ELEMENTARY ARTICLES

Published: March 2025

How Group Work Improves Learning and Social Skills

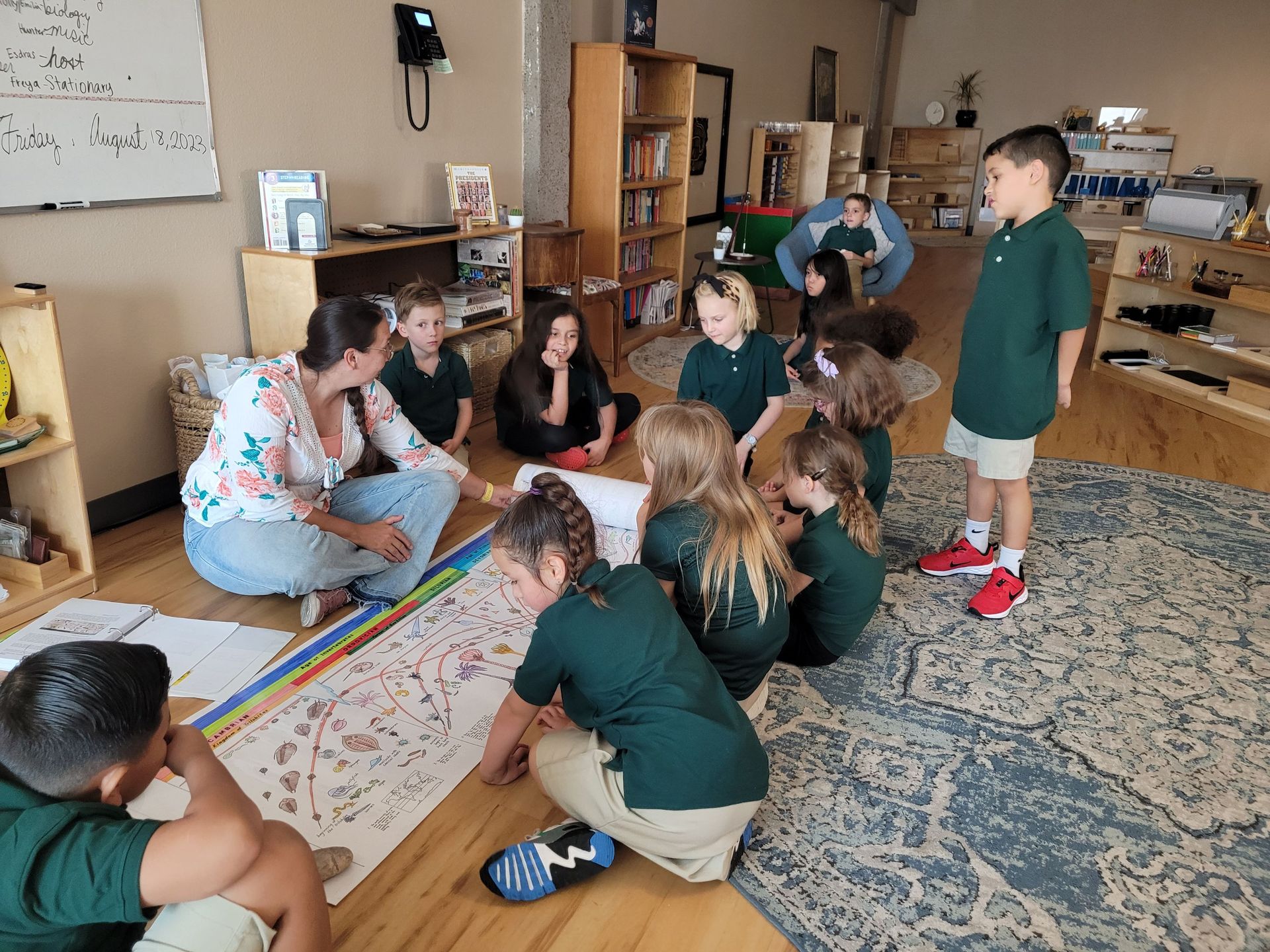

Group work is one of the defining characteristics of a Montessori environment. In an elementary classroom, group work is not just encouraged, it is essential. Dr. Maria Montessori observed that children learn best from and with each other, in her words, "The best teachers for children are children themselves."

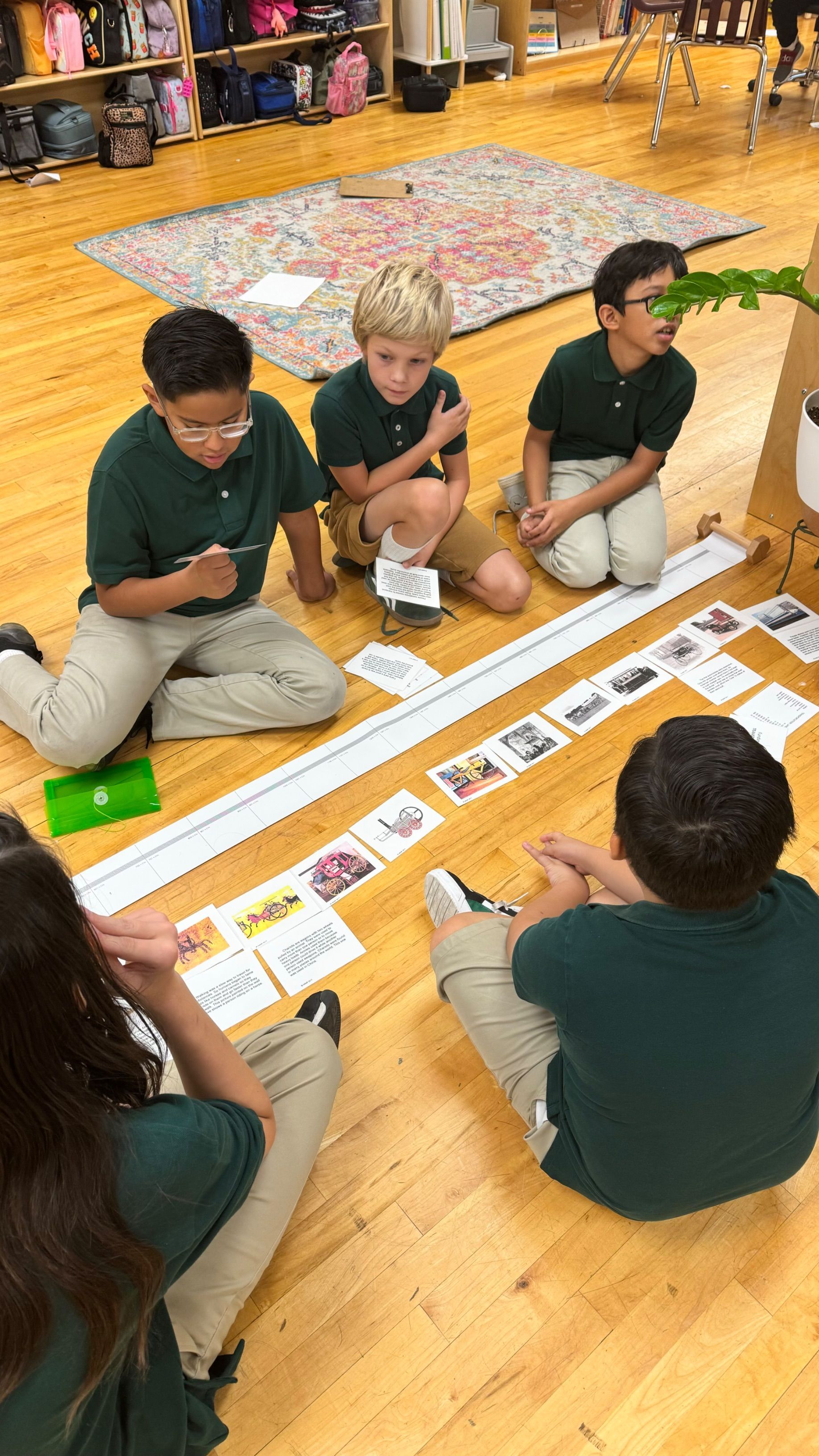

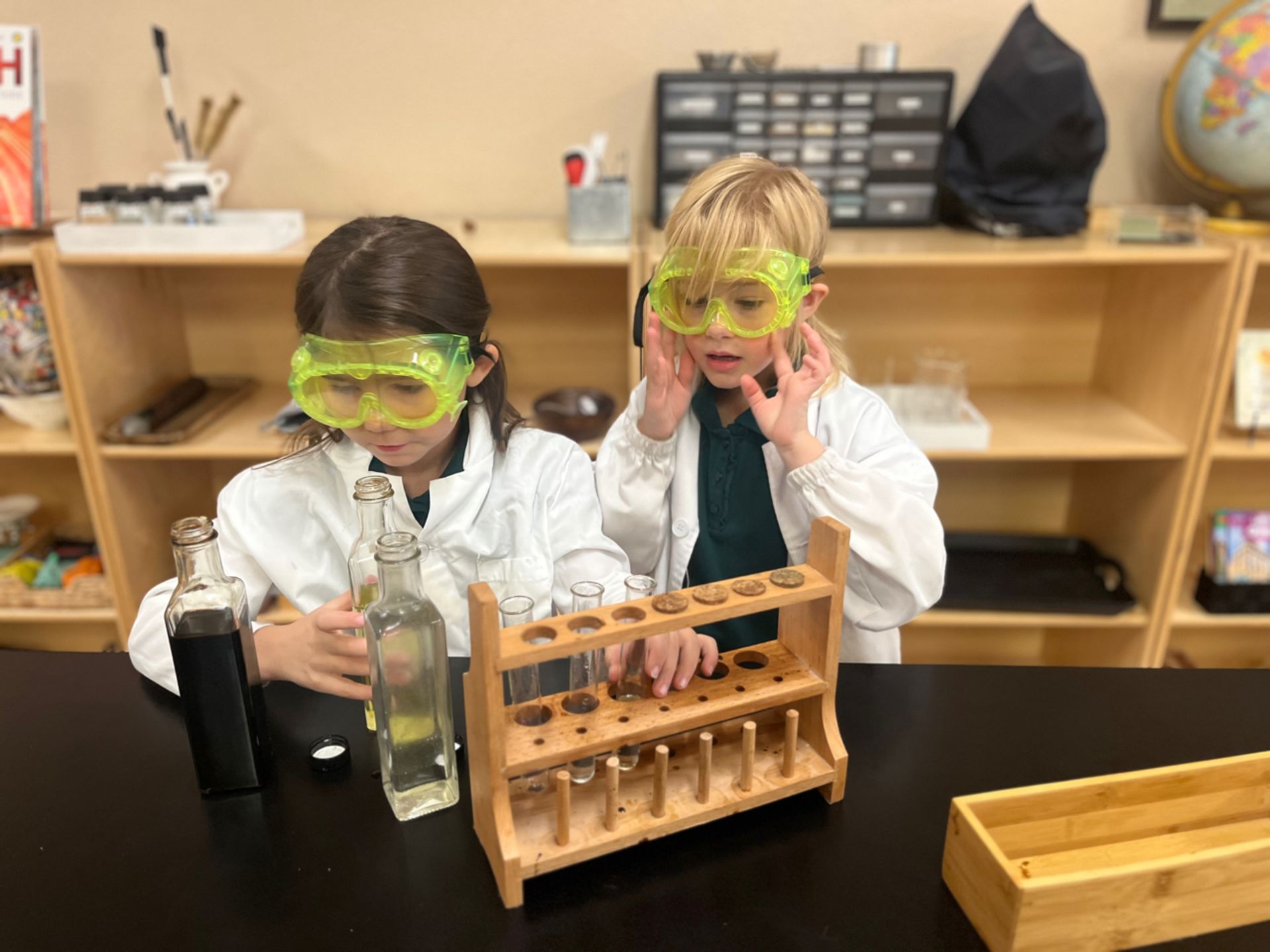

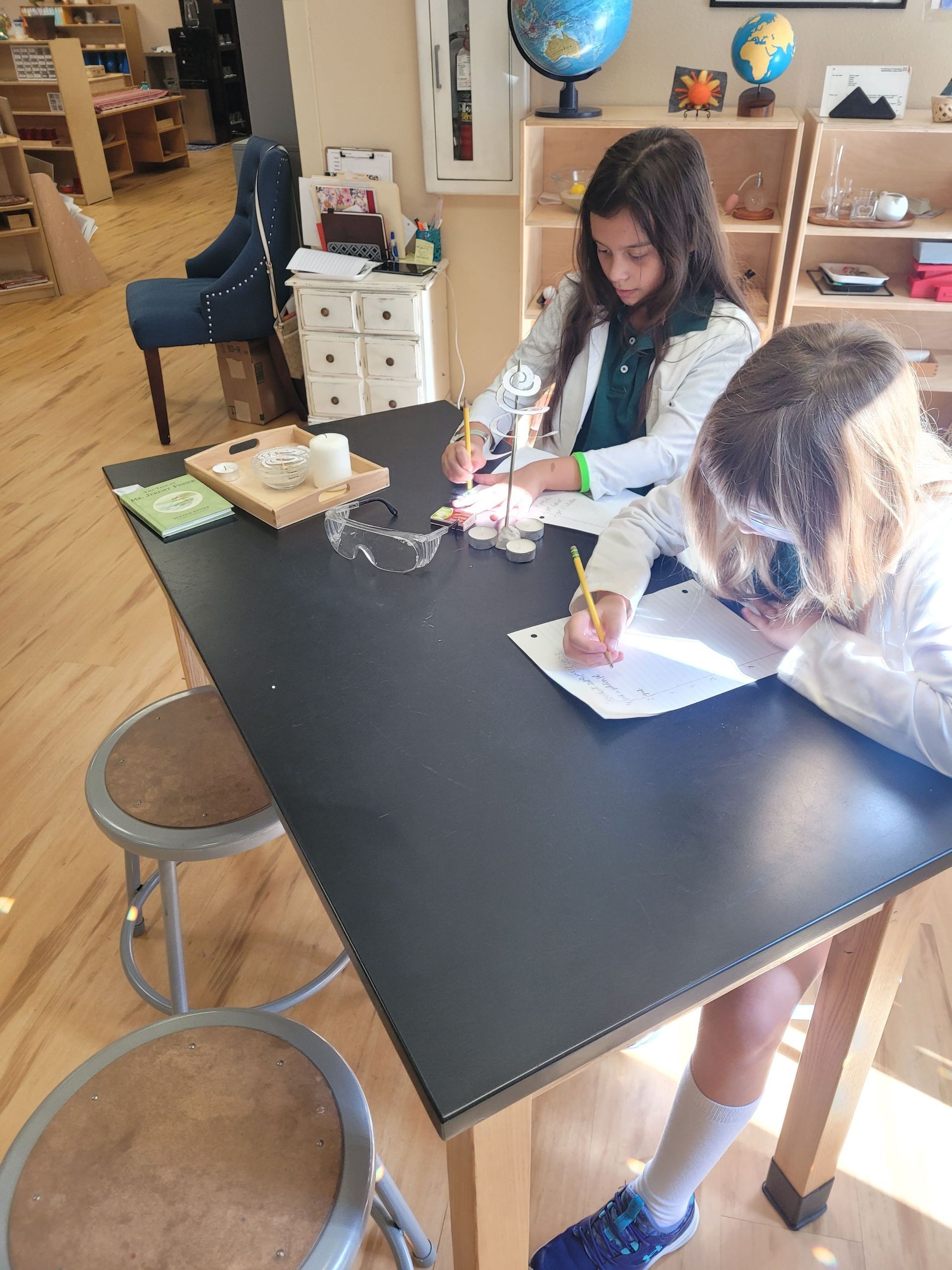

Children in the second plane of development (ages 6-12) are highly social, drawn to collaboration and peer interaction. That is why at these ages they form strong friendships and prefer working together. Another characteristic of the second plane is their reasoning mind, they ask deep questions, analyze information critically, and develop a strong sense of justice and fairness. Also, their imagination expands, allowing them to explore abstract concepts. As a guide, I can see this every day, whether it’s in a debate over history, a science experiment, or a group storytelling activity. Maria Montessori observed this need of the child, and for this reason, all the lessons in the elementary class are done in small groups, encouraging discussions and group projects that challenge their intellect and social development.

Montessori classrooms are age-mixed environments. This structure allows older students to step into leadership roles, guiding and assisting younger students. The process benefits both: the younger children receive peer instruction that is often more relatable, while the older students reinforce their own knowledge through teaching. This reciprocal learning fosters confidence, patience, and a deeper understanding of the materials.

