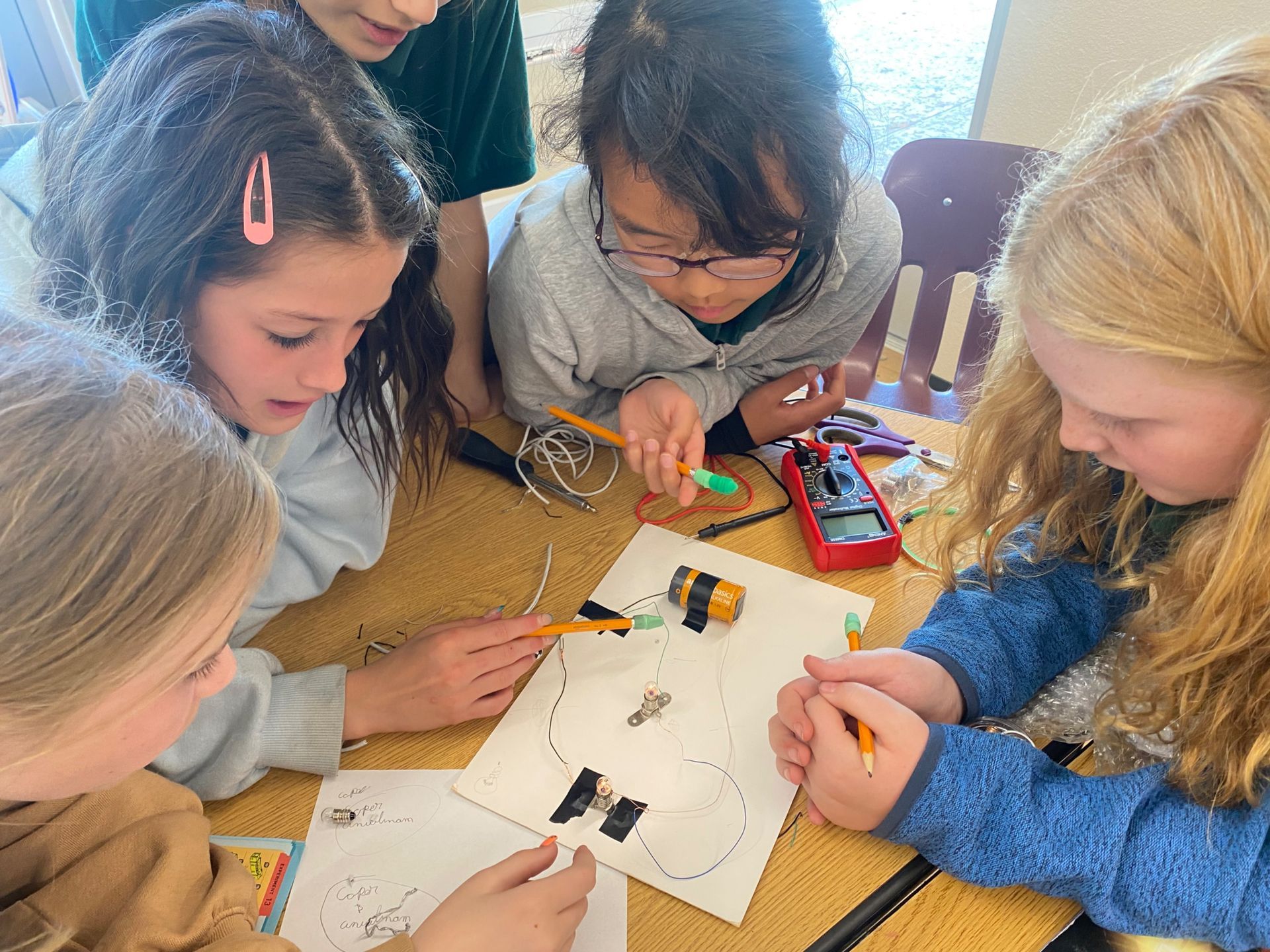

Montessori also recognized the tendency for “Exploration”. In the First Plane the child must be oriented before going into exploration. They will explore sensorially to find discoveries and understanding. In the Second Plane the child uses their reasoning mind and their imagination to explore. The classroom materials become less concrete and more symbolic. We must understand the psychology of the child in order to best support their needs to explore.