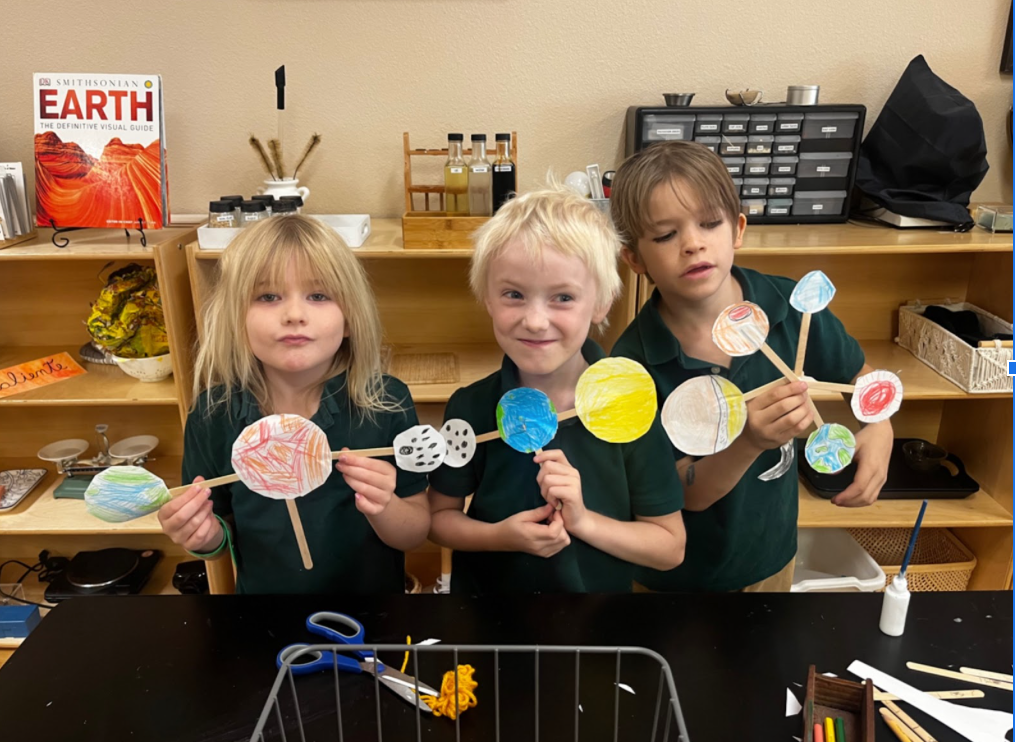

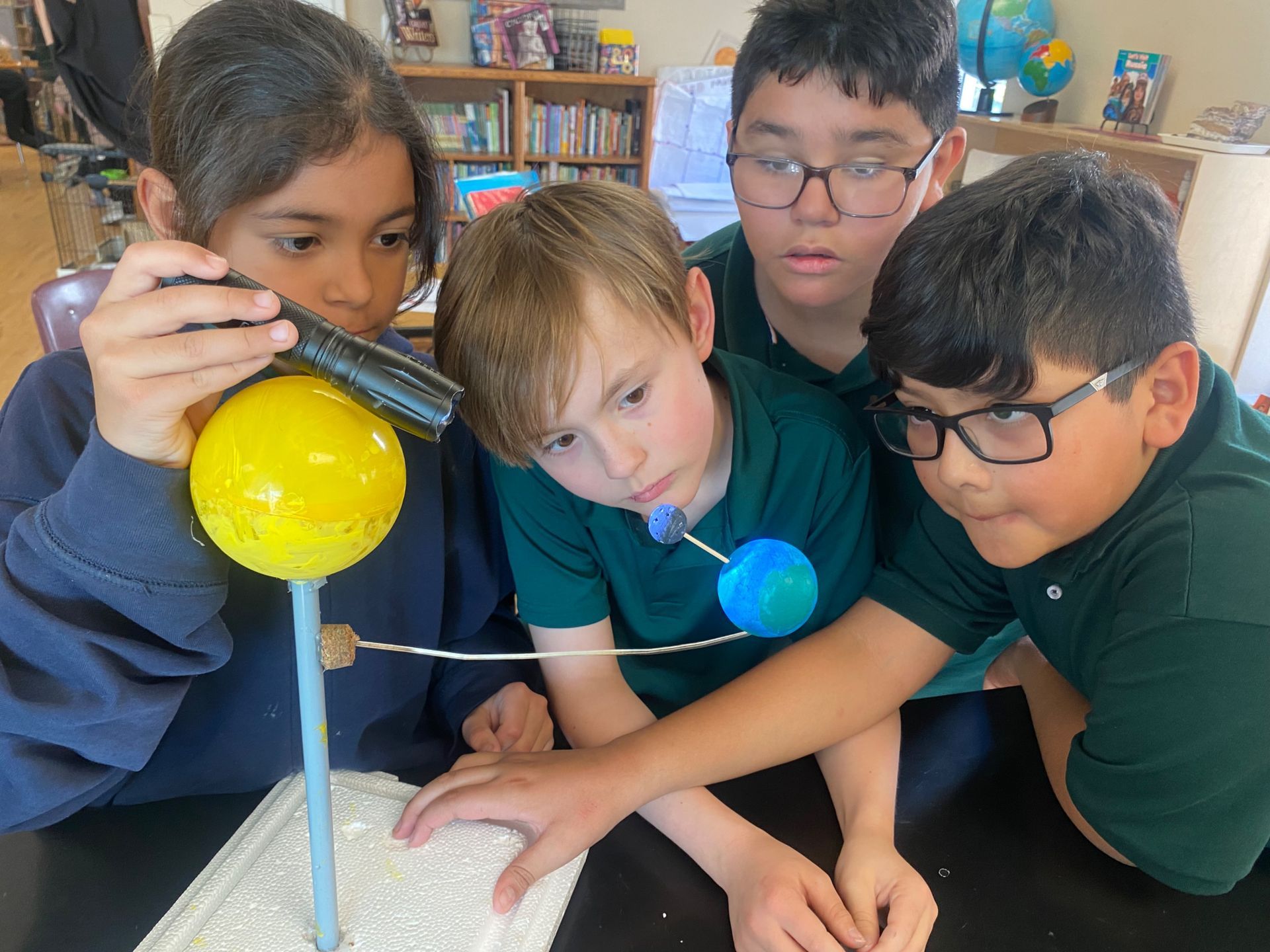

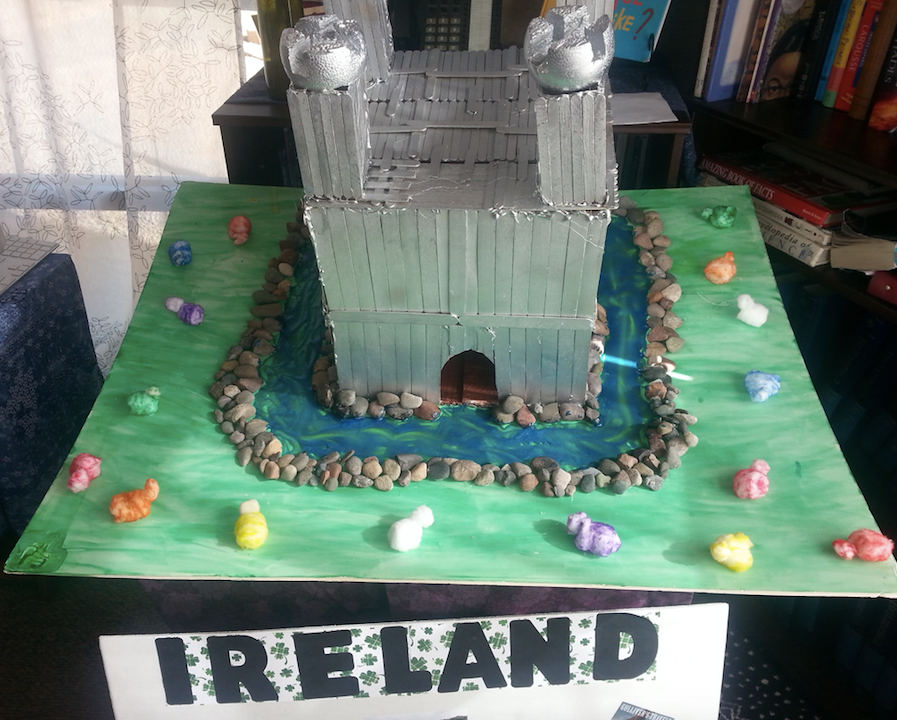

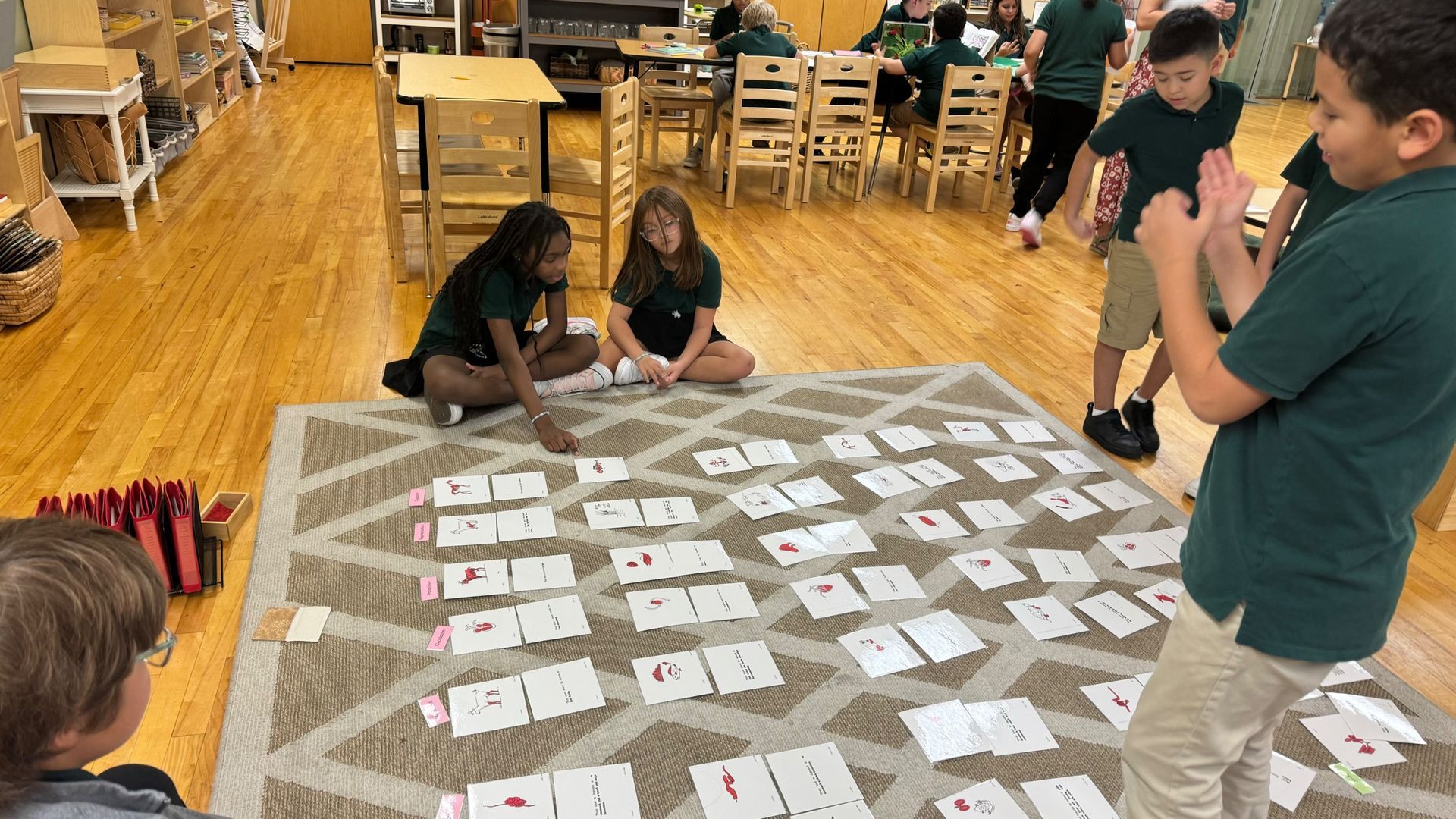

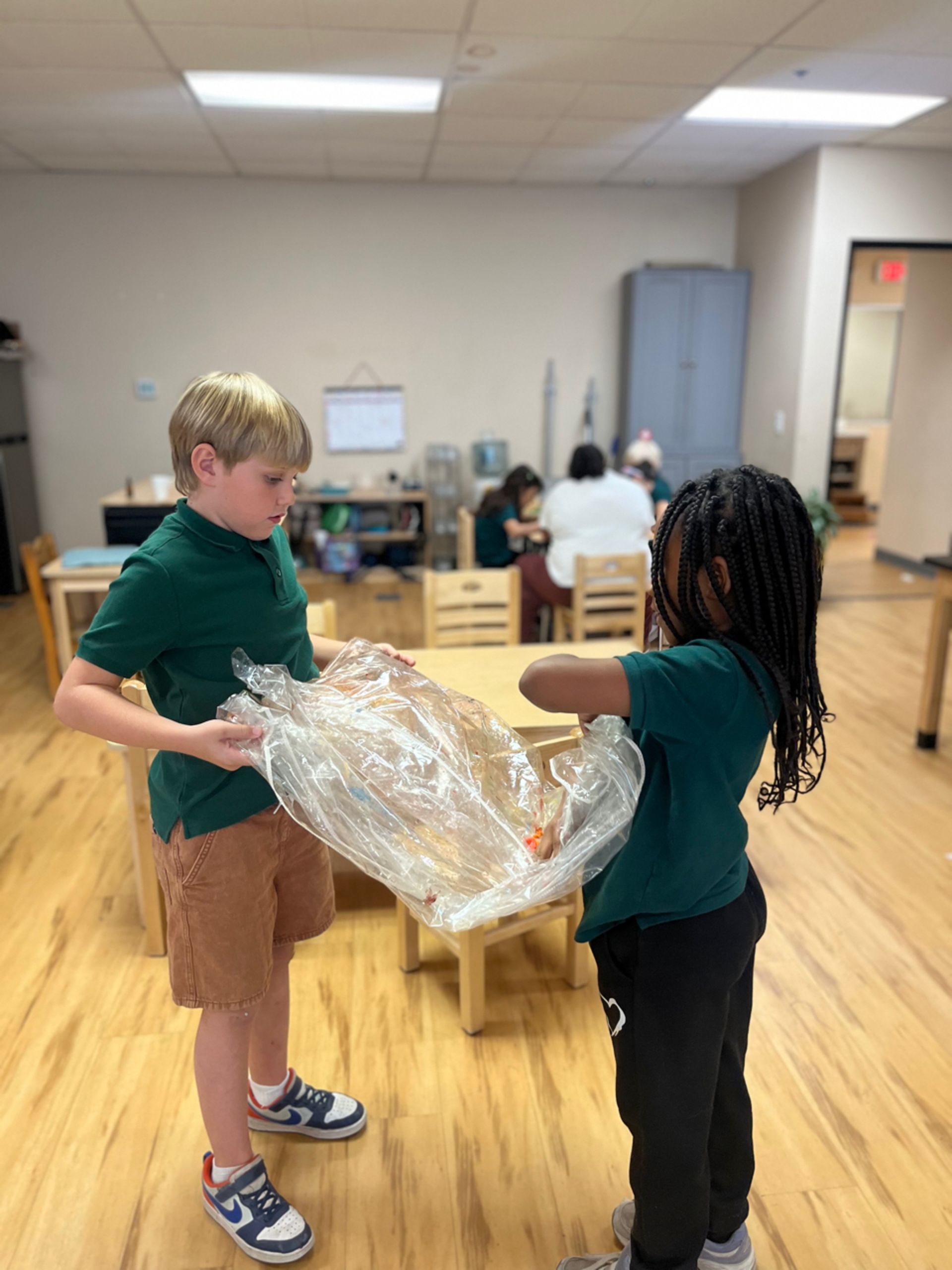

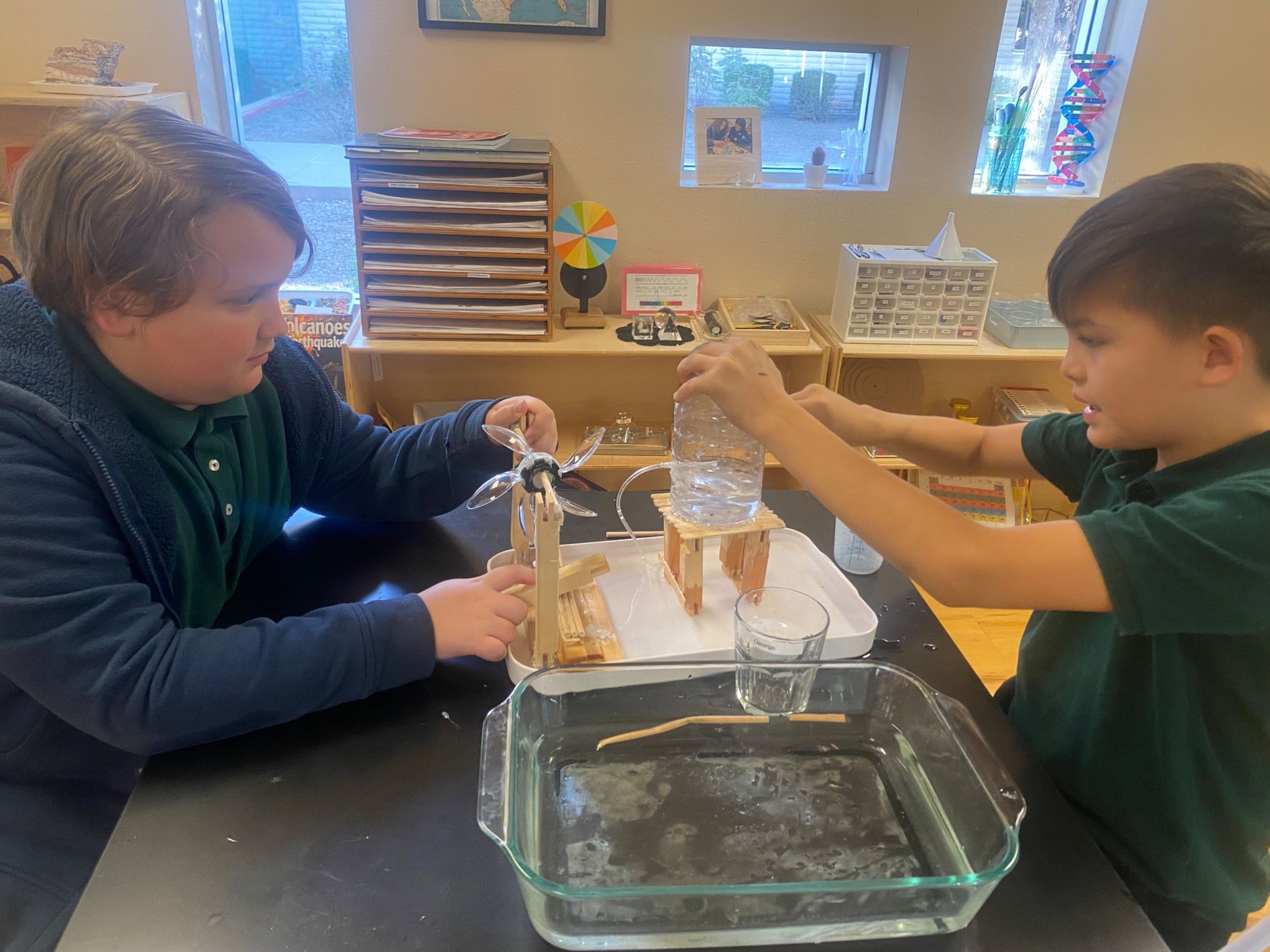

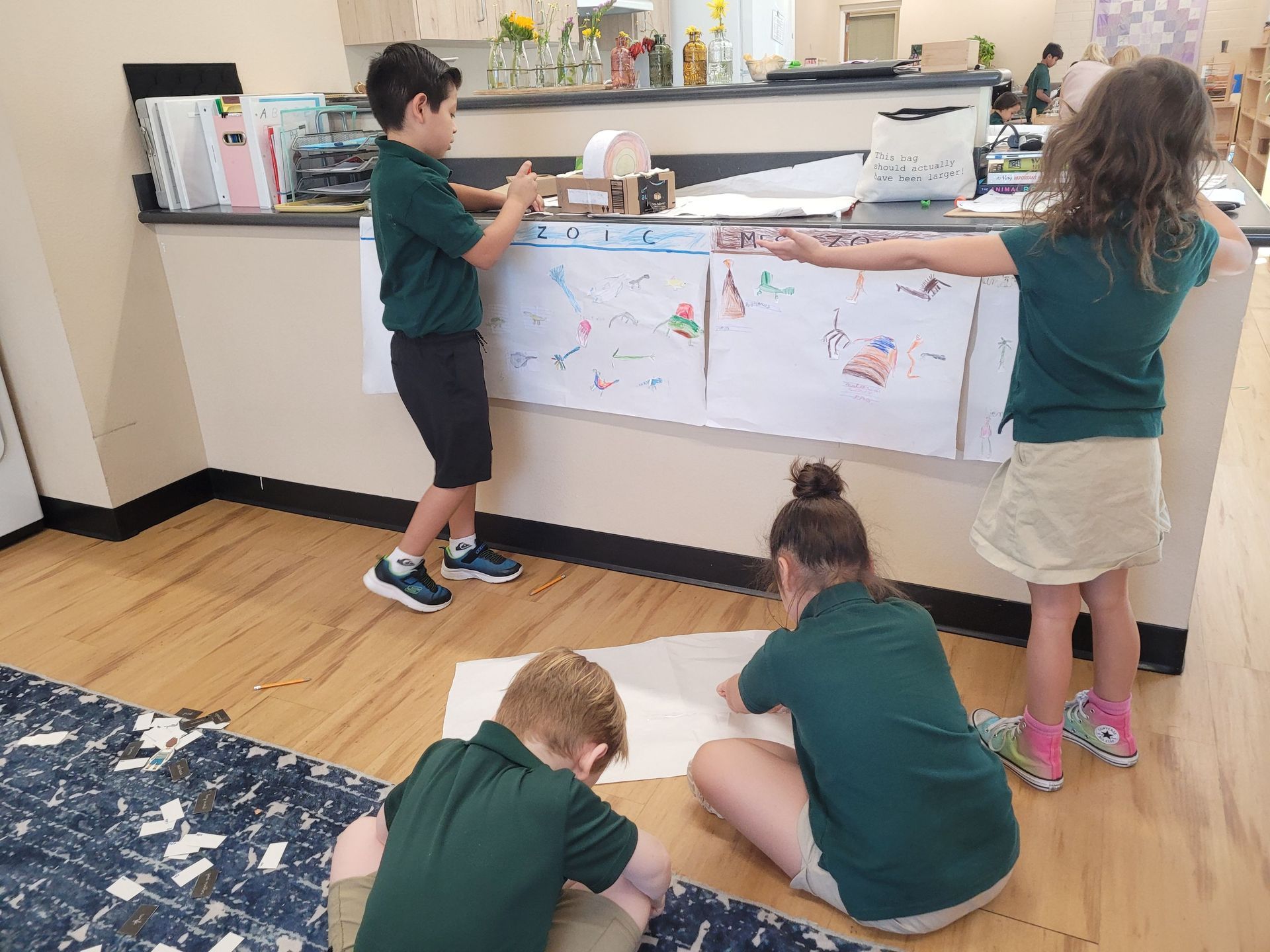

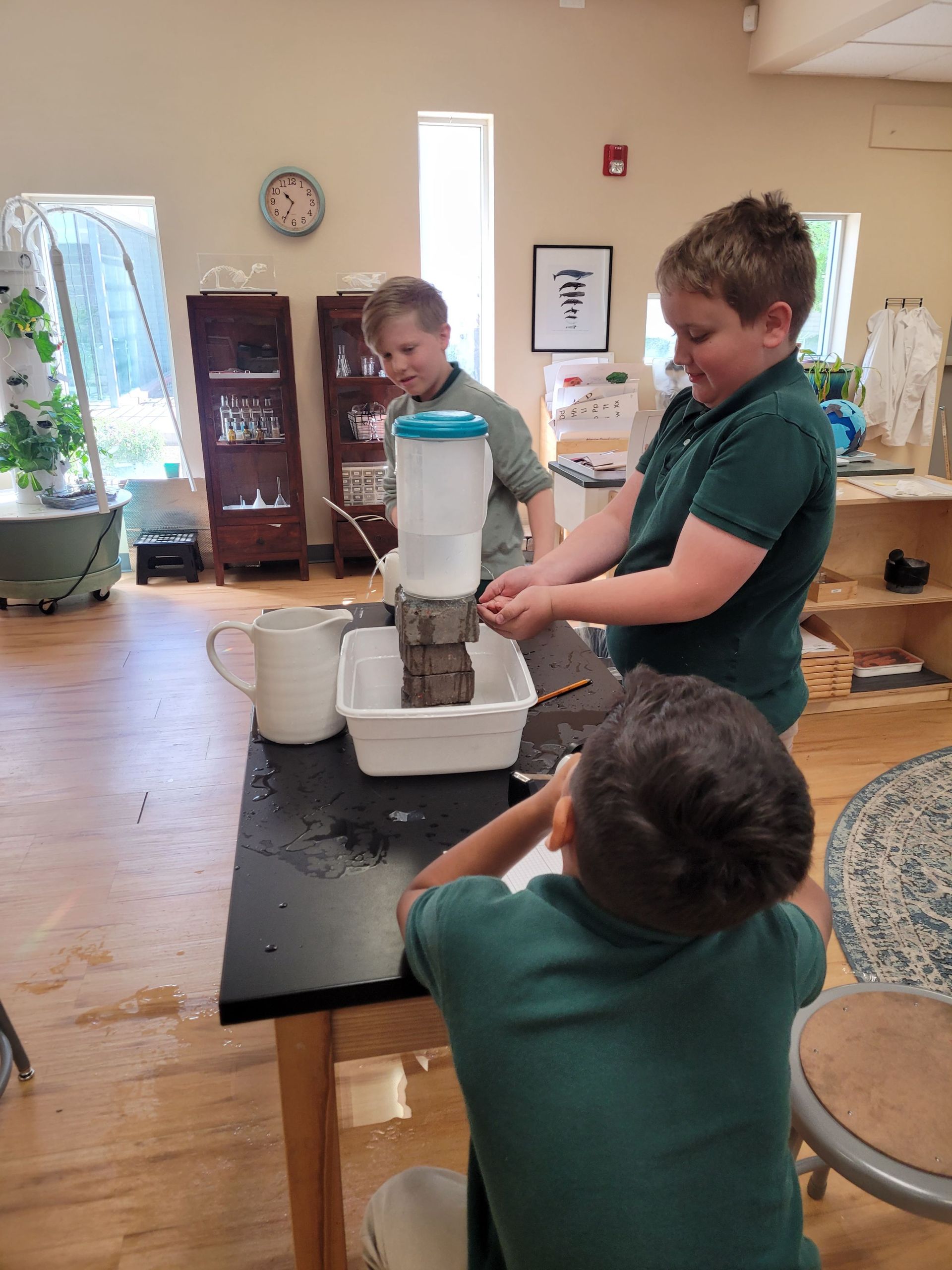

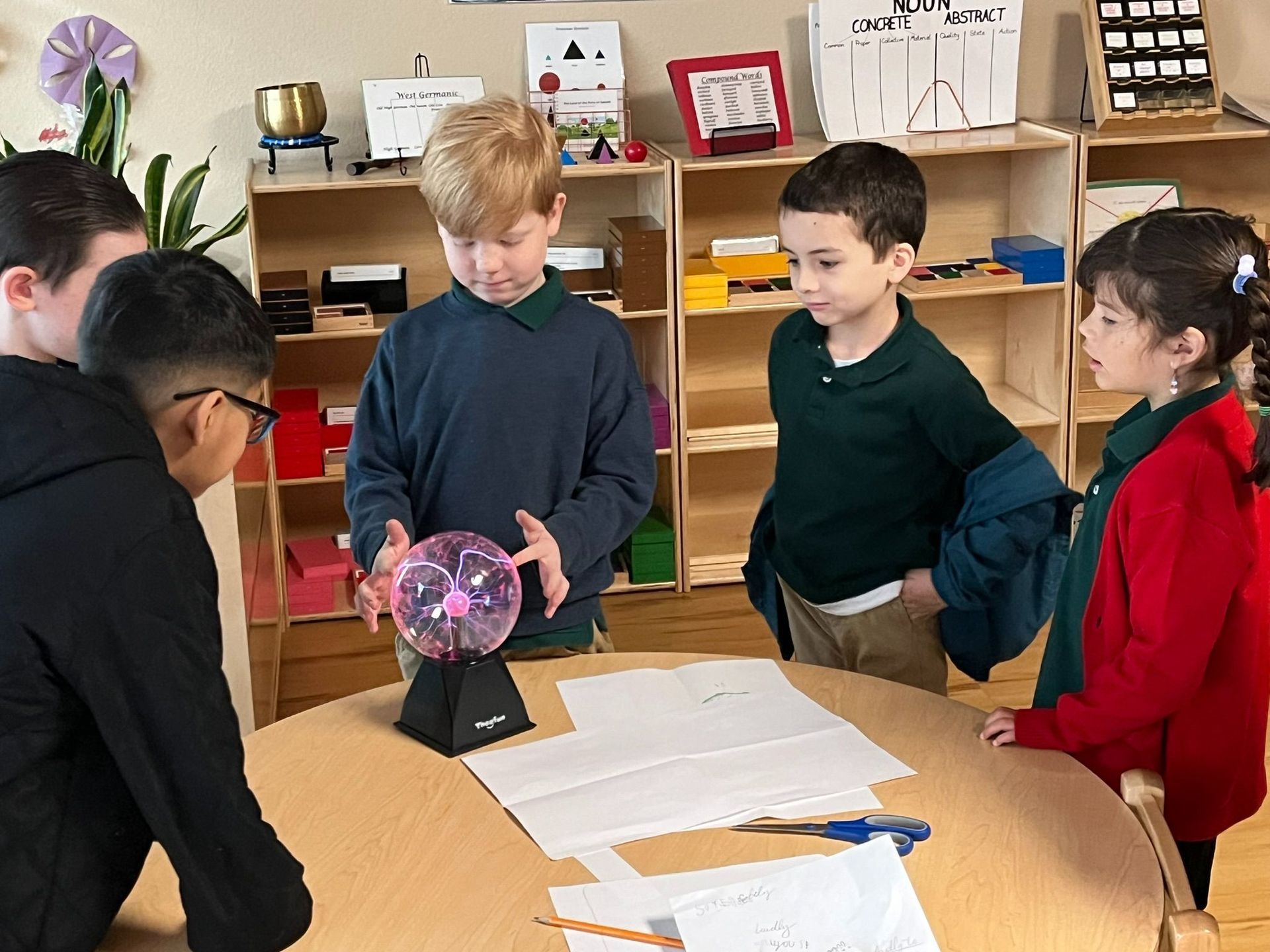

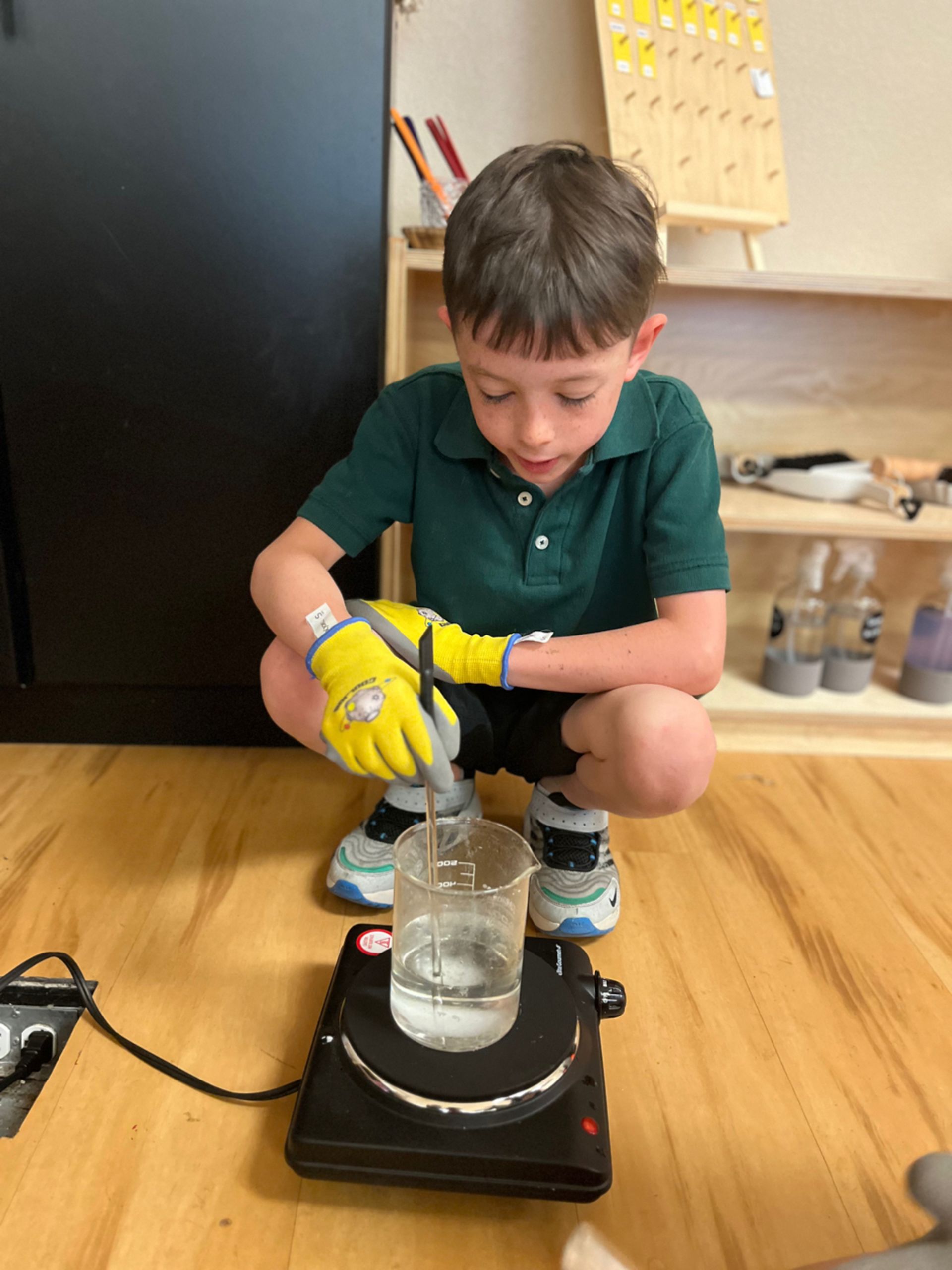

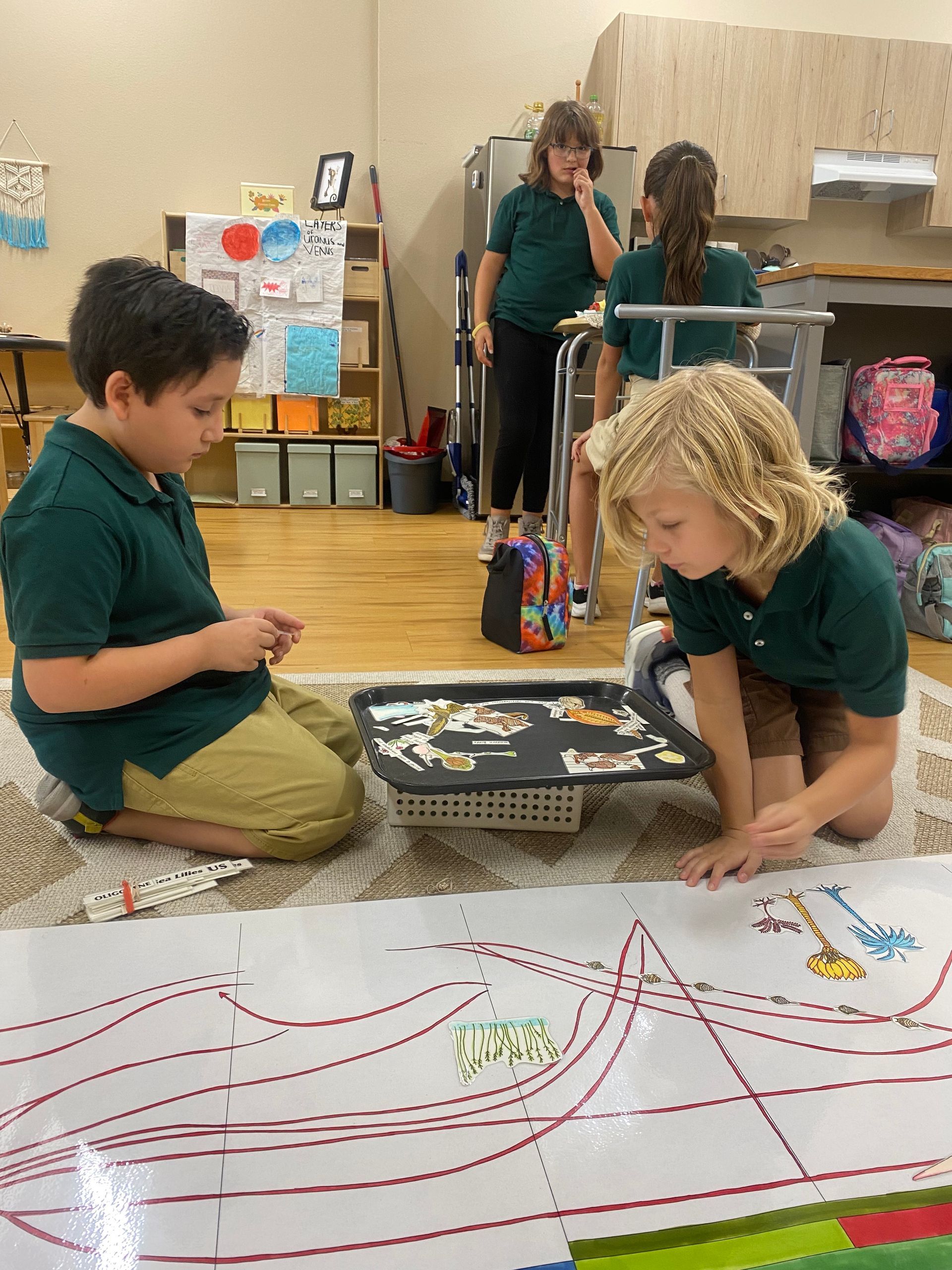

Group work occurs when students collaborate on one project, producing a single shared result. They must communicate, divide tasks, and reach a consensus. The power of group work can be seen in so many different projects. For example, some of my students worked together to build a huge model of the water cycle. They labeled the different elements and showed the processes of evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. I remember how excited they were when building their model. Another group also worked on building a model of a river in the garden area, simulating erosion (with the hose) to show how water can shape our planet over time. Watching them problem-solve was a testament to the power of group work.

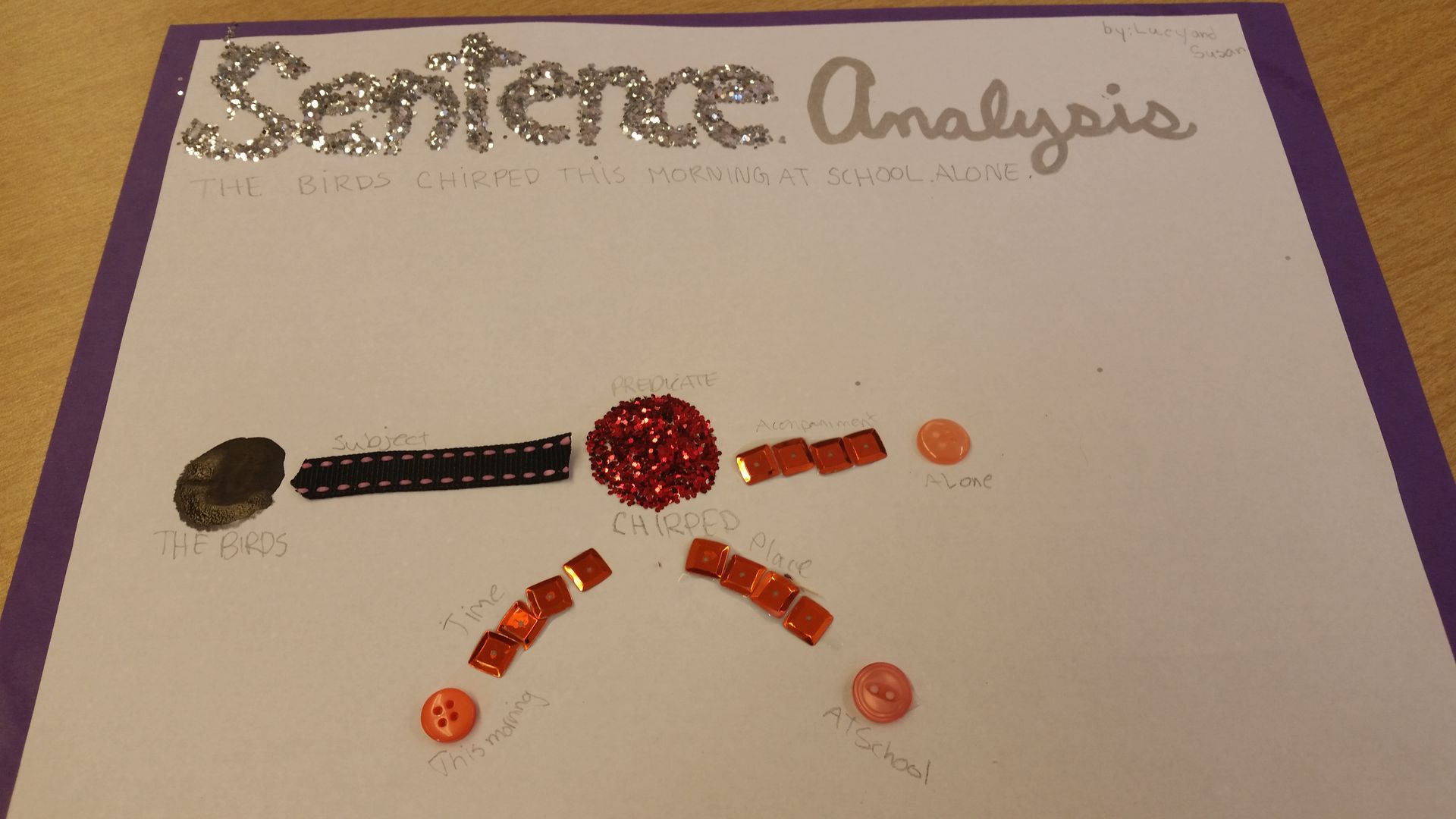

Any subject can benefit from collaborative projects, a key aspect of Montessori's cosmic education. Cosmic education means that subjects are interconnected rather than isolated, hence children can apply their understanding of grammar to a creative project. For example, to better understand transitive and intransitive verbs, a group of students came up with a puppet show. They made their own puppets and built a small stage. Through their performance, they brought grammar concepts to life, making the lesson memorable and meaningful. I still smile when I think about the creativity in their scripts and the enthusiasm with which they performed for their classmates.

Benefits of Group Work

Group work teaches students critical life skills, such as:

- Listening to others’ perspectives

- Expressing their own ideas clearly

- Negotiating and compromising

- Resolving conflicts constructively

These skills prepare them for real world interactions. Montessori education is an aid to life, it focuses not just on academics but takes a holistic approach that nurtures the personal growth of the child. Through collaboration, children develop independence, emotional intelligence, and responsibility.

Group work fosters moral development as well. In the words of Maria Montesssori: "We must help the child act for himself, will for himself, think for himself; this is the art of those who aspire to serve the spirit." And let’s be honest, sometimes it also fosters deep patience too, when students negotiate who gets to use the markers first! When students work together, disagreements are inevitable. They must learn to express their thoughts, defend their opinions, and sometimes concede for the sake of the group’s success. These discussions are really valuable.

In conclusion, during group work, children learn how to function as part of a team, communicate effectively, and solve problems. These skills will serve them not only in school but throughout their lives. So, next time you hear about a lively discussion in the classroom, know that real learning is taking place!

Laura Ferrando

Lead Upper Elementary Guide

Published: February 2025

Research: A Way to Discover the World

When children are in Primary, they are handed the keys to the world around them. It marks the beginning of their journey to understanding the names and functions of everything they encounter. They begin to explore a fascinating and complex society, using all of their senses. They want to touch, explore, name, listen, and move. Their eyes light up with curiosity as they start to classify the world — from colors and shapes to sounds and textures.

But what happens when they transition to Elementary? What are they searching for now? Maria Montessori, through her careful observations of children between the ages of 6 and 12, discovered that their minds undergo a profound transformation.