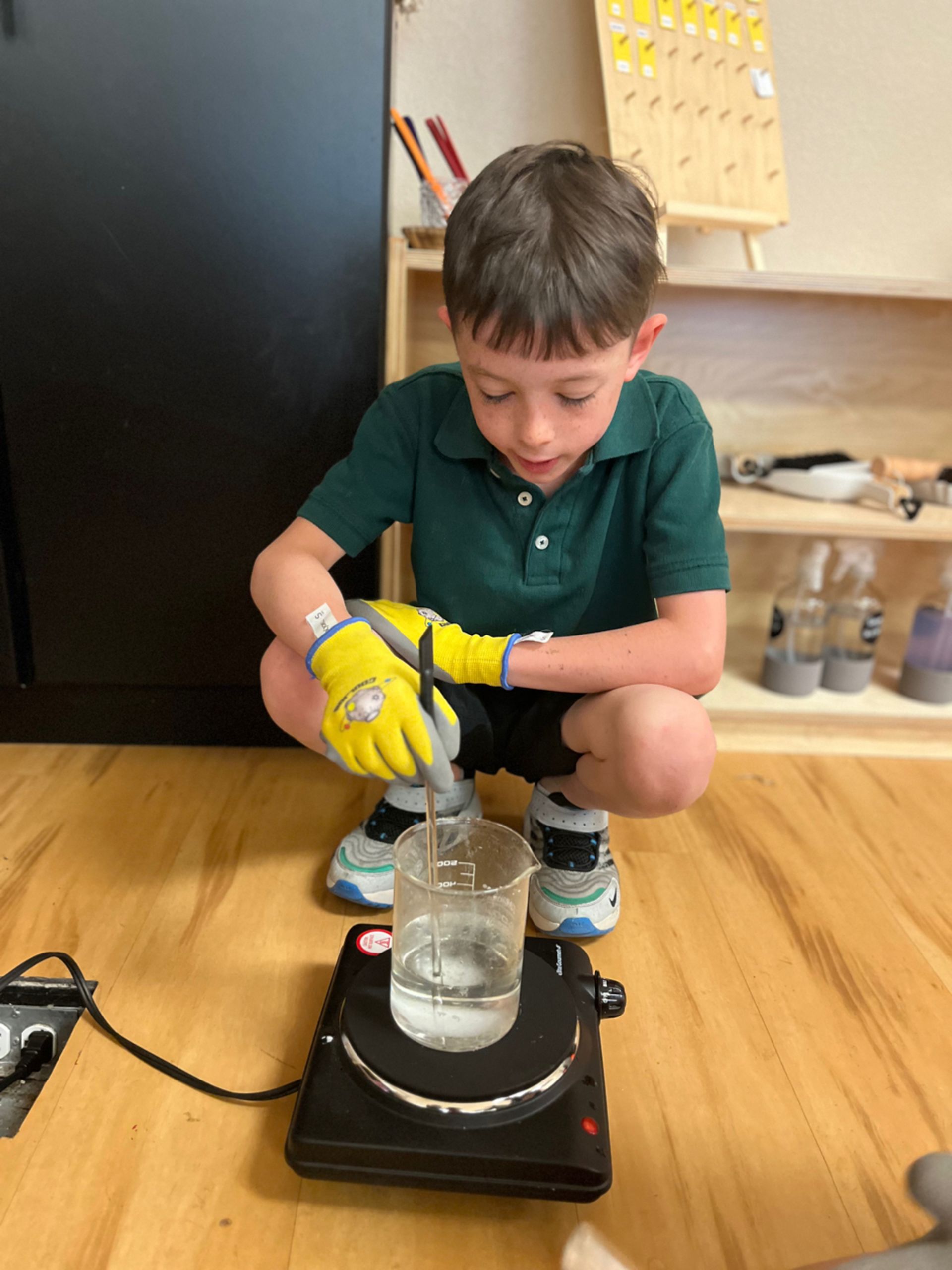

There is also the tendency “ to Work”. Work is a positive thing which allows us to have concentration in activity. The child will be doing activity with a purpose. This gives a fulfillment to personal goals. Deep concentration and self-satisfying work is key to health development. These activities, goals and deep concentration will lead us to normality throughout our lives.

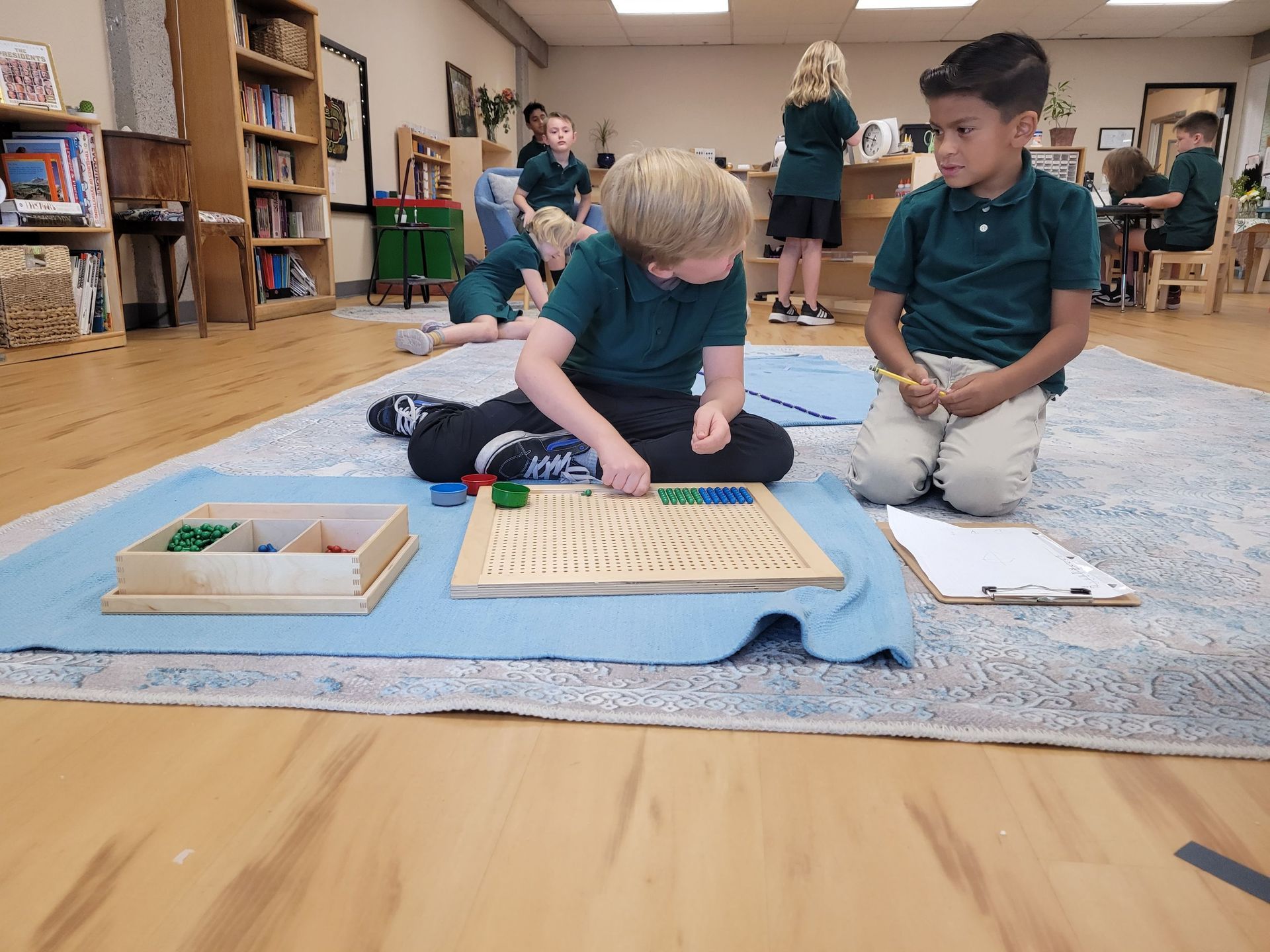

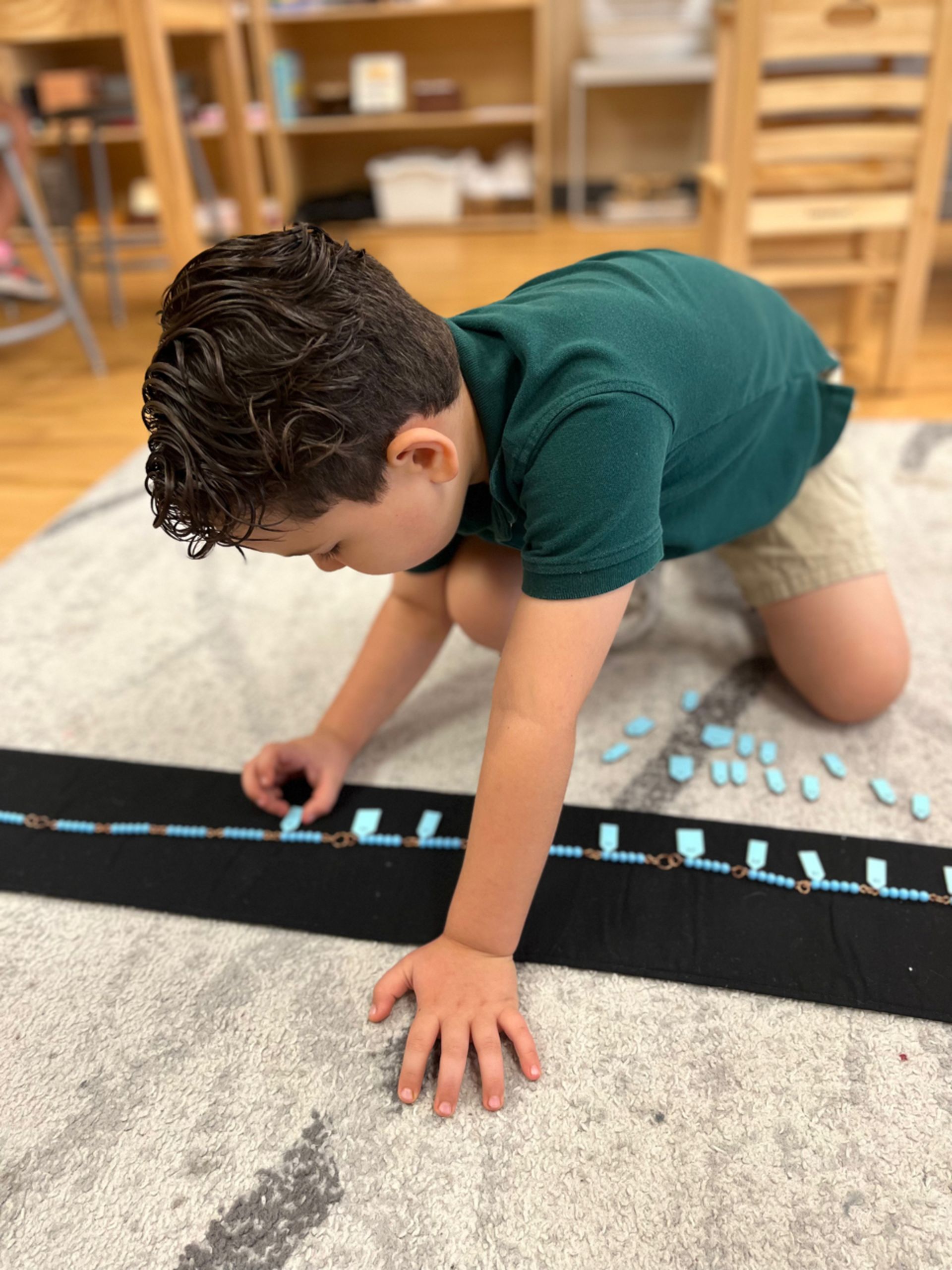

“Repetition” is another recognized tendency. As humans we learn best through repetition. Learning each time through errors that can be changed and perfected. This gives birth to creativity and exploration. The First Plane child does things over and over, without tiring until they reach an inner satisfaction. In Elementary the child isn’t so inclined to do things with the same amount of repetition. The will to repeat comes through variety and making things bigger and bigger; this is called amplification. We see this in the large group work children do in the elementary classroom. They will want to do bigger math problems, large scale timelines, measurements, lists and more.

In order to improve ourselves we need to make mistakes and learn from them, this is part of the tendency “to Self Perfect”. We must derive satisfaction on an individual level by doing better. Each individual has different aspects of themselves that they strive to perfect. As guides, we can help the child to be more aware by asking them “is this your best?’ If we ask in the right way the child usually responds honestly in their self-assessment. This will bring the child to work at the highest level they can reach. In the classroom environment, having consistent individual meetings with the children can help them to assess their own performance within the class.

The Children in the Second Plane also have a a tendency for “Exactness”. Everyone has a different type of exactness. We should honor the child’s way of finding it but also encourage them to take it to the next level. As guides in the classroom we are always making observations of this. If you want to replicate something it needs to be exact. If we have an idea in mind it has to conform to what exists in reality. Our Montessori material helps lead the children in exactness. Showing the child how to check their own work helps them to find their own error and correct it. In Elementary classroom the materials do not have a built in control of error, as they do in the Primary class, which is why we teach the child how to check their own work. This could be through reverse operations in math or using an editing chart for their rough draft writing.

“Abstraction” is another tendency. This is formed within our head and is not something you can touch. Language comes with this, you have an idea and it’s going to need a name. We rely on pulling out the essence of the thought or idea to reach this. It is important for the child to have had sensorial experiences in order to reach this abstraction. First to understand the material in the concrete or sensorial and gradually becoming more symbolic. As it is in their work, children go from concrete to abstract once they have internalized a concept or idea and the material is no longer needed. It is purely in the mind or worked out on paper.

The last tendency is that of “Activity”. Activity is manipulation with the hands. It drives us from idleness to productivity. By using our hands we are connecting to the material in a fundamental way. This can be done using Montessori materials, follow up work, or hand work.

The Human Tendencies have been broken down into separate characteristics to explain them in context, however they all run parallel and contribute to each other. It is the role of the guide to integrate observations and knowledge for the child and to put into practice these tendencies to guide them to being a fulfilled and complete human being. We will know that we have helped meet these tendencies of the children when they become productive workers, respect the environment, and follow established expectations. The children will continue to work towards improving themselves as the will and intellect guide them.

April Knight

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: December 2023

Going Out

“When the child goes out, it is the world itself that offers itself to them. Let us take the child out to show them real things instead of making objects which represent ideas and closing them up in cupboards.” — Maria Montessori

The 'going out' concept is essential for the delivery of cosmic education. 'Going out' is a term unique to Montessori, and although it implies an outing, it distinguishes itself from conventional excursions or field trips through its distinctive characteristics.

What are going outs?