“We are confronted with a considerable development of consciousness that has already taken place, but now that consciousness is thrown outward with a special direction, intelligence becoming extroverted, and there is an unusual demand on the part of the child to know the reasons for things.” (Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential, p.3)

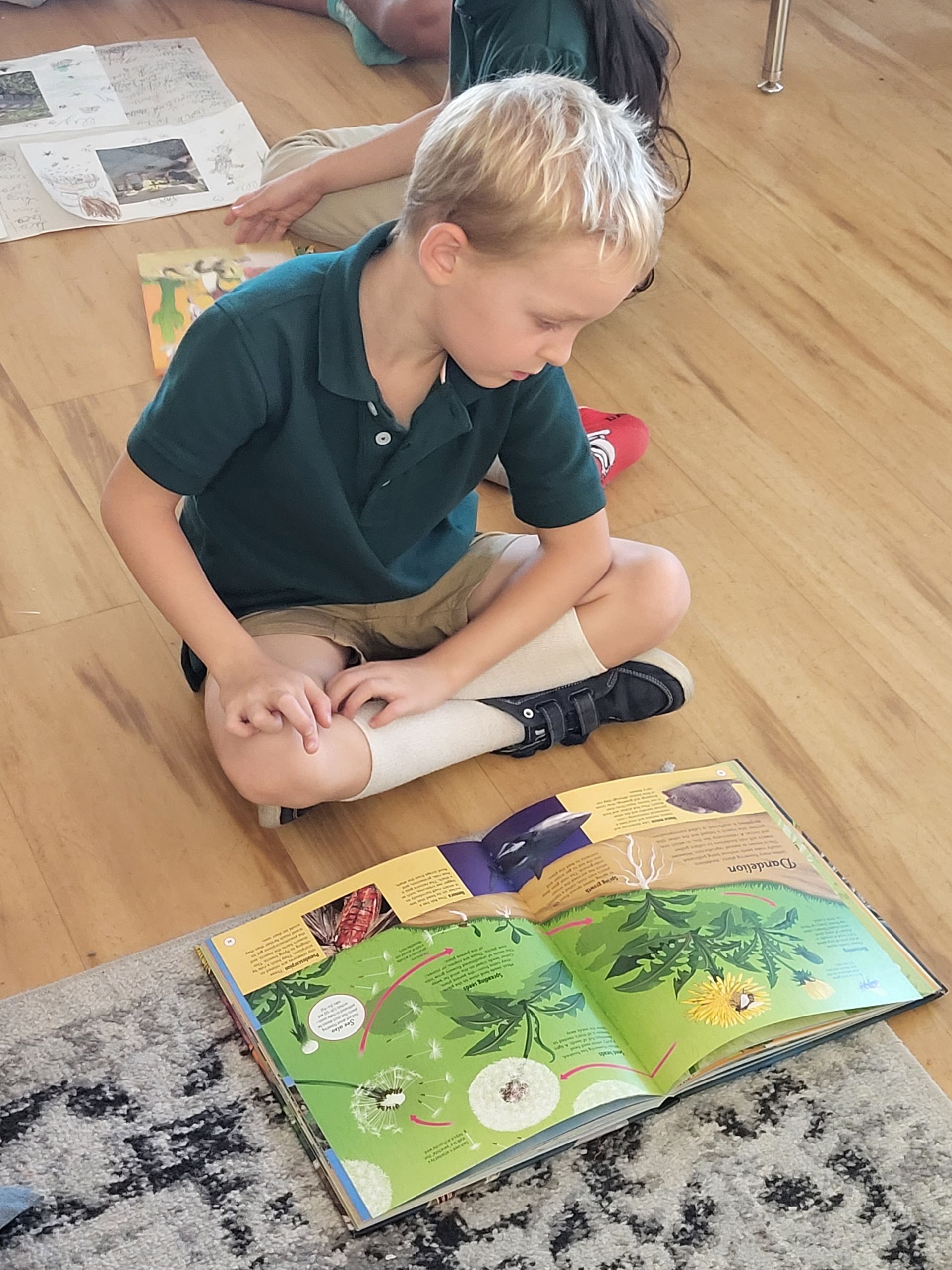

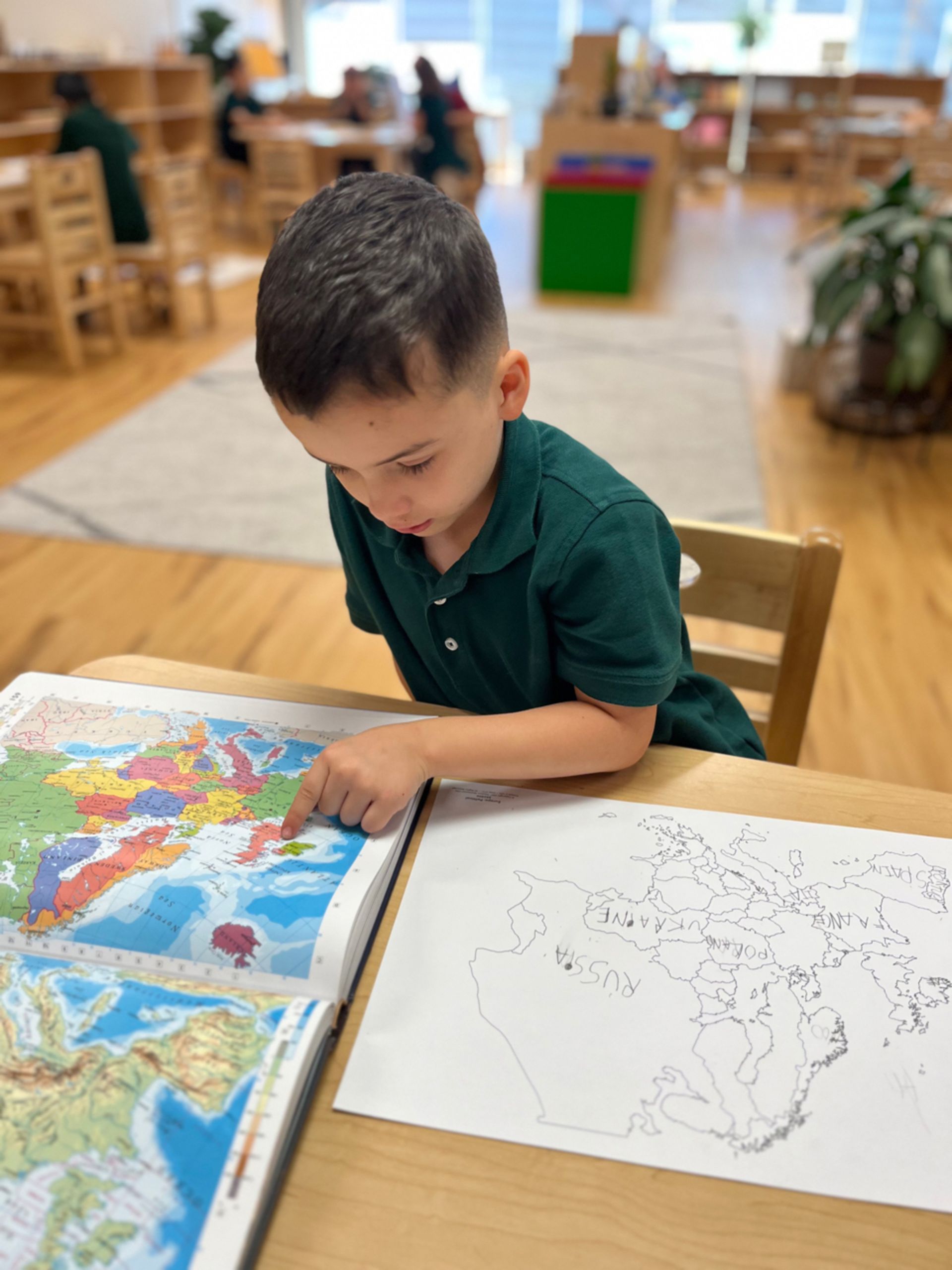

In Elementary, we don’t just invite children to receive lessons with new materials; we invite them to pursue their own interests after we present the main concept of a topic. Their rational minds crave challenges to continue growing, discovering how the world works. Now that they have the vocabulary to describe their environment, they need to explore beyond the classroom walls.

When a child asks a question, we encourage them to research the answer. We guide them to develop the skills needed to define what they want to know, turning their initial curiosity or doubt into a structured inquiry.

The dictionary definition of research is “to study a subject in detail, especially to uncover new information or reach a deeper understanding”. However, Montessori challenges us to approach research in a unique way. As Lillard explains:

“Montessori children pursue their own projects, just as do researchers in their laboratories. Like university researchers, children choose what they want to learn about, based on what interests them.” (Lillard,Montessori: The science behind the Genius, p.43)

Here are some of the benefits children experience when doing research in an Elementary class:

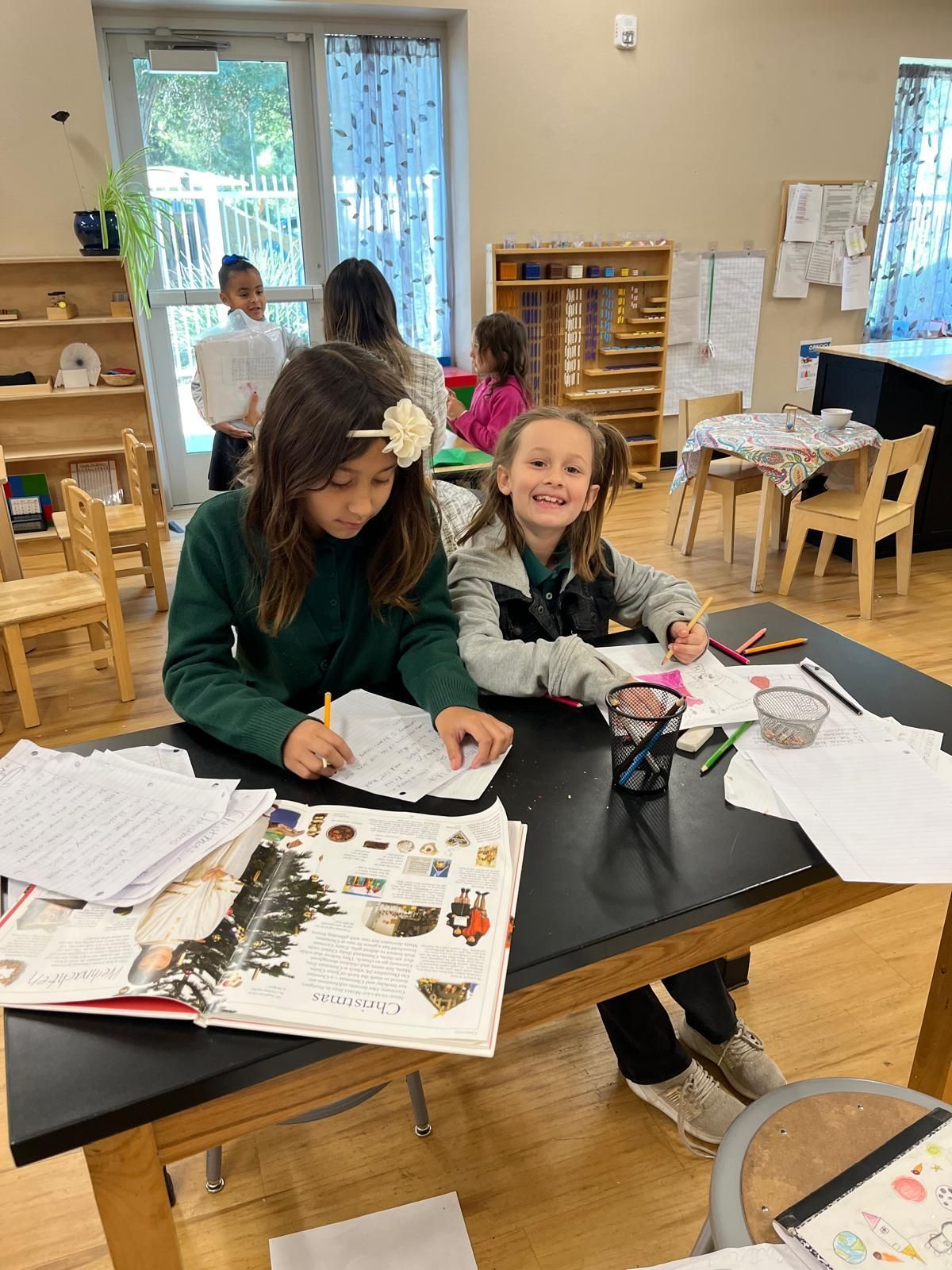

1. Connecting with Their Interests

When a child is intrinsically motivated, their work becomes meaningful. This makes them more focused, and concentration becomes a gateway to developing a love for learning. Research allows them to dive into topics that spark their curiosity, making the learning process feel personal and important.