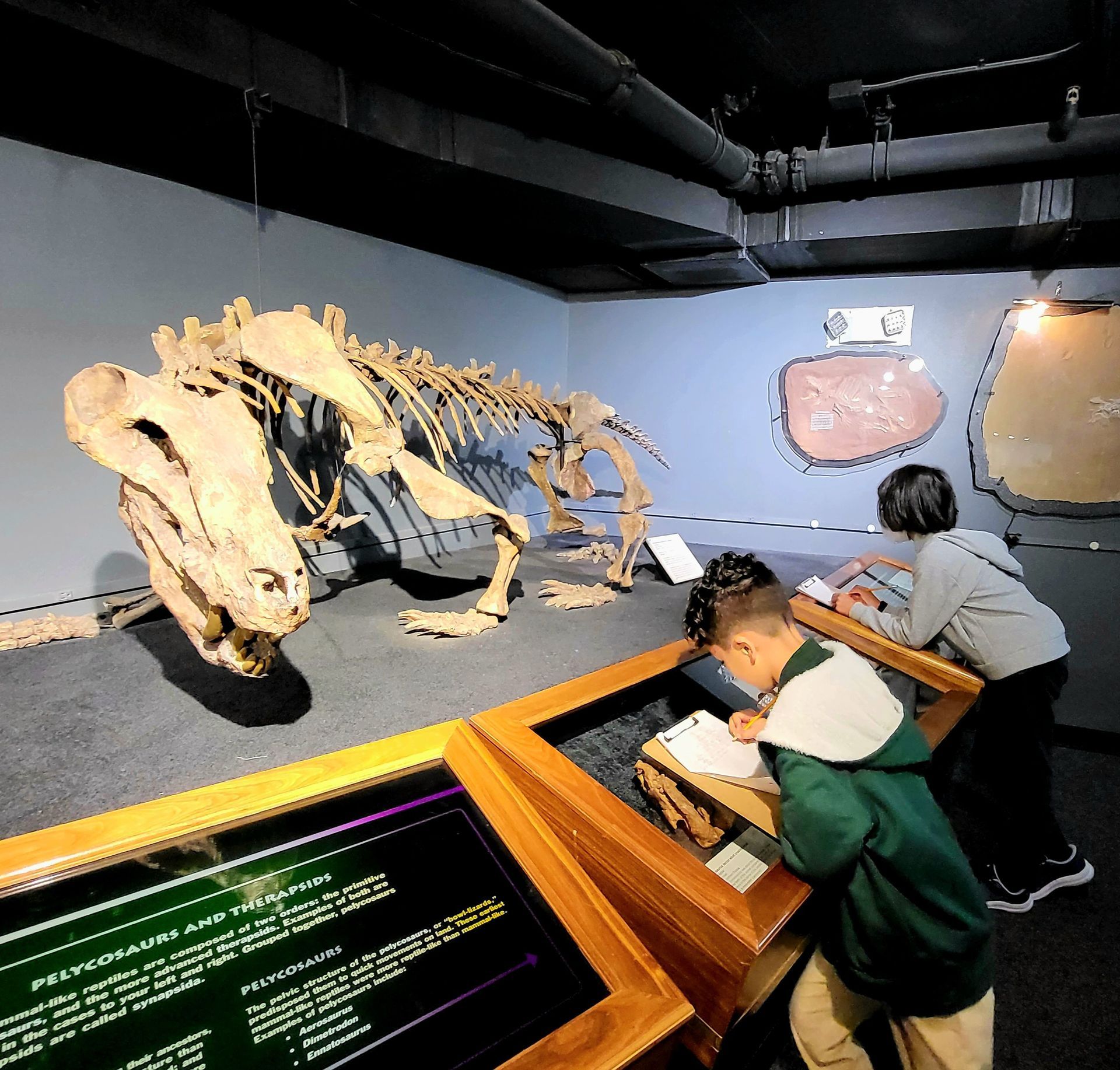

Imagine we are studying a particular topic in the class, like the coming of life. Children become very engaged and they want to learn more about ammonites. After researching and using all the books available in the class, there are still many things they want to learn about. At this point, they can organize a going out to discover more about ammonites. Each child plays a role in this organization; they need to look for a place where they can get more information, how to get there and who can take them, how much it costs, when they can go, what the schedule of the place is… They also need to prepare the questions for the expert. They are the ones who decide if they are going out and where they are going. They do this work collaboratively and without the interference of the adult. Then, after all the planning, the day arrives! Children go to the place and gather the information they need. The adult who is with them, the chaperone, should not intervene in their decisions, neither tell them what to do, they won’t give directions or buy them anything. They are there just to accompany the children and make sure they are safe.

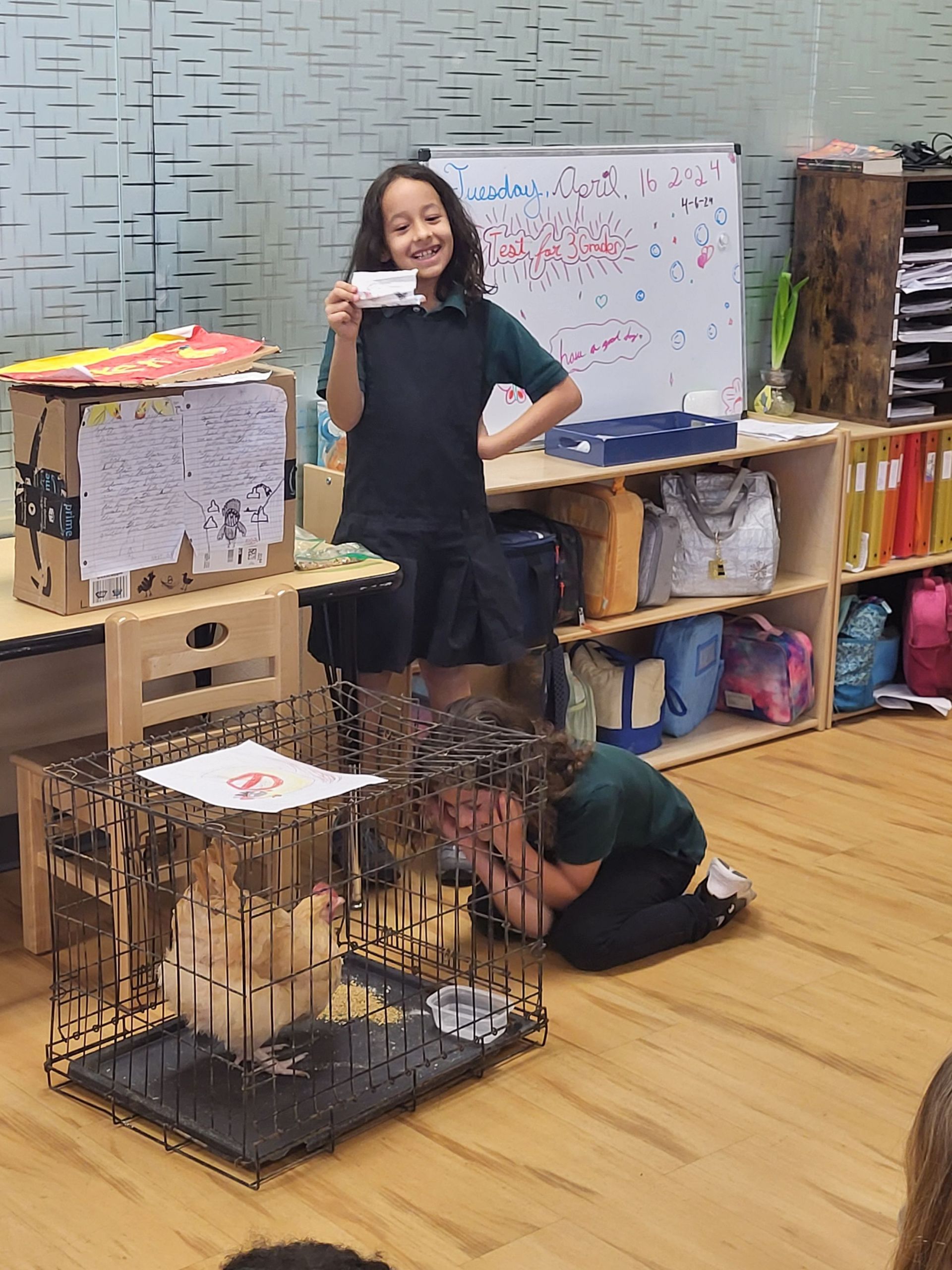

'Going out' in the Montessori classroom is not promoted by the teacher, but rather emerges as a response to the children's classroom activities, with a specific focus on their interests and responsibilities. Children typically work in small groups, engage in various projects, and when they recognize the need for external information beyond the classroom, the concept of 'going out' is born. It is essential to encourage children to explore their diverse interests. Children's own decisions propel these outings, whether driven by their unique interests or responsibilities within the classroom, such as restocking supplies or caring for classroom pets. The children themselves generate these explorations based on their chosen work and particular interests or needs. The possibilities for 'going out' destinations are thus boundless, which reflects the vast range of children's interests and curiosities.

'Going out' is a child-driven process where a small group, typically consisting of two to four children, organizes them. These groups spontaneously come together based on shared interests or common objectives, with no teacher intervention in group assignment. It is crucial to emphasize that children themselves are responsible for arranging the 'going out.' The teacher does not determine the details, such as the destination, timing, or logistics; instead, the children take on the planning and organizing tasks. The teacher's role is to offer guidance and support based on the children's prior experiences and age, without taking charge of the planning process. The goal is for the children to independently arrange these outings to the greatest extent possible.

Why have going outs?

In the elementary years, the child undergoes a significant developmental shift, characterized by heightened consciousness and a thirst for independence and knowledge. This phase is marked by a profound curiosity and a desire to understand the intricacies of the world.

The child looks for mental independence, seeking to explore the reasons and methods behind everything, while also developing a sensitivity to societal interactions. This growing child is inherently drawn to engage in organized group activities and collaborative projects. They begin to transcend the confines of the family and school, naturally gravitating towards the larger society. While not yet a fully mature individual, they are on the path to becoming an independent and responsible member of society. Recognizing this, it becomes evident that, both physically and mentally, the child between the ages of 6 and 12 requires broader horizons, and 'going out' serves as a vital response to meet these developmental needs.

What does the child achieve through going outs?

What we tell the children through going outs is: trust yourself, pursue your passions, and take the necessary steps to follow your heart. Your ideas and interests matter. You hold a valuable place in this world, and you have the power to make choices about where, when, and how you will journey. At first sight, going out can look like just a fun outing, but they are much more than just that. Making decisions without adults’ intervention allows them to:

- Prepare for life beyond family or school.

- Acquire bigger responsibility, independence and develop critical thinking.

- Experience human interdependencies and the exchange of services (when they go to the grocery store, they need to pay for what they need and the cashier will be there to help with that exchange).

- Appreciate and be grateful for others' work (when they go to the museum to learn more about a topic and a person helps them, the children develop a feeling of gratitude towards the person who is sharing their knowledge with them).

- Develop self-control and increase their self-esteem when they succeed in their going out and feel independent.

The going out allows the children to develop the skills necessary to live independently in society, or as Dr. Montessori says it, it makes “the spiritual being … capable of finding his way by himself” (From Childhood to Adolescence 13). One of the most valuable realizations for the child when they venture out is their capacity for responsibility in an expansive environment. When a child has a rich experience and fulfills their needs, they transition to adolescence with a solid foundation to continue their personal development.

Laura Ferrando

Upper Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published: November 2023