2. Working in Groups

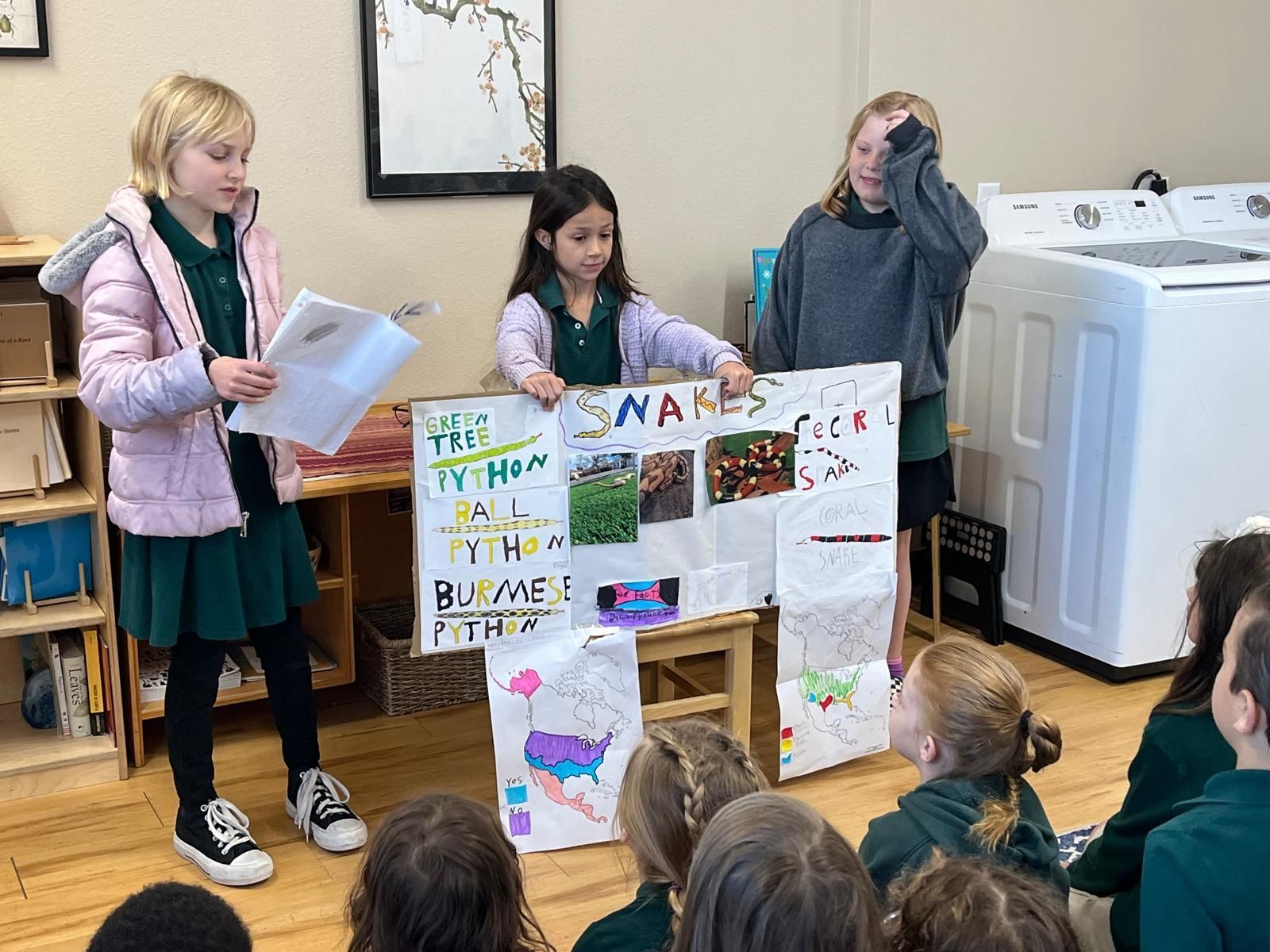

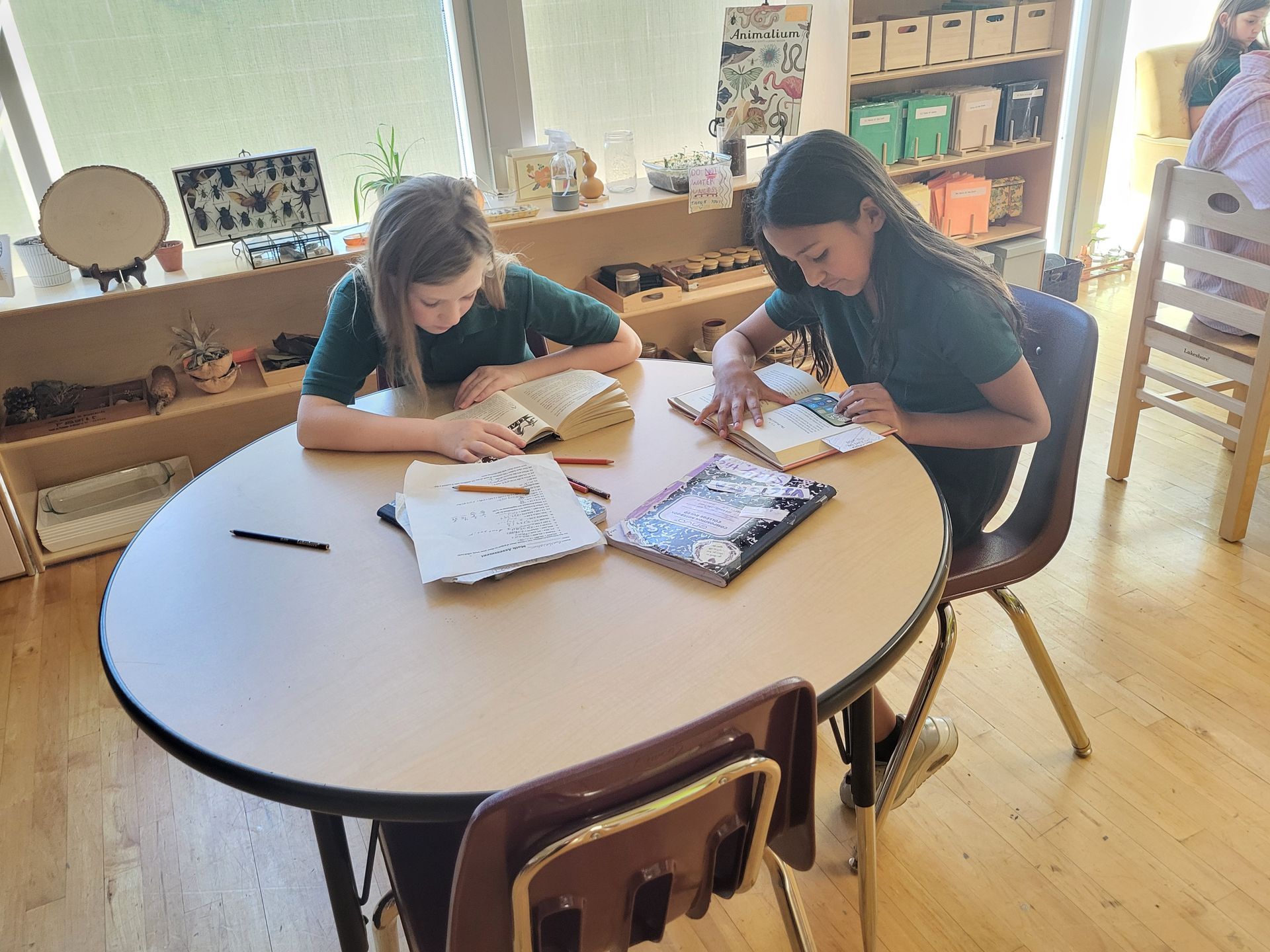

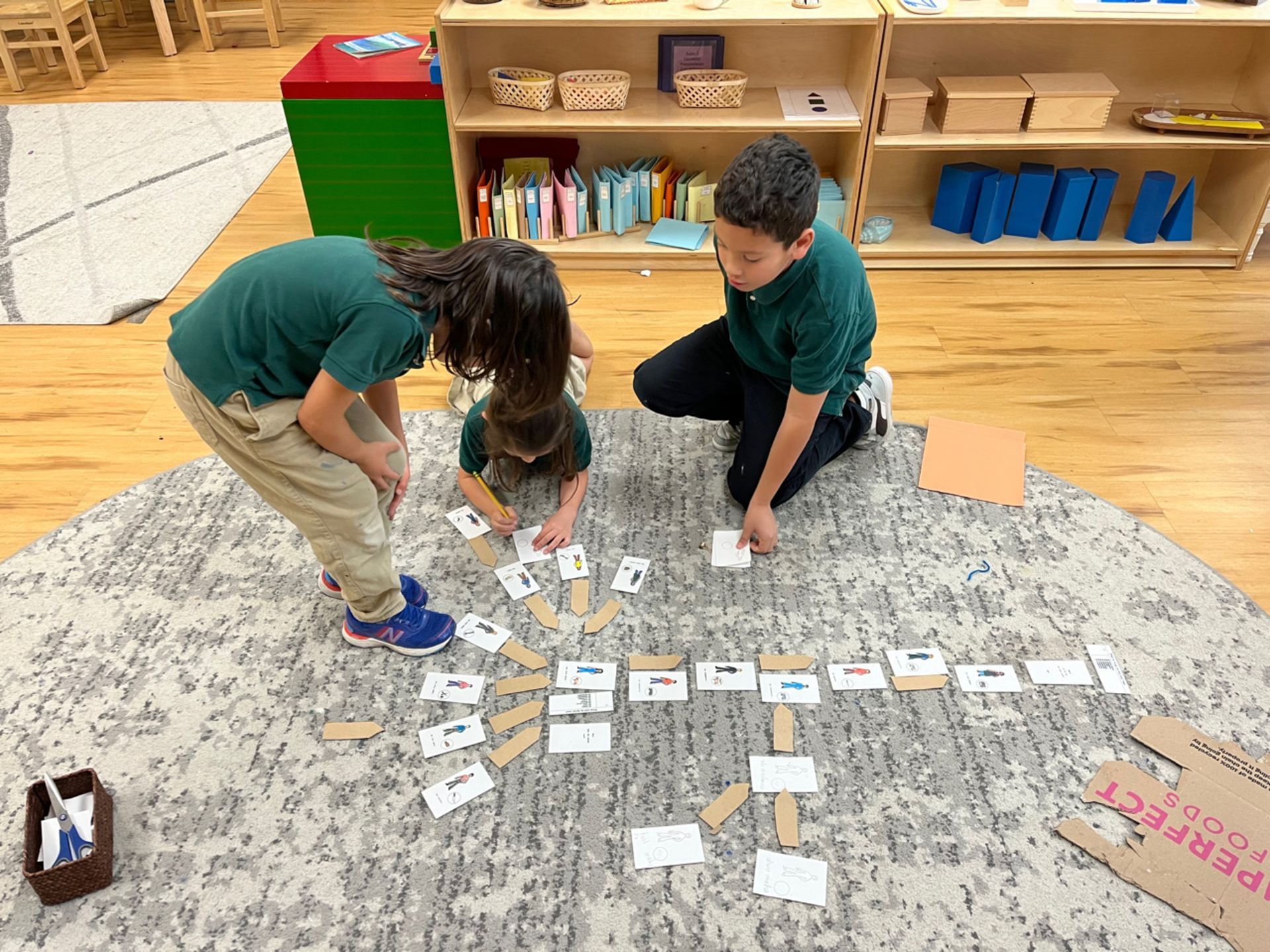

At the Elementary level, children are eager to share their ideas with their peers. Group work challenges them to collaborate and teaches them how to work with others. As guides, we help them divide tasks and organize efforts toward a common goal. They learn to create plans, whether it's deciding when to meet, what resources they need, or simply how to manage conflicts in a group setting.

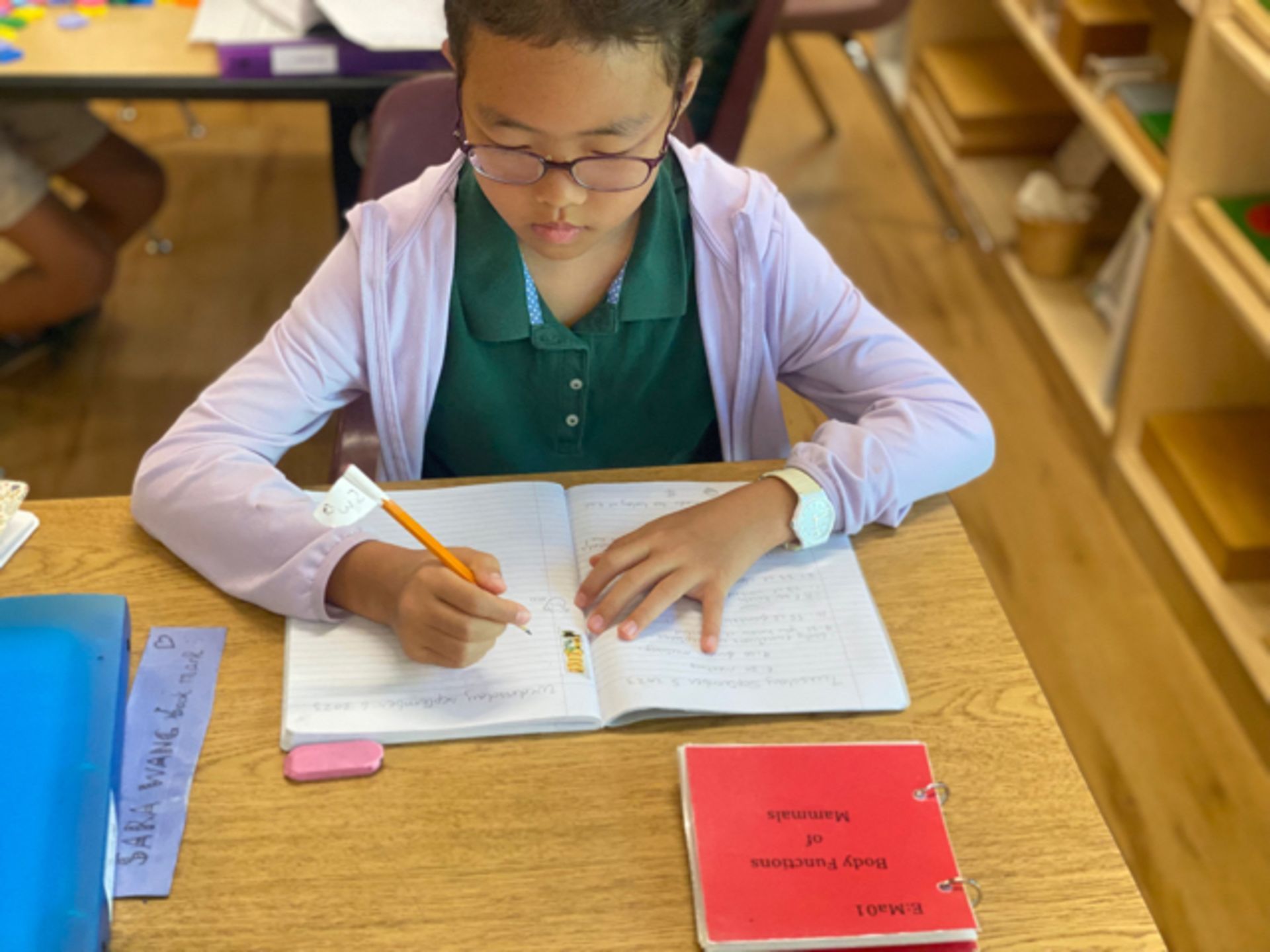

3. Organizing Their Ideas

Research requires children to read, summarize, and organize information, separating what’s relevant from what’s not. This process helps them refine their writing and learn how to express their ideas clearly. For example, writing a letter to request an appointment is different from crafting an instructional text, and both forms help them communicate with purpose.

4. Exploring Different Ways to Express Their Findings

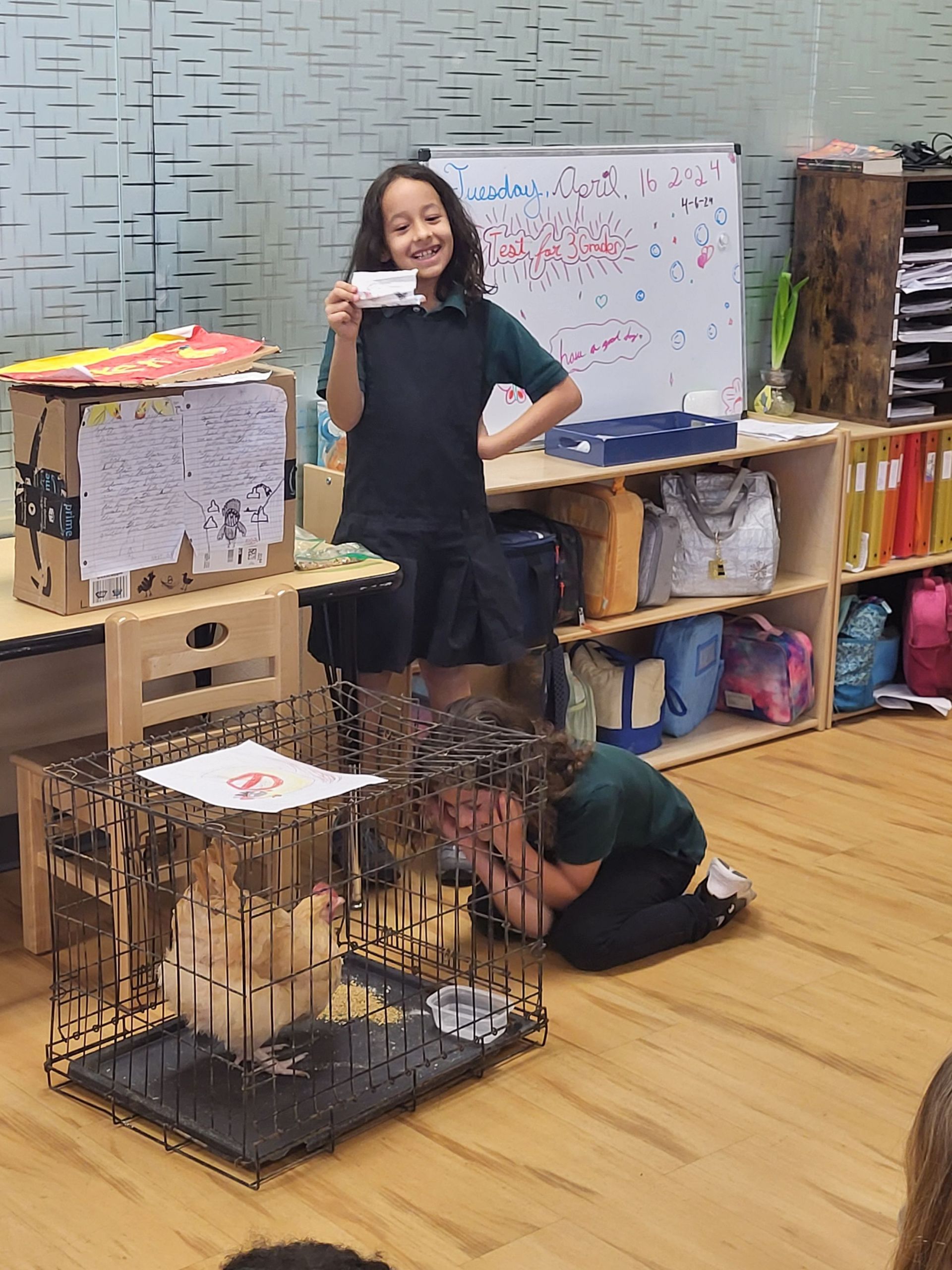

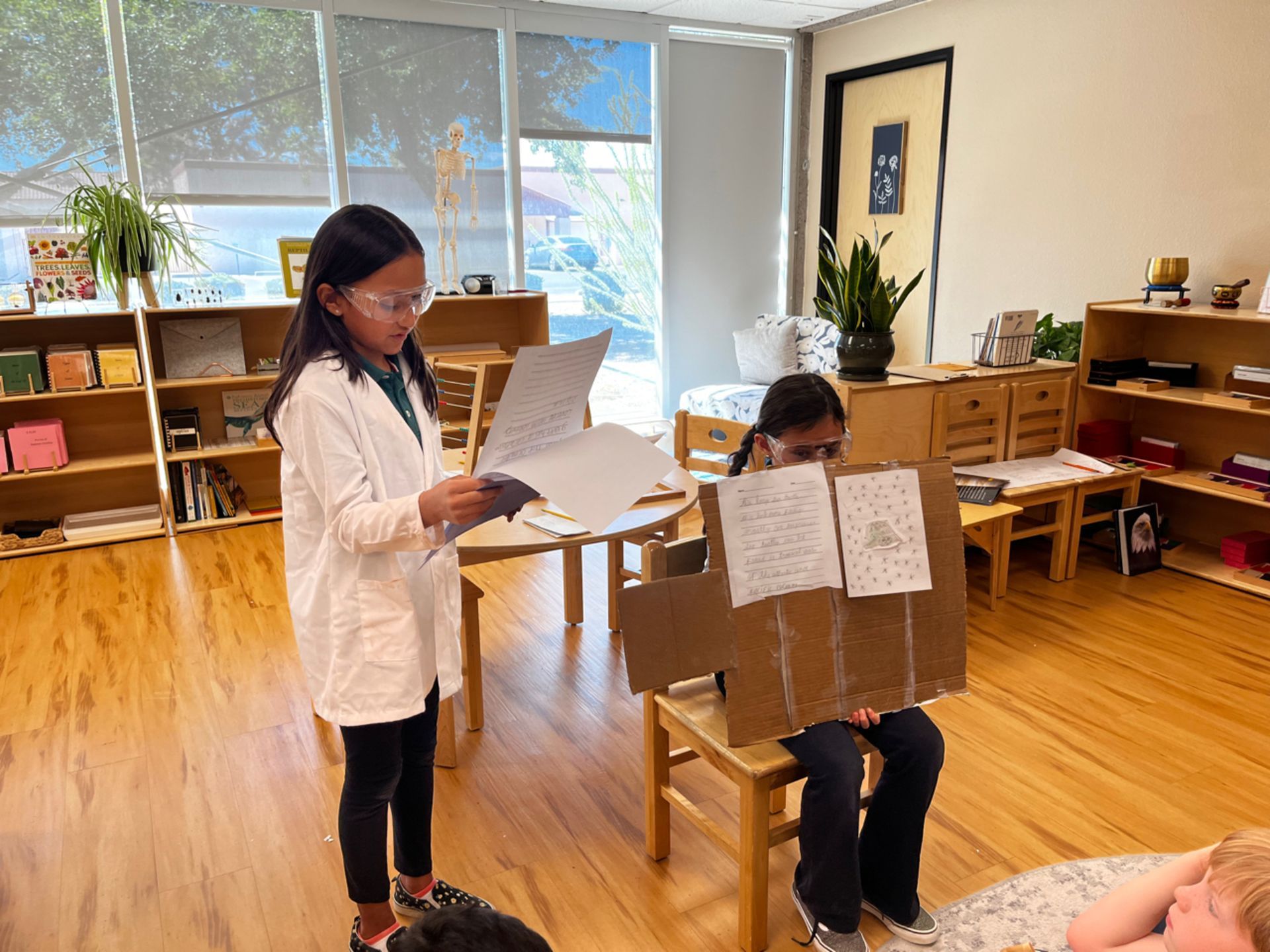

Children have the opportunity to present their research in various creative forms. They can model, paint, write songs, create books, or even act out their findings. This variety allows them to express themselves in ways that make them feel confident and excited.

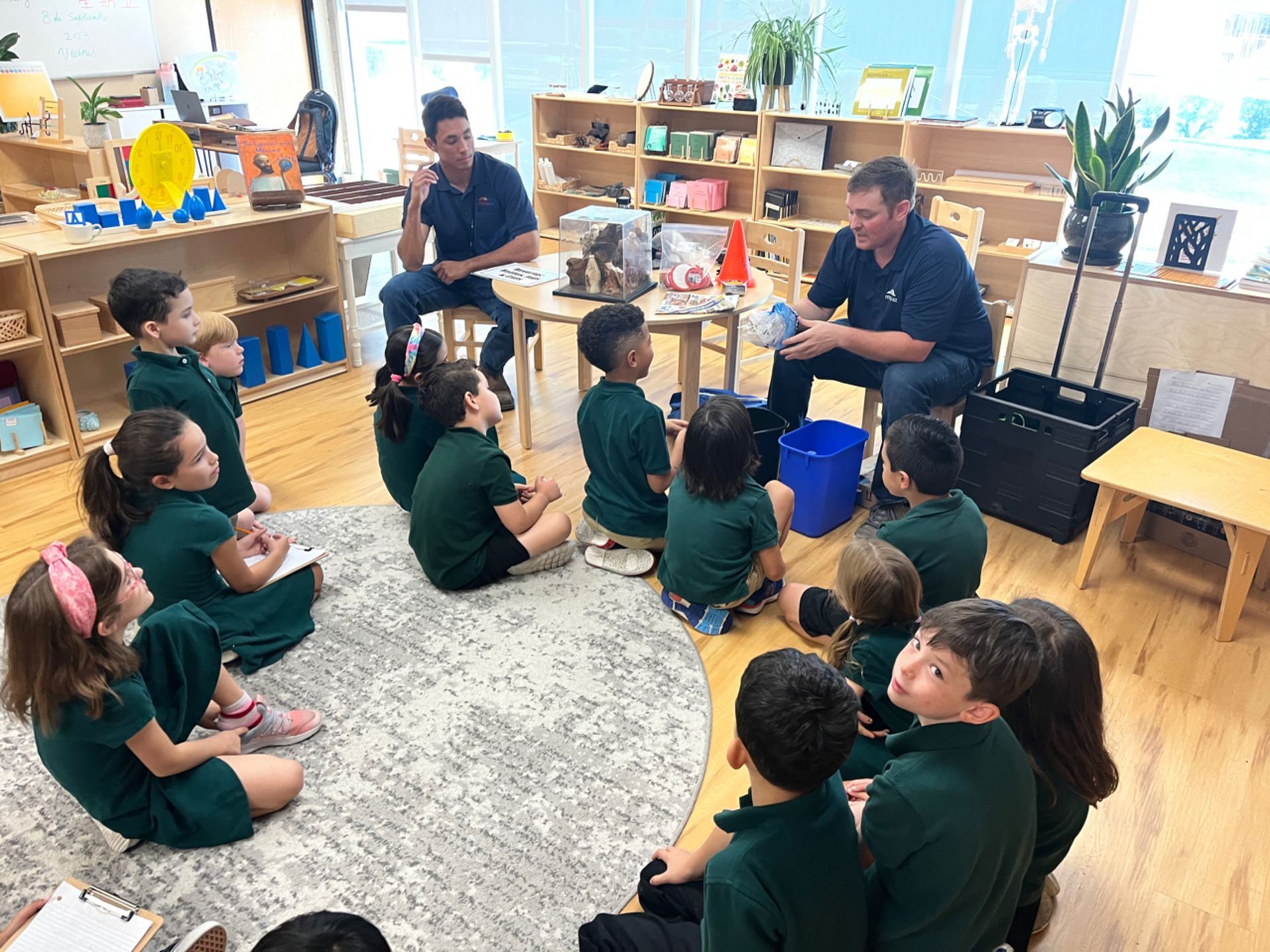

5. Going Beyond the Classroom

In our class, we provide books on a wide range of topics, which often sparks the desire to seek more information outside the classroom. Children may visit the library, contact specialists, go to museums, or explore areas in their community to gather more details. These experiences help them understand that learning extends far beyond the classroom walls.

6. Understanding the Laws of Society

As children venture outside the classroom, they discover that society has its own rules and structures. Crossing a street, taking a bus, visiting a factory, or setting up a meeting challenges them to adapt to new contexts and situations. These experiences teach them important life skills and how to navigate the world around them.

7. Challenging Themselves

Throughout the research process, children face various challenges, and sometimes frustration sets in. Many may feel like quitting, but they are pushed to develop resilience. They learn to listen to others’ opinions, express their own ideas confidently, and collaborate toward a shared goal.

8. Developing Oratory Skills

When they finish their project, children have the opportunity to share their findings with the class. Presenting their research helps them practice speaking skills: becoming fluent, modulating their voice, structuring their thoughts, and using pauses to capture their audience's attention. These skills are not only valuable for the project at hand but will serve them well in any future presentation.

Cosmic Education offers children the opportunity to discover themselves and their place in the world. At the heart of this approach is the power of research — a tool that connects children with their own interests, fueling their curiosity and sense of wonder. Through research, children explore the vastness of knowledge, developing a deeper understanding of themselves and the universe around them.