Community

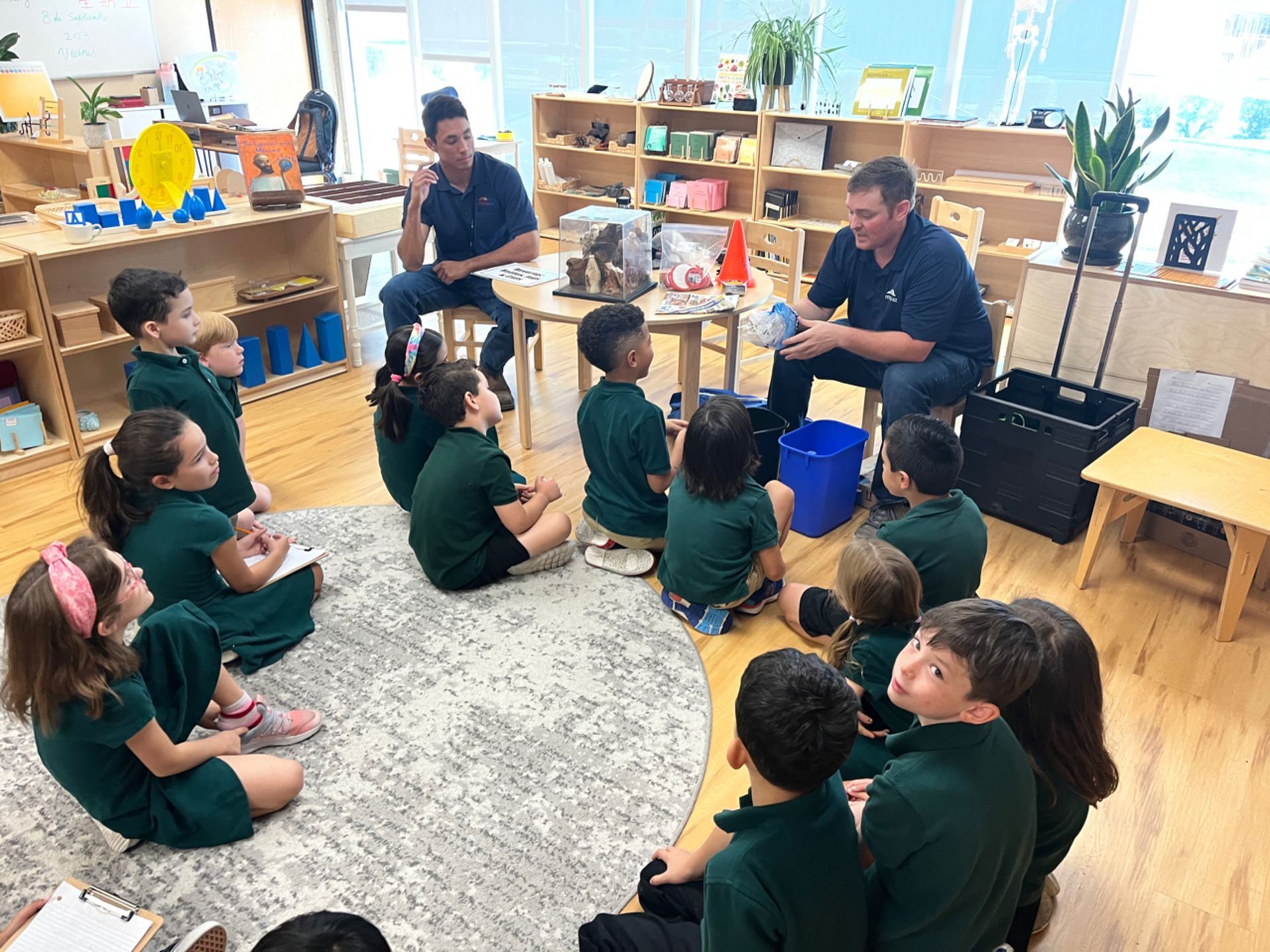

In the vibrant world of Montessori education, community is not merely a concept, it is a way of life that extends beyond the classroom walls. Dr. Montessori's educational philosophy places a strong emphasis on the interconnectedness of individuals, fostering a sense of unity and collaboration. This approach transcends traditional educational boundaries, encouraging a holistic understanding of community that encompasses both the microcosm of the classroom and the macrocosm of the world beyond.

Within the Montessori classroom, community-building is an integral part of the daily experience. Dr. Montessori recognized the importance of a supportive environment where children could learn not only from their teachers but also from one another. The multi-age classrooms promote a sense of family, with older children mentoring younger ones, creating a collaborative learning ecosystem. This structure not only enhances academic learning but also cultivates essential social skills, empathy, and a deep sense of responsibility toward one another.

The Montessori philosophy extends its reach to the home, considering the family as an indispensable component of a child's education. Collaboration between parents and teachers is not just encouraged; it's celebrated. Regular communication ensures that the principles of Montessori education seamlessly transition from the classroom to the home environment, creating a consistent and supportive learning experience. This partnership underscores the belief that education is a collaborative effort involving the child, the school, and the family.

Montessori education goes beyond the traditional curriculum by instilling a profound understanding and appreciation for diversity. Cultural studies are integrated into the curriculum, allowing children to explore and celebrate differences in traditions, customs, and languages. This intentional focus on learning about others fosters a global perspective and nurtures a generation of individuals who are not just academically proficient but also culturally competent and compassionate.

As Montessori students grow, they carry the values of community, collaboration, and cultural understanding into the wider world. The emphasis on practical life skills equips them with the ability to engage meaningfully with the community around them. Whether through service projects, community outreach, or environmental stewardship, Montessori education empowers students to be active contributors to society, emphasizing the importance of empathy and responsibility.

The Montessori approach to community-building is not just about the early years of education. It lays a foundation for a lifelong journey of learning, collaboration, and community engagement. The emphasis on self-directed learning and the ability to work harmoniously with others prepares Montessori graduates to thrive in diverse and dynamic environments, fostering a lifelong love for learning and a deep sense of responsibility to the global community.

In essence, the Montessori theory on community transcends the traditional boundaries of education. It creates a nurturing environment where children not only learn academic skills but also develop essential life skills and values. By fostering a sense of community within the classroom, extending it to the family, and instilling a deep understanding of and appreciation for others, Montessori education cultivates individuals who are not only well-prepared for the challenges of the future but are also compassionate, globally minded citizens.

Hattie Harris

Lower Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published: October 2023

Storytelling

Storytelling is a cornerstone of the Montessori education, especially in the Elementary years. Dr. Maria Montessori wrote, "The tales and stories which the child hears are meant to enlarge his imagination, stimulate his emotions, and enrich his conceptual powers." At the start of each school year, students are introduced to the Five Great Lessons - grand, impressionistic stories that categorize knowledge into five broad themes: The Coming of the Universe, The Coming of Life, The Coming of human beings, The Coming of Language, and The Coming of Numbers. These five great stories establish the framework of Cosmic Education, providing a meaningful context to explore academic subjects and the interconnections of life.

The Great Stories spark children's imaginations and curiosity about cosmic Education. As Dr. Montessori explained, "The vision of the universe which we wish to give the child is one of majesty, and order, of law, of wonder, and of beauty." The stories do not focus on minute details that may limit a child's conception of possibility. Rather, they paint an inspiring vista leaving room for the child's imagination and questioning. Stories thus motivate self-directed exploration of astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology, and more. Children are compelled to collaborate to piece together the great mysteries of our cosmos.

Beyond the Five Great Lessons, storytelling continues throughout the years. Myths, fables, historical narratives - stories are woven through nearly every subject. We tell the story of early mathematicians developing numerical systems and pioneering geometric principles. Students connect emotionally to the triumph and struggle of history. Stories reveal the interdependence of humanity - how we rely on farmers, builders, inventors, and artists from the past and present. Dr. Montessori wrote, "Man needs to enter into relationship with the universe; he needs to feel himself at one with other living creatures, with rocks, flowers, sunlight, and stars." Stories bind us together.

James Qiao

Lower Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published: September 2023

Freedom and Responsibility

“The first task is to shake life, but leave it free to develop”

- Maria Montessori

One of the fundamental principles in a Montessori environment is freedom. Freedom is understood as the freedom to choose your work, your workplace, your coworkers; freedom of movement, freedom of thought, and freedom of expression and communication. However, for this freedom to exist, limits are necessary. Common limits which are based on respect for the environment, materials, classmates, and the children themselves. These limits allow the child's freedom. Boundaries must be respected to maintain this freedom, hence the responsibility. Children should use their freedom responsibly.

Freedom is the capacity for self-determination of the will, which is knowing what one wants and where one is going. It is also knowing that decisions have consequences.

Children construct their own learning, taking into account their interests and therefore it is common in Montessori environments to find children working with different materials and exploring different areas of learning. Each of these children has chosen their own work. Not just any type of work, but productive work. This is the first act of responsibility that must be observed in the environment. Is the child choosing their work appropriately? Are they using their freedom responsibly?

Let's look at two examples:

Example 1:

“M.F. chose to start the day by calculating the common factors between two numbers. At 8:35 he sat down at his workplace and started working. At 9:05 he decided to stop his task to have a small snack. At 9:13 he resumed his work. At 9:30 he finished his work. During this time he solved 20 problems.”

Example 2:

“S.T. chose to start the day with her research work on spiders. At 8:46 she sat down at her workplace and started working. At 9:02 she decided to stop her task to have a small snack. At 9:10 she walked around the area. She returned to her workplace at 9:30. At 10:47 she finished her task. During this time she wrote 3 lines.”

These two examples are situations that are observed daily in the environment. The two children had the opportunity to choose their work, they themselves decided what to do. Nobody told them anything or directed them. Obviously one of the two is not using their freedom responsibly, not because they don't want to, but because they are not yet ready for it. The work of one of the two has not been productive. This is where an intervention must be made, limiting this freedom until the child is ready to use it consciously.

However, interventions should not be arbitrary or authoritarian, but rational. At this stage of development, children are developing their reasoning mind and can understand such a limitation if it is explained to them appropriately. For this, weekly individual meetings with the children are essential. In these meetings, the child's weekly activity is assessed. The child records his work daily in a record book. This tool helps both the child and the guide to recognize productive work. It is here, during this meeting, that the limitation of the child's freedom of choice of work is assessed as necessary.

Similarly, freedom of movement must also be observed. Children can move freely around the environment. This means not just getting up to drink water, go to the bathroom, or stop to have a snack, but also to change your workplace whenever you need to. They can start the day working outside, or near the art area, and end it working on the floor or on the experiment table. During the day the flow is enormous. Once again, the observation of the guide is essential. During this time of movement, unless the child’s own integrity or that of her companions is endangered, the guide does not intervene, she only observes. It is during the meeting with the child, with the support of the record book, that it will be assessed whether this freedom of movement was used responsibly or, on the contrary, it was affecting their concentration and productivity. If the latter is the case, the freedom will be temporarily limited by the guide making the work choices for the child.

Communication is an aspect that is promoted in the environment, giving children the opportunity to do group work. During this work, children exchange opinions, share ideas, and make decisions together. Therefore, they decide who to work with. Again, observation is the key.

Let's look at two examples:

Example 1:

“At 9:32 T. and H. are working on a project about the chinchilla. They go outside to paint a poster and make a model of the habitat of this animal. During this time they are observed concentrating and talking about work. At 10:45, S.W., who was working inside the environment, approaches with interest and curiosity and asks about the project. In the end, S.W. decides to help them in the investigation. They continue working until 11:30, when it is time to clean up."

Example 2:

“At 9:32, T. and H. are working on a project about the chinchilla. They go outside to paint a poster and make a model of this animal's habitat. During this time they are observed concentrating and talking about work. At 10:45 a.m., L.L. , who was inside the environment, approaches and catches their attention. L.L. is doing something silly and the other two children laugh. They are seen playing and talking about topics unrelated to work. At 11:30 it is clean up time.”

These two examples are situations that are observed daily in the environment. S.W. and L.L. had freedom of movement and communication. They voluntarily decided to go outside to talk to their companions. However, in one of the two situations, a responsible use of freedom of communication was not observed. Not only was the conversation not about the work at hand, but the concentration of others had also been interrupted. This is where an intervention must be made, limiting this freedom until the child is ready to use it consciously. This fact will be discussed again in the individual meeting with the child.

Finally, freedom of thought, being able to think without being judged, is essential. How else could decisions be made? When a child makes a decision, he does nothing other than execute a thought. This thought should never be judged without first observing the result. It is common in the environment for children to choose a follow up work to practice a lesson. Each child knows what they need for this. No choice should be taken lightly.

For example:

“After receiving a lesson about the parts of the mountain, C.L has decided to bake a cake in the shape of a mountain and point out its parts. Other classmates have helped. Later this work of the mountain was shared with the classroom community. The result was a sweet follow up work that everyone enjoyed”

Another example:

“After receiving a lesson on the diagonals of a polygon, L.R. has decided to make a poster with different polygon designs. They chose to work alone. After 2 hours only 3 designs were drawn. The child did not point out the diagonals. This results in unfinished work that ends up in the poster basket. No presentation to the community is expected. ”

In both cases the child's freedom of thought has been respected. No one has told them which follow up work was better, nor has their choice been judged during its execution. It is only when seeing the result that it is possible to assess whether the decision made was responsible, and, again, this aspect will be discussed in the meeting with the child.

In conclusion, as Maria Montessori pointed out, the child must be allowed to work freely, accompanied with reasonable limits until they are prepared to use that freedom responsibly.

Silvia Fortuny

Upper Elementary Guide

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Published: August 2023

Cosmic Education

The Montessori Method of education was established by Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and scientist, as an aid to life. She recognized the need for a different type of education, one that was based on the developmental needs of children and saw the inherent power of the child to create the person they were to become. This was, and continues to be, a revolutionary method of education, which takes into account the whole child and allows each individual being to actualize their unique potential.

In the Elementary classrooms, we provide “Cosmic Education”. According to Webster’s dictionary, “Cosmic” means “of or relating to the universe” and “Education” means the “acquisition of knowledge or skills”. In its most basic sense, Cosmic Education is a way of educating in context to the universe; a way of seeing the inter-relatedness of all that is within the universe.