To end, I’d like to share a powerful quote from Maria Montessori:

“The laws governing the universe can be made interesting and wonderful to the child, more interesting even than things in themselves, and he begins to ask: What am I? What is the task of man in this wonderful universe? Do we merely live here for ourselves, or is there something more for us to do? Why do we struggle and fight? What is good and evil? Where will it all end?”

(Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential, p.6)

Romina Acuña

Lead Lower Elementary Guide

Published: December 2024

Big Work in the Elementary Classroom

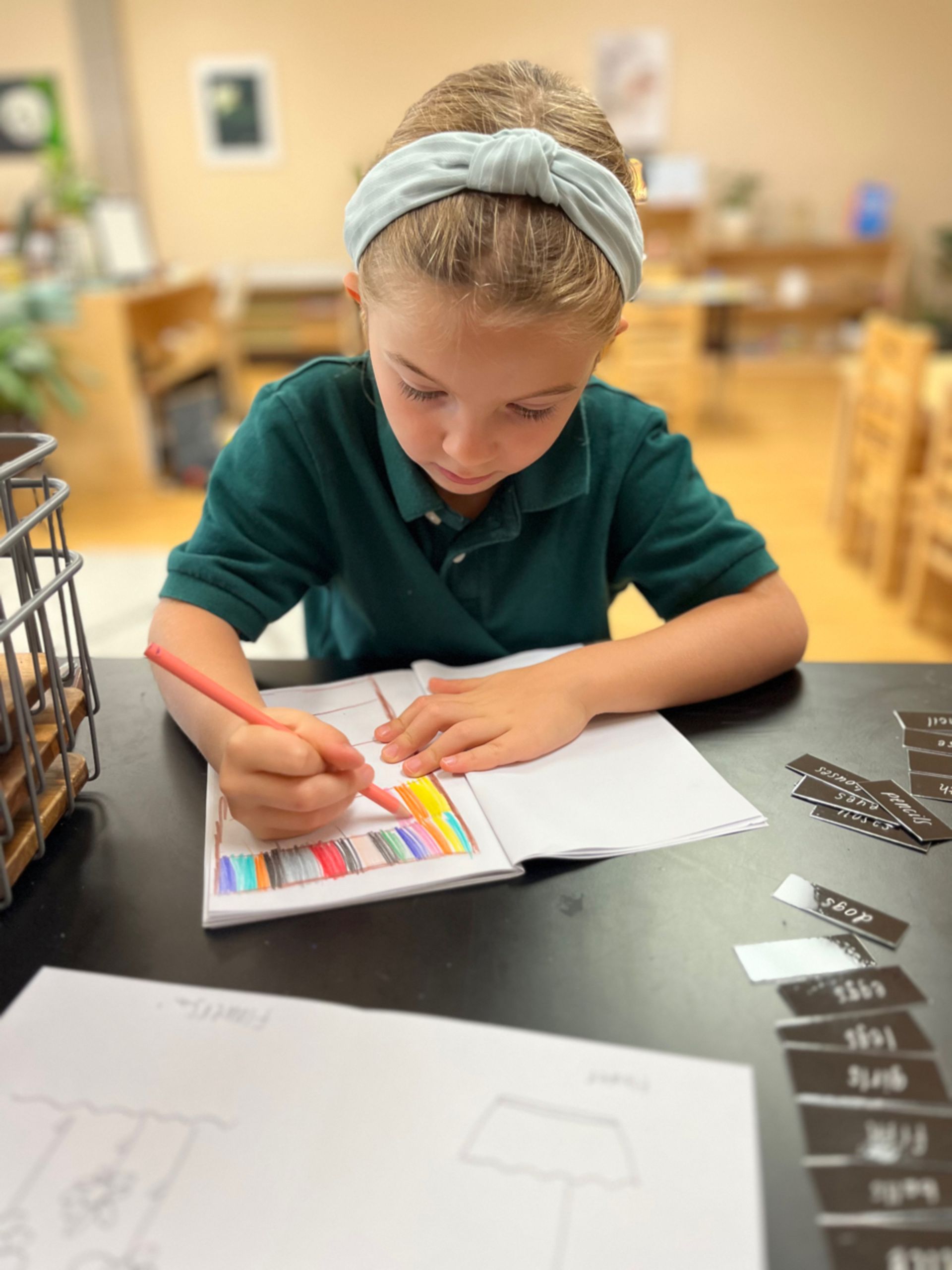

Elementary classrooms are dynamic environments in which there is a great variety of work going on. Children are creating, researching, building, collaborating, thinking, learning, questioning, imagining, and following their passions. The Elementary classroom is an environment where students are excited to learn and grow.

Elementary guides create a culture of work in their environments. In some environments, the students refer to it as “a beautiful work classroom”. Beautiful work does not mean work that meets some artistic standard, rather it is big work decided upon by the students and pursued with thought, care, deliberation, and an investment of time.

How do Elementary guides make this happen? This is where the artistry of teaching in the Montessori Method comes in!

1. They give exciting lessons. Without the beautiful lessons, there will be no beautiful work. The psychological characteristics of the second plane child include “Imagination”. Guides use this characteristic and give inspiring lessons, tell exciting stories, spark the children’s interest, ask thoughtful questions, and then they give the children the freedom to work.

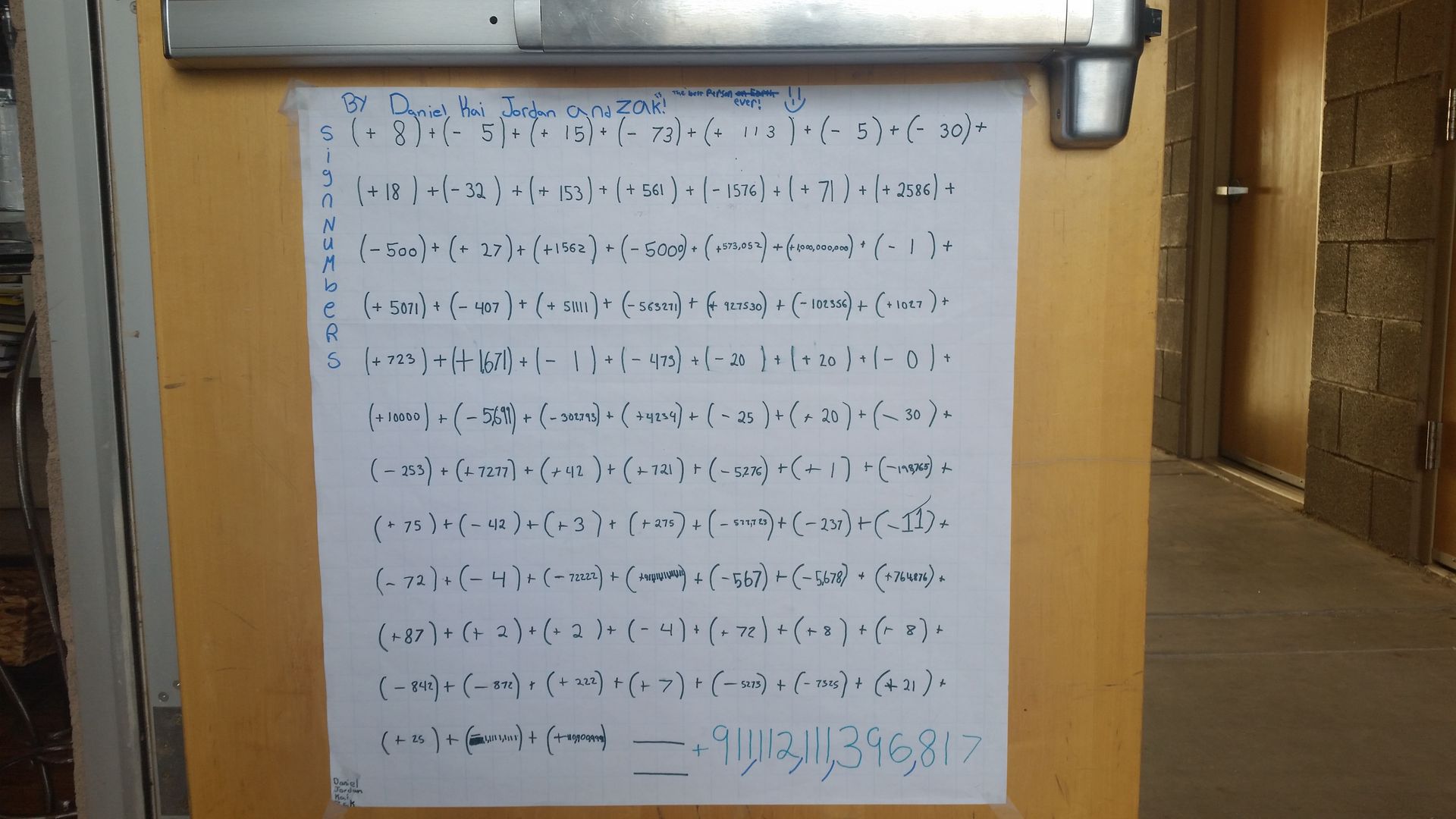

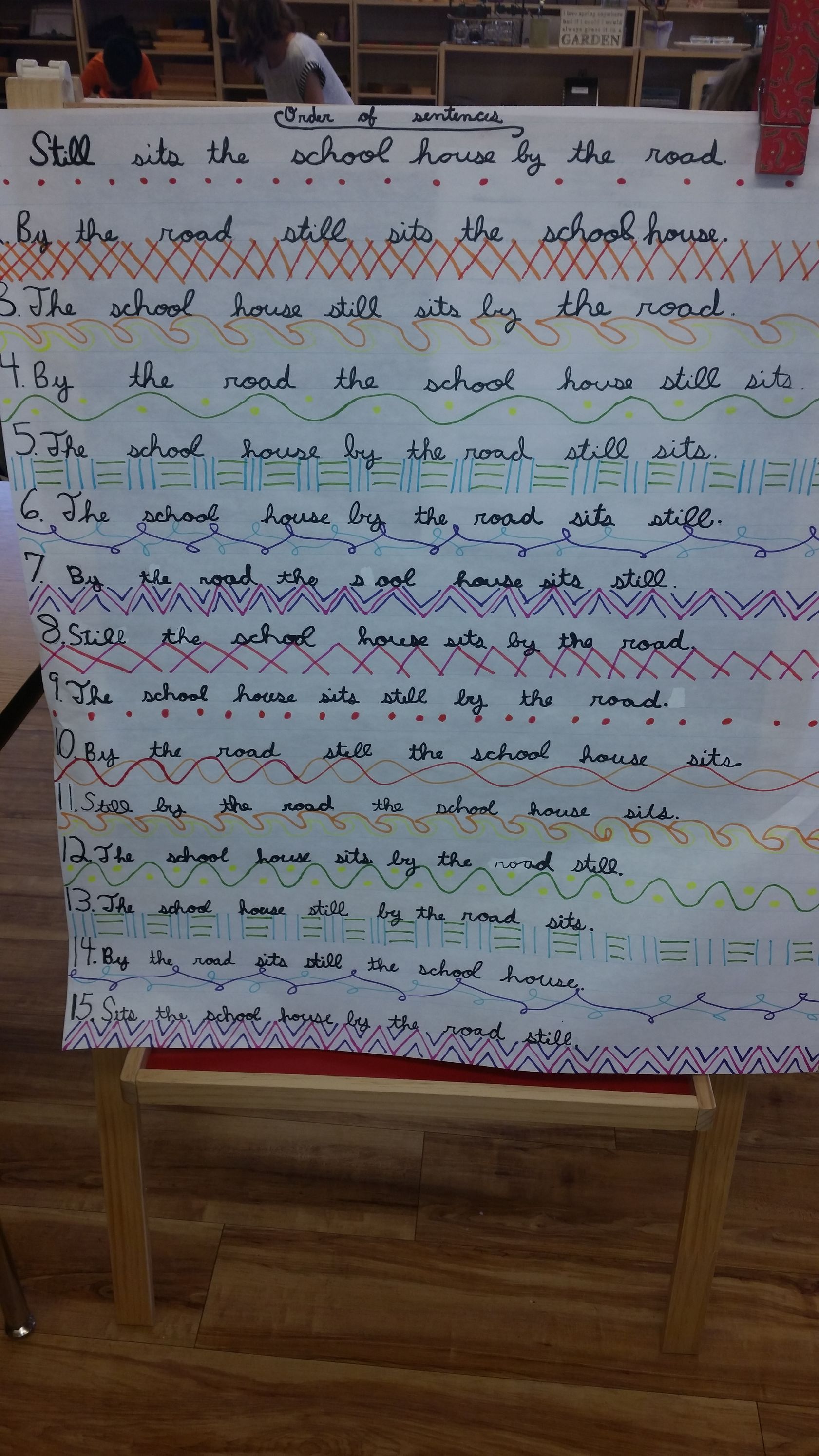

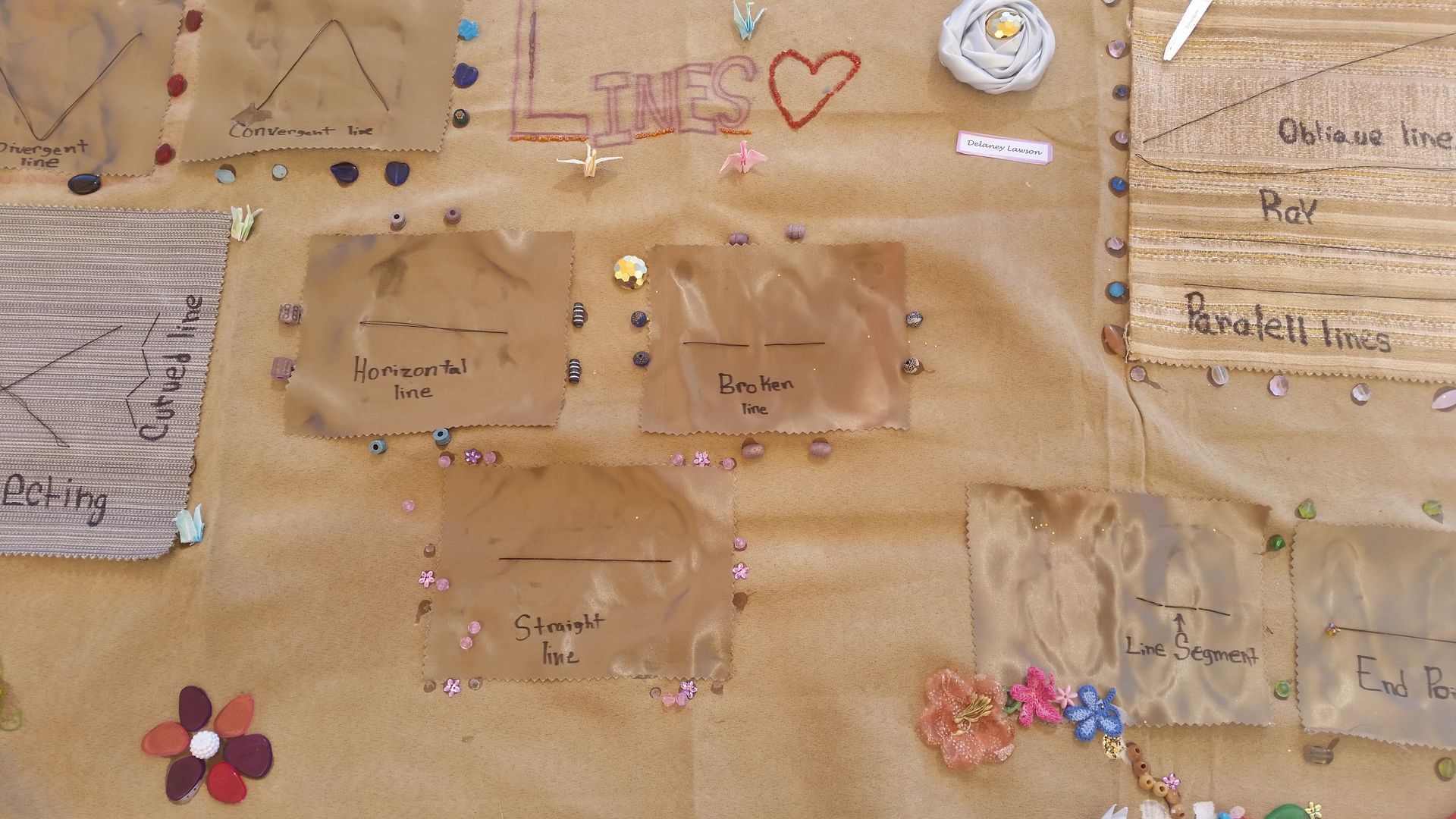

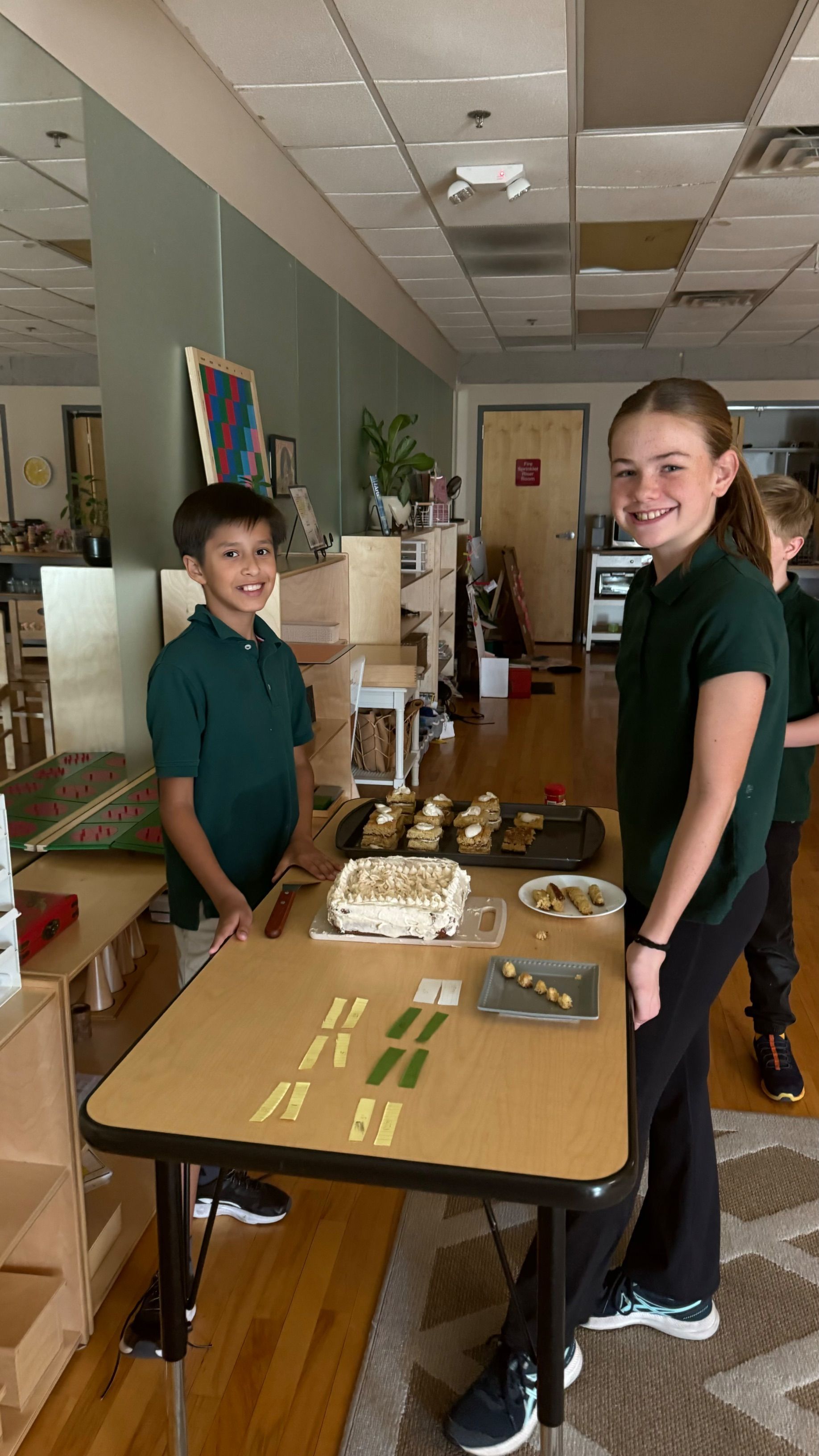

2. They set an expectation for work. Freedom in the classroom environment means freedom to WORK. Not working is not an option. How they work, where they work, with whom they work, and what they work on are the freedoms we offer in an Elementary classroom. In a very young classroom, we may have to give examples of what follow up work to a lesson could be, but we are careful to not impose our ideas upon a child. We know the children’s ideas are far superior to anything we could come up with! After a lesson on Types of Lines, for example, the guide would say, “I wonder how you could practice this lesson? Perhaps you could make a book? A scroll? A Poster? You could sew the lines and make a pillow! How about using toothpicks? Q-tips? Yarn? Popsicle sticks? Or you could bake pretzels and position them as lines!!” These are all examples of big work!

3. They provide the materials for big work. In the elementary classroom, we provide materials for the children to work. We have large rolls of plain paper, huge pieces of graph paper, colored paper, colored pencils, gel pens, markers, paint, cardboard, glue, sequins, yarn, tape, book binding materials, popsicle sticks, canvases, glitter, “special” and beautiful paper…all of these are available to the students at all times (not just for art lessons) so they can think, create, and work outside the “pencil-paper” box.

4. They provide uninterrupted time for big work. After guides have given the lessons, set expectations for work, and provided the materials for work, the students will be working! It is at that time that guides need to step back, let them work, and protect that work time. If they are engaged in constructive and productive work, we let them do it, no matter how long it takes. The uninterrupted work cycle is specifically designed for this, to let the students do their work without interference. The things they learn from working on their own are invaluable and cannot be taught: independence, responsibility, collaboration, compromise, precision, revision, perseverance, dedication, and satisfaction of work done independently. The beautiful work that come from this time is a bonus!

Nothing brings us greater joy than those moments when there is no one to give a lesson to as everyone is engaged in productive work! You can observe that amazing hum of happy working students and will see groups of children working together on creative and inventive projects that display their understanding of concepts learned in a way that writing them down with paper and pencil never could. That is what we strive for…environments that are the opposite of “paper & pencil” classrooms.

Shahnaz Currim

Elementary Program Director

Published : November 2024

Freedom and Responsibility

Dr. Maria Montessori discovered through her observations of children that freedom is essential for the child’s individual construction. What we must think of is how this is implemented and balanced within the classroom. Freedom does not mean that the child is free to do whatever they want within the classroom and even in the home environment as this would result in chaos. Reasonable limits need to be set with these freedoms. The abilities of each individual child will show how much freedom is suitable for them. This means some children can handle having more freedom than others. The guide’s careful observation of each child helps them to know what the needs of the children are.

When giving the children freedoms within the classroom and home environment we need to make sure the children understand the corresponding responsibilities that go along with their freedoms. These freedoms are not given all at once. Again, it depends on the child and what their choices and actions show they are ready for.

In the prepared environment, we gather the children together at the beginning of the school year to discuss Freedoms and Responsibilities as they pertain to ourselves and the community. The children decide what the freedoms and responsibilities will be, with guidance from the teacher. With this help, the child recognizes the reality of the freedom that they have been given through modeling by others and within themselves. The child comes to these realizations because of their reasoning mind, a characteristic of children in the second plane of development.

Children are given the freedom of choice within the prepared environment. Allowing them to make good choices, however knowing that they will make the wrong choices occasionally. In this they are learning how to take personal responsibility for their actions and choices and are doing so without the guide helping them out. This is helping the child to understand what their responsibilities are and how they balance with the freedom.

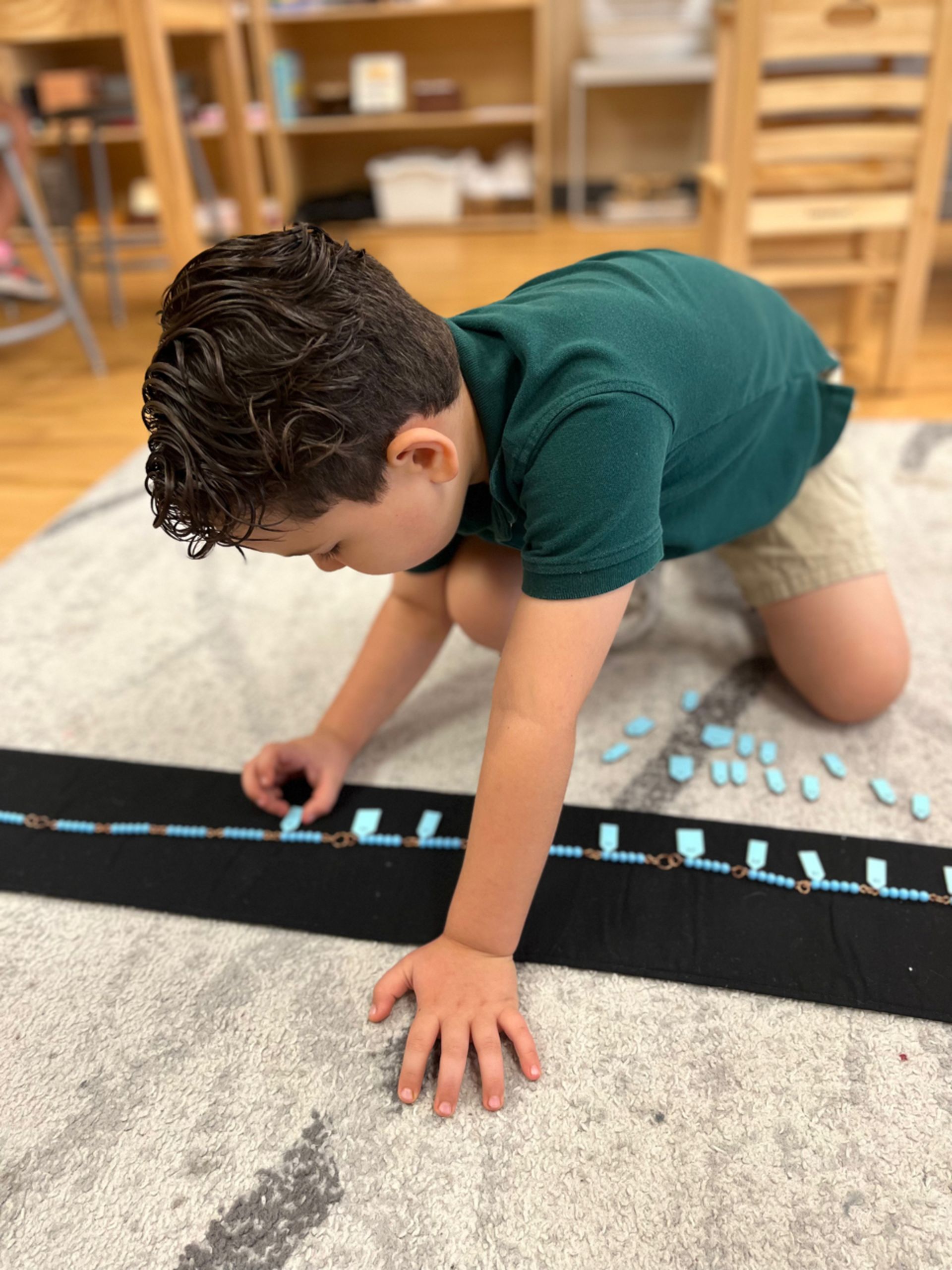

Freedom of Choice allows the child can choose what to work on, who to work with, how long to work for, and where to work in the classroom. The work the child does in the classroom is their choice once lessons have been given. The child can then choose how to continue following up in that area of interest. The freedom to choose their work also comes with responsibility toward that work. The children are required to keep track of the work they have done in a record book, where they write the date along with the time and the work they do throughout the day. The record book is also helpful to children who may be having a hard time choosing what to work on as they can refer to it to see what lessons they have had. The record book also holds them accountable for their work and the time spent on it.

Freedom to Move is another freedom given to children in a Montessori classroom. They are able to move about the room throughout the day without assigned seats or a set duration of time put upon them. If they feel the need to go into the outdoor environment to work, this can be an option as well. Within this movement the child has the expectation to have awareness of others working around them, along with walking respectfully throughout the room, and walking around any work rugs on the floor.

In the Second Plane of Development, the years between 6-12, the child is working towards discovering where they fit into society. Having the Freedom to Go Out of the classroom is a great opportunity for the children to work towards their self-construction. The children are in charge of all aspects of planning the Going Out, including calling to find out needed information, coordinating transportation, and talking with others outside of their classroom community. There are always going to be expectations set and responsibilities met before a child is ready for this big work.

All the freedoms the child has in the prepared environment have limits. In the work that the child does, they are expected to record that work along with working constructively. We also are required to fulfill the Arizona State Standards, so this is an opportunity to show the children what is expected of them in society. We also have individual meetings with the children. This is a great way for the child to be accountable for their own productivity and to notice when there are areas that may need more attention.

Another big responsibility is grace and courtesy. As a community we all do our part. The prepared environment belongs to the children, so it is important for them to take care of their space and have pride for the beautiful environment. The children choose contributions within the classroom and complete these tasks for some of time. At home you may call theses contributions “chores”. A child may be taking care of the classroom pet or doing the dishes daily. These contributions change after some time, giving everyone the opportunity to participate in the care of the classroom environment. This work helps develop confidence, responsibility, and community.

Freedoms and responsibilities are the framework of a well-structured environment. Having these expectations in place not only in the classroom, but also at home, help with self-discipline and responsibility and will also help the child to be more independent. As the children are constructing themselves in this stage of life, having freedom within limits aids the child’s development.

April Knight

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: October 2024

Imagination and the Reasoning Mind

In Montessori philosophy, children in the second plane of development ( the ages of 6 and 12) have a reasoning mind. During this second plane of development, children can use their imagination and reasoning to develop more advanced learning, including creations, investigations, and calculations. They also begin to develop the ability to distinguish fact from fiction and real life from fantasy.

But, what do we understand about the reasoning mind and what kind of activities do we provide to support this fundamental ability during the second stage?

First of all, this reasoning mind is the one that will lead the child to achieve abstraction, but an abstraction that is not only related to mathematics and numbers.

This abstraction goes hand in hand with imagination. In Montessori, we help the acquisition of abstraction through the five “Great Lessons”. These stories will open the doors to fundamental elements and concepts of history, science, biology, chemistry, language, geography, and math.

Through these stories, some of which are accompanied by experiments, charts or Timelines, children will understand through their reasoning mind and their great imagination, about the creation of the universe and our planet and about how life began to develop billions of years ago. They also learn about the arrival of men and women after an incredible evolutionary process leading to Homo Sapiens and how we continue to develop science, art, and society day by day. Elementary children, thanks to their reasoning mind and great capacity for imagination, can travel millions of years back in time and understand the mysterious creation of our vast universe with its galaxies, stars, planets, and celestial bodies. They also can understand how the natural laws that govern and order the functioning of our planet work. They can imagine life in the Stone Age and how this human being was able to overcome all kinds of obstacles to survive.

These incredible stories are the key to their imagination for later work, through which they will investigate and reflect on understanding this complex scenario more and more.

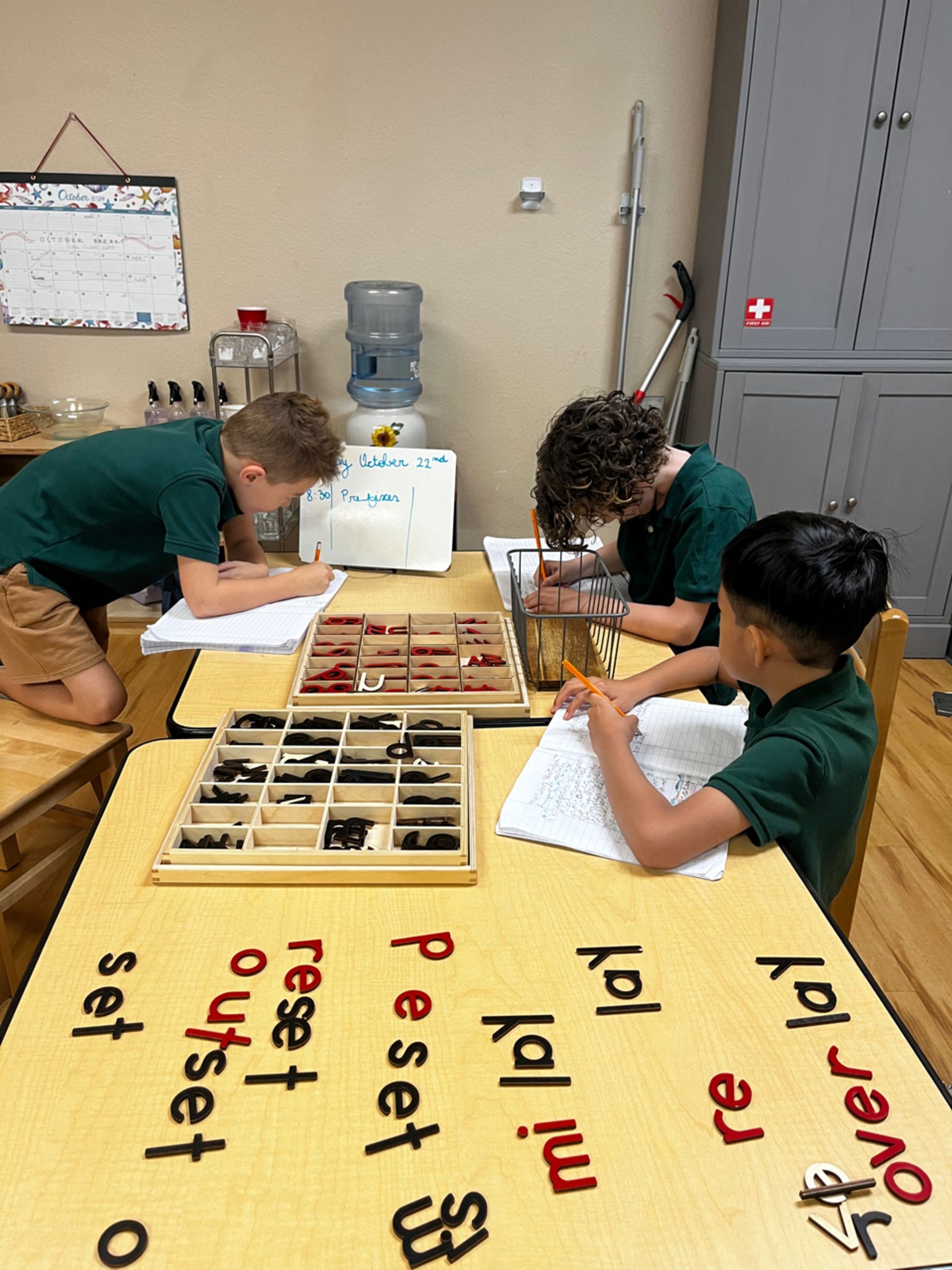

Also, during this second stage of development, the child, using his reasoning mind, imagination, and the use of concrete materials, will be able to acquire abstract concepts such as grammar, which will be included little by little in writing and research. They will discover and understand the formulas behind the binomial and trinomial cubes, and many other abstract concepts.

To support children in this second stage of development, the adults who interact with them have a valuable mission, which is to give them the greatest number of real experiences that connect them with the functioning of life. If they can see a snake or a volcano, they will be able to imagine any type of snake or the different types of volcanoes. Each real experience will be an indelible mark in the minds and imaginations of our children. A walk up a hill, a trip to the park, or a visit to the museum will be the best and most precious gifts that we can give to our children and students. For this reason, we should try to go out with them whenever possible and invite them to observe and wonder about everything around us.

Paola Bianchi K.

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: September 2024

The Power of Reading

Reading is not only a process of decoding words but also it is a way to access knowledge and imagination. In our classrooms, it plays a really important role in the development of the child. Children in Elementary are in what Maria Montessori called the second plane of development. This plane is marked by a growing curiosity about the world and the ability to think abstractly. Reading becomes crucial at this time, it can help children figure out how the world works, expand their imagination, and develop empathy.

Reading in Elementary

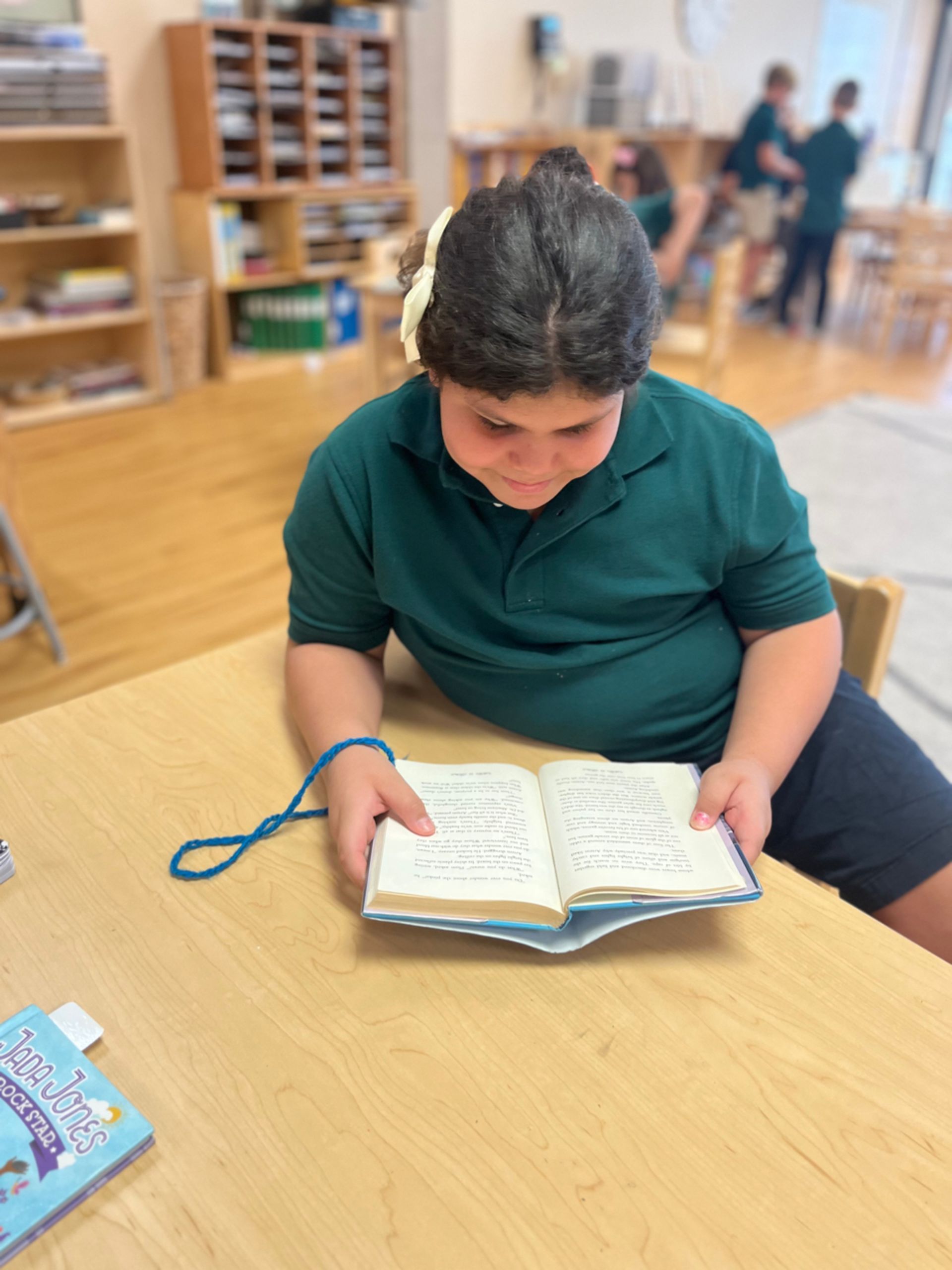

Reading is part of our daily routine. We spend 15 minutes doing silent reading and 15 doing reading aloud. During reading aloud, the guide or the assistant will pick a book and read it to the class. While reading aloud, children can also practice handwork, like knitting, crocheting or decorating their journal.

Why reading aloud? When we read aloud, children are focused on the story, they listen carefully and exercise their imagination. Different books open different doors for discussions. In our class, we just finished reading “Island of the Blue Dolphins”. Children enjoyed the story and we discussed the hard situations faced by the main character. We talked about the value of friendship, resilience and the importance of perseverance while encountering great difficulties.

When we pick a book for reading aloud, we can choose a book that goes beyond everyday language, that exposes children to richer vocabulary, complex sentence structures, and also, explores new ideas. I remember having beautiful conversations about peace, hope, and perseverance after reading “Sadako and The Thousand Paper Cranes” by Eleneor Coerr with the class last year. This helps them to develop empathy and a deeper understanding of right and wrong, contributing to their moral development. Dr. Montessori emphasized the importance of exposing children to high-quality literature: “By listening to a well-told classic, they do not just hear words, they experience the composition.”