“Cosmic education is a way to show the child how everything in the universe is interrelated and interdependent, no matter whether it is the smallest molecule, or the largest organism ever created. Every single thing has a part to play, a contribution to make to the maintenance of harmony in the whole. To understand this network of relationships, the child finds that he or she also is a part of the whole and has a part to play, a contribution to make.”- Phyllis Pottish-Lewis

How do we present Cosmic Education? We could give facts and figures that need to be memorized, but this would not serve the children who are entrusted to us. Dr. Montessori said, “The secret of good teaching is to regard the child's intelligence as a fertile field in which seeds may be sown, to grow under the heat of flaming imagination. Our aim therefore is not only to make the child understand, and still less to force him to memorize, but so to touch his imagination as to enthuse him to his innermost core.” So, that is what we do!

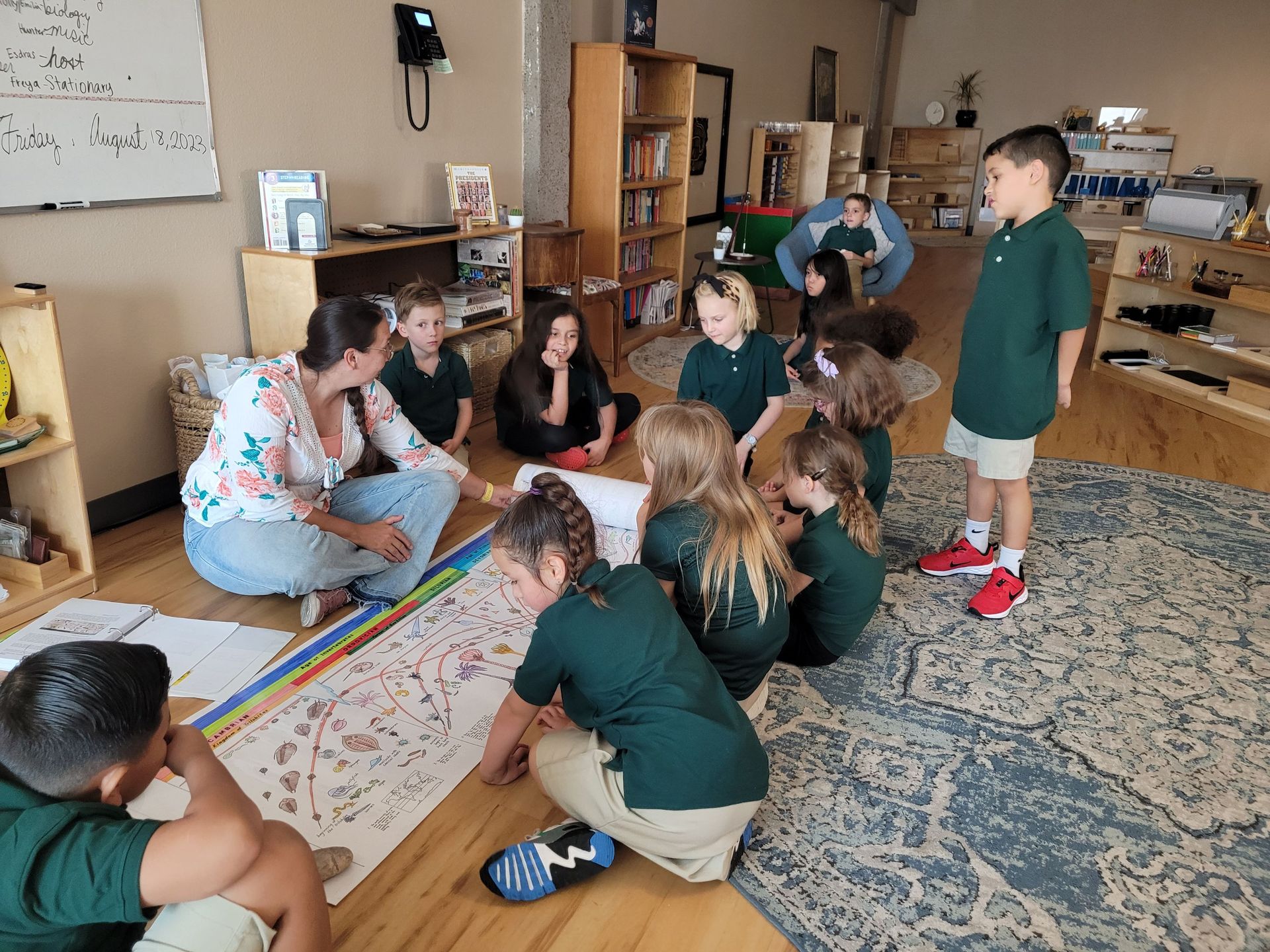

This form of education is based on understanding the universal Human Needs and Tendencies and the Psychological Characteristics of the 2nd Plane of Development (ages 6 – 12 years). Elementary children have reasoning minds and great imaginations. They want to know the “why” behind facts. We take advantage of these two characteristics, the reasoning mind and active imagination, to “sow the seeds” by giving Montessori’s “Great Lessons”. These lessons are elaborate stories told with great majesty and grandeur to introduce the children to Geography, Biology, History, Language, Mathematics, Art, and Music. These Great Lessons give the children a clear picture of how our universe was created, furnished, developed, and built to be as it is today for us to enjoy.

The first Great Lesson, The Formation of the Universe, talks about the creation of the universe. Children learn about the composition of the Earth being that of Solid, Liquid, and Gas, and how these elements each have laws and principles that govern them, and that they work in harmony according to these principles to create the perfect balance in the universe.

The second Great Lesson, The Coming of Life, introduces life onto our earth. Children see that plants and animals furnished our earth with all that was needed for the survival of the human being.

The third Great Lesson, The Coming of Human Beings, heralds the arrival of humans on the earth, emphasizing how the timing of his arrival onto the earth was perfect, for if humans had arrived at any other time, their survival could not have been guaranteed.

The Fourth Great Lesson, Communication in Signs, illustrates the development of written language from crude drawing to the development of the alphabet as it is today.

The fifth Great Lesson, The Story of Numbers, introduces the language of numbers to the children. The children see the early human’s need to count and keep track of the world. How, with inventions and creations, came the need for Mathematics and Geometry.

These Great Stories open up the Elementary curriculum to the children. As lessons in all the areas continue, children begin to see and understand how they fit into this grand cosmic plan. What is their responsibility? How do they fit? Do they have a contribution to make?

Maria Montessori said that the child is the agent of change, our hope for the future. With Cosmic Education, we have an opportunity to instill a sense of awe, wonder, and responsibility in the children with the hopes that they will then be able to find their unique and special path in the world.

Shahnaz Currim

Elementary Program Director

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Heartwood Montessori - All Rights Reserved