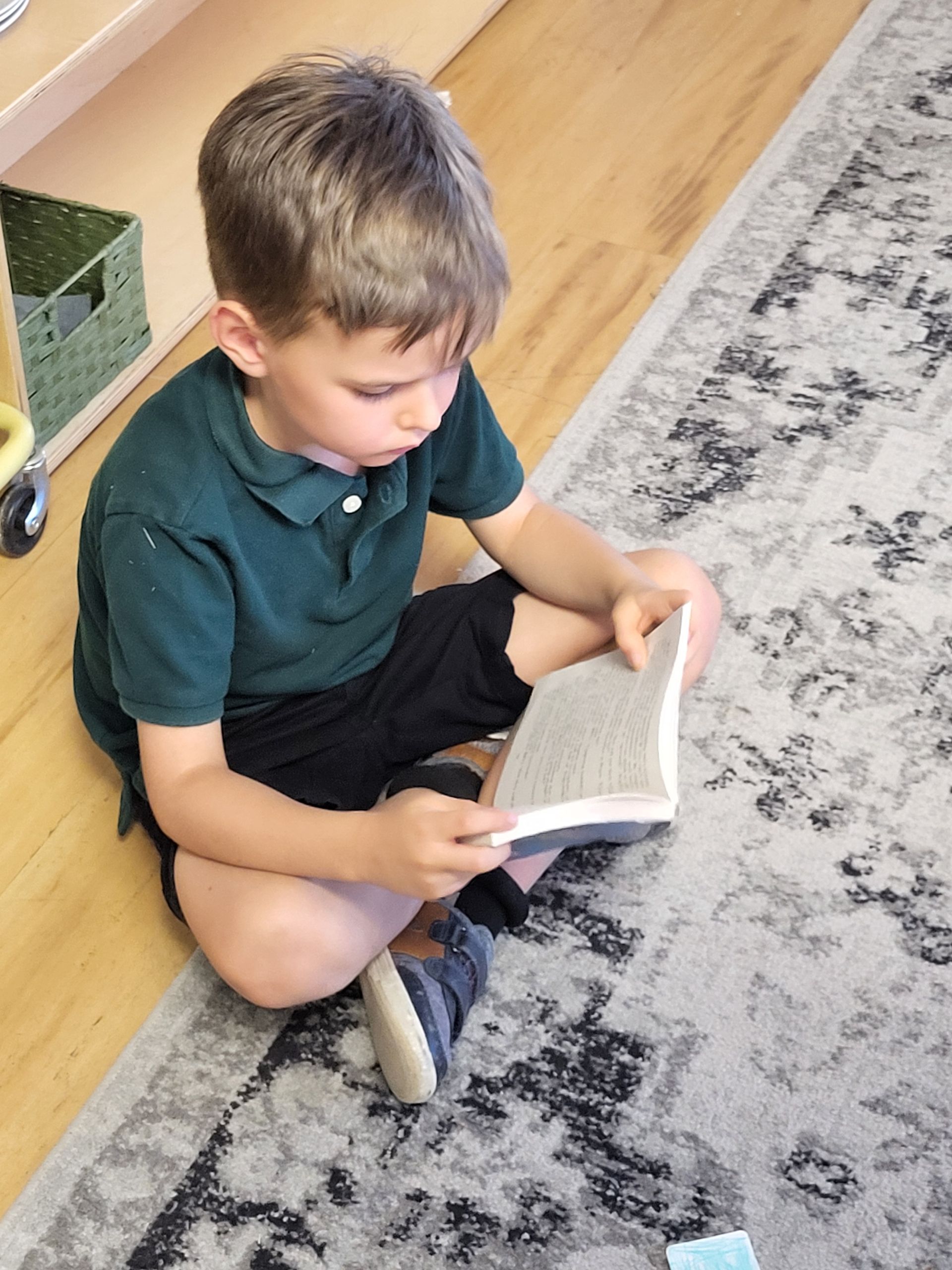

Silent reading also offers children the opportunity to exercise their reasoning mind. As they read independently, they can make connections between the text and their own experiences. In different books, children are going to be exposed to different topics, tricky situations, or explore different times in history and emotions that do not always have an easy answer.

Reading is also fundamental for Cosmic Education. Cosmic Education is a Montessori concept that seeks to provide children with a whole view of the universe and then, their place within it. Children are introduced to different subjects that they explore through reading, from biology to history, geography, and art. These subjects don’t go in isolation; they all come together to paint a bigger picture of the universe.

In Cosmic Education, reading helps explore big questions about the world, children develop a sense of wonder and responsibility for the environment and society. Whether they are reading about the formation of the Earth, early human beings, or wherever their research might take them, each subject is part of a larger narrative that supports their understanding of the world and their role in it.

The Power of Reading

Many researches show that reading has positive impacts on children’s development. It helps them to be more empathetic. It contributes to their intellectual development, as well as their social development. We live in a fast-paced world, children are used to instant notifications and answers, immediate access to videos, and games. Reading can be a much better alternative, it requires sustained focus and invites children to slow down.

Building a community of readers is an important goal in our class. We encourage and model conversations about books, fostering an environment where children feel excited to share about their favorite book, where they recommend books to each other. In “The Book Whisperer”, Donalyn Miller emphasizes the importance of talking about books as a way to establish connection between children. These conversations contribute to their critical thinking because they need to listen to others’ ideas, they can put themselves in other people’s shoes. Sharing their ideas and understanding about a book helps to see themselves as readers and also see reading as a social activity.

In our class, we want to create a space where conversations about books are a regular thing, that way, we will be fostering lifelong readers who see books as a way to connect with others. Parents also play an important role. Children’s love for reading can go beyond our classroom. It is important to establish reading habits at home. You can set some family reading time or reading aloud right before bed or during breakfast. It can create moments of connection within your family, bringing different conversations about values, emotions or just enjoy funny stories together. If you share your enthusiasm for reading with your children that can be very contagious!

In conclusion, reading is a powerful tool that supports the whole development of the child. Whether it's a journey to Narnia, a space battle with Ender, or an exploration of the natural world, reading can help children shape their understanding of themselves and the world.

Laura Ferrando

Upper Elementary Guide

Published: July 2024

101 Things Parents Can Do to Help Children

1. Read about Montessori education and philosophy and how it applies to your child.

2. Subscribe to The Michael Olaf Catalog. This wonderful publication is a clear introduction to Montessori for parents as well as a source book of ideal toys, materials, books, etc. for the home.

(Order form available in the school office.)

Michael Olaf Products Birth to 12+ www.michaelolaf.com

Montessori Philosophy and Practice (E-books) www.michaelolaf.net

3. Take the time to stand back and observe your child carefully and note the characteristics he/she is displaying.

4. Analyze your child's wardrobe and build a wardrobe aimed at freedom of movement, independence, and freedom from distraction.

5. Make sure your child gets sufficient sleep.

6. Make both going to bed and getting up a calm and pleasant ritual.

7. Teach grace and courtesy in the home. Model it. Use courtesy with your child and help your child to demonstrate it.

8. Refrain from physical punishment and learn ways of positive discipline.

9. Have a special shelf where your child's books are kept and replaced after careful use.

10. Make regular trips to the public library, and become familiar with the librarians and how the library works and enjoy books together. Borrow books and help your child learn the responsibility for caring for them and returning them.

11. Read together daily. With younger children stick to books with realistic themes.

12. See that your child gets to school on time -- that is by 8:30.

13. Allow sufficient time for your child to dress himself/herself.

14. Allow your child to collaborate with food preparation and encourage your Extended Day child to take at least some responsibility for preparing his or her own lunch.

15. If possible allow your child a plot of land or at least a flower pot in which to experience growing things.

16. Take walks together at the child's pace, pausing to notice things and talk about them.

17. Help your child be in a calm and prepared mood to begin school rather than overstimulated and carrying toys or food.

18. Eliminate or strictly limit TV watching and replace with activity oriented things which involve the child rather than his/her being a passive observer. When the child does watch TV, watch it with him/her and discuss what is being seen.

19. From the earliest age give your child the responsibility to pick up after himself/herself, i.e., return toys to place, put dirty clothes in laundry basket, clear dishes to appropriate place, clean off sink after use, etc. This necessitates preparing the environment so children know where things go.

20. Hug regularly but don't impose affection. Recognize the difference.

21. Assign regular household tasks that need to be done to maintain the household to your child as age appropriate. (Perhaps setting silverware and napkins on the table, sorting, recycling. dusting, watering plants, etc.)

22. Attend school parent education functions.

23. Arrange time for both parents to attend parent-teacher conferences. Speak together in preparation for the conference and write down questions to ask.

24. Talk to your child clearly without talking down. Communicate with respect and give the child the gift of language, new words and expressions.

25. When talking to your child, physically get on his/her level, be still, and make eye contact.

26. Sing! Voice quality does not matter. Sing together regularly. Build a repertoire of family favorites.

27. Refrain from over-structuring your child's time with formal classes and activities. Leave time to "just be," to play, explore, create.

28. Teach your child safety precautions. (Deal with matches, plugs, chemicals, stairs, the street, how to dial 911, etc.)

29. Teach your child his/her address, phone number, and parents' names.

30. Count! Utilize natural opportunities that arise.

31. Tell and re-tell family based stories. For example, "On the day you were born..."

32. Look at family pictures together. Help your child be aware of his/her extended family, names, and relationships.

33. Construct your child's biography, the story of his/her life. A notebook is ideal so that it can be added to each year. Sharing one's story can become a much loved ritual. It can be shared with the child's class at birthday time.

34. Assist your child to be aware of his/her feelings, to have vocabulary for emotions and be able to express them.

35. Play games together. Through much repetition children learn to take turns, to win and lose.

36. Together, do things to help others. For example, take food to an invalid neighbor, contribute blankets to a homeless shelter, give toys to those who have none, etc.

37. Speak the language of the virtues. Talk about patience, cooperativeness, courage, ingenuity, cheerfulness, helpfulness, kindness, etc. and point out those virtues when you see them demonstrated. (Virtues Project resource information available in the school office.)

38. Refrain from giving your child too much "stuff." If there is already too much, give some away or store and rotate.

39. Memorize poetry and teach it to your child and recite it together.

40. Put up a bird feeder. Let your child have responsibility for filling it. Together learn to be good watchers and learn about the birds you see.

41. Whenever you go somewhere with your child, prepare him/her for what is going to happen and what will be expected of him/her at the store, restaurant, doctor's office, etc.

42. Express appreciation to your child and others and help your child to do the same. Send thank you notes for gifts. Young children can dictate or send a picture. Older children can write their own. What is key is learning the importance of expressing appreciation.

43. Help your child to learn to like healthful foods. Never force a child to eat something he/she does not like, but also don't offer unlimited alternatives! Make trying new things fun. Talk about foods and how they look or describe the taste. Introduce the word "savor" and teach how to do it. Engage children in food preparation.

44. When food shopping, talk to your child about what you see -- from kumquats to lobsters. Talk about where food items come from. Talk about the people who help us by growing, picking, transporting, and displaying food.

45. Provide your child with appropriate sized furniture: his/her own table and chair to work at; perhaps a rocker in the living room to be with you; a bed that can easily be made by a child; a stool for climbing up to sink or counter.

46. While driving, point things out and discuss -- construction work, interesting buildings, vehicles, bridges, animals.

47. Teach the language of courtesy. Don't let your child interrupt. Teach how to wait after saying, "Excuse me, please."

48. Analyze any annoying behavior of your child and teach from the positive. For example: door slamming -- teach how to close a door; running in the house -- teach how to walk; runny nose -- teach how to use a tissue.

49. Spend quality time with people of different ages.

50. Teach your child about your religion and make them feel a part of it.

51. Help your child to have positive connections with people of diverse ethnicities, language, and beliefs.

52. Laugh a lot. Play with words. Tell jokes. Help your child to develop a sense of humor.

53. Share your profession or occupation with your child. Have him/her visit at work and have some appreciation of work done in the world.

54. See that your child learns to swim -- the younger the better.

55. Have a globe or atlas in the house, and whenever names of places come up locate them with the child.

56. Make sure your child has the tools he/she needs -- child size broom, mop, dust pan, whisk broom, duster, etc., to help maintain the cleanliness of the household.

57. Learn to say, "No," without anger, and with firmness and conviction. Not everything children want is appropriate.

58. Arrange environments and options so that you end up saying yes more than no.

59. Refrain from laughing at your child.

60. Alert children to upcoming events so they can mentally prepare, e.g., "In ten minutes, it will be time for bed."

61. Help children to maintain a calendar, becoming familiar with days and months, or counting down to special events. Talk about it regularly.

62. Get a pet and guide your child to take responsibility for its care.

63. Refrain from replacing everything that gets broken. Help children to learn the value of money, and, the consequences of actions.

64. Take a nighttime walk -- listen to sounds, observe the moon, smell the air.

65. Take a rain walk. Wear coats and boots to be protected, but then fully enjoy the rain.

66. Allow your Primary-aged child to use his/her whole body and mind for active doing. Save computers for the Elementary years and later when they become a useful tool of the conscious mind.

67. If you must travel without your child, leave notes behind for him/her to open each day you are gone.

68. Expose your child to all sorts of music.

69. Talk about art, visit statue gardens, and make short visits to museums and look at a couple of pictures. Make it meaningful and enjoyable. Don't overdue.

70. Help them learn to sort: the laundry, silverware, etc.

71. Help them become aware of sounds in words. Play games: what starts with "mmmm?" "What ends with ‘t’?”

72. Organize the child's things in appropriate containers and on low shelves.

73. Aid the child in absorbing a sense of beauty: expose him/her to flowers, woods, and natural materials, and avoid plastic.

74. Help your child start a collection of something interesting.

75. Talk about the colors (don't forget shades), textures, and shapes you see around you.

76. Provide art materials, paper, appropriate aprons, and mats to define the work space. Provide tools for cleaning up.

77. Evaluate each of your child's toys.

Does it help him/her learn something?

Does the child use it?

Does it "work," and are all pieces present?

Is it safe?

78. Refrain from doing for a child what he/she can do for himself/herself.

79. Provide opportunities for physical activity -- running, hopping, skipping, climbing. Teach them how. Go to a playground if necessary.

80. Teach children how to be still and make "silence." Do it together. Children love to be in a meditative space if given the opportunity.

81. Teach your child his/her birthday.

82. Read the notes that are sent home from school.

83. Alert the teacher to anything that may be affecting your child -- lack of sleep, exposure to a fight, moving, relative visiting in home, parent out of town, etc.

84. Provide a place to just dig. Allow your child to get totally dirty sometimes without inhibitions.

85. Refrain from offering material rewards or even excessive praise. Let the experience of accomplishment be its own reward.

86. Don't speak for your child to others. Give the space for the child to speak for himself/herself, and if he/she doesn't it’s okay.

87. Apologize to your child when you've made a mistake.

88. Understand what Montessori meant by sensitive periods. Know when your child is in one and utilize it.

89. Learn to wait. Some things people want to give their children or do with them are more appropriate at a later age. Be patient, the optimal time will come. Stay focused on where they are right now.

90. Play ball together: moms and dads, boys and girls.

91. Tell them what you value in them. Let them hear you express what you value in others.

92. Always tell the truth.

93. Go to the beach and play in the sand.

94. Ride the bus; take a train -- at least once.

95. Watch a sunrise. Watch a sunset.

96. Share appropriate "news" from the newspaper: new dinosaur was discovered; a baby elephant born at the zoo; a child honored for bravery; the weather forecast.

97. Evaluate your child's hairstyle. Is it neat and not a distraction or is it always in the child's eyes, falling out of headbands, etc?

98. Let your child help you wash the car and learn the vocabulary of the parts of the car. With this and other tasks take time to focus on the process for the child more than the end product.

99. Talk about right, left, straight, turn, north, south, east, west, in a natural way so your child develops a sense of direction and the means to talk about it.

100. Place a small pitcher of water or juice on a low refrigerator shelf and a glass in a low place so your child can be independent in getting a drink.

101. If your child is attached to things like pacifiers, start a weaning process.

Enjoy life together!

We are excited to welcome you back for the 2024-2025 school year!!

Shahnaz Currim & the Elementary Team

Elementary Program Director

Published: March 2024

Group Work

Maria Montessori's educational philosophy places a strong emphasis on the significance of group work in elementary classrooms, viewing it as essential for both social and academic development. Montessori observed that even young children demonstrate a natural inclination to engage in structured activities within groups, highlighting humanity's innate tendency towards organization and collaboration. This insight forms the foundation of Montessori education, where group work serves as a cornerstone of learning.

“[An] interesting fact to be observed in the child of six is his need to associate himself with others, not merely for the sake of company, but in some sort of organized activity. He likes to mix with others in a group wherein each has a different status. A leader is chosen, and is obeyed, and a strong group is formed. This is a natural tendency, through which mankind becomes organized. ” Maria Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential, p. 4

Central to Montessori's concept of group work is the recognition of each child's unique role within the collective. In a well-functioning group, individuals assume varying roles, fostering a sense of order and responsibility among participants. Montessori believed that such group experiences not only enhance academic learning but also cultivate essential social skills and emotional intelligence.

Montessori also emphasized the importance of personal discipline within group contexts. Unlike conventional notions of success focused on individual achievement, Montessori asserted that true fulfillment arises from the collective success of the group. By prioritizing the group's well-being over personal accolades, children learn the value of collaboration, empathy, and mutual support, fostering a sense of camaraderie and interconnectedness among peers.

“… the individual thinks more about the success of his group than of his own personal success. ” Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, p. 213.

In the Montessori classroom, group work extends beyond academic collaboration to mirror societal dynamics. Through structured activities and cooperative projects, children learn to navigate interpersonal relationships and contribute meaningfully to their communities. Montessori's holistic approach to education recognizes the interdependence between individual growth and collective well-being, preparing students to become compassionate and socially responsible citizens capable of making meaningful contributions to society.

In conclusion, Maria Montessori's profound insights into group work not only underscore the transformative power of collaboration and communal learning but also evoke a sense of hope and possibility. By embracing the natural inclination of children to engage in organized activities within groups, Montessori education fosters environments where every individual's unique strengths are celebrated and valued. Through group work, children not only develop essential academic skills but also cultivate virtues like empathy, cooperation, and leadership, shaping them into compassionate and socially conscious individuals. As we reflect on Montessori's vision, we are reminded that every child has the potential to contribute meaningfully to their communities and beyond, bringing connection, joy, and positive change to the world.

Hattie Harris

Lower Elementary Guide

Published February 2024

The Reasoning Mind

One of the standout features of children at the elementary age is their developing reasoning mind. Consider the power of imagination as the engine that powers a child’s journey to intellectual independence, and the reasoning mind as the wheels that propel them forward. This developmental stage is all about children beginning to use logical thinking to understand the world around them. Maria Montessori once emphasized the importance of this stage, suggesting that it is about learning to think, not just absorbing facts.

In Montessori classrooms, everything is designed to support this growth. The year starts with the five great stories, which impressionistically unveil the Creation of the Universe, the Coming of the Earth, Humans, Languages, and Numbers. These stories lay the groundwork, sparking curiosity and leading to big questions like, "Why does the Universe exist?" and "How do we stay grounded on Earth?" It's a way to ignite children's imaginations and encourage them to dive deeper. Following these stories, children engage in activities that let them seek answers firsthand, nurturing a love for learning and discovery.

As children grow, their questions evolve. Younger children in primary often ask, "What is this?" while elementary children start pondering the "why" and "how" of things. In a Montessori space, children are guided to find answers through exploration and discovery. For instance, when curious about how many days there are until Christmas, rather than giving a direct answer, a teacher might point them toward a calendar. This not only teaches them to find answers on their own but could also open a learning moment of history or timekeeping.

In the Montessori classroom, the development of the reasoning mind extends beyond academic exploration to include social and moral growth. An illustrative example of this is the lunchtime routine. During this time, students are tasked with selecting lunch helpers and planning out their roles, a process that requires them to apply logical thinking and collaboration. This scenario teaches them about responsibility, teamwork, and the intricacies of decision-making. By engaging in these activities, students use their reasoning minds to consider the needs and viewpoints of others, balance different roles, and come to collective decisions. This hands-on approach to learning not only fosters a sense of community but also sharpens their ability to think through complex, real-world problems — a direct application of the reasoning mind in social contexts.

Montessori students also extend their learning beyond the classroom through "going-out" activities. These are research activities inspired by their interests, like visiting the Desert Botanical Garden to see how plants adapt to harsh climates. But here's the twist: they plan it themselves, from stating their purpose to organizing the day. It’s a practical application of their reasoning skills, marking their first steps towards independence in the real world.

In essence, the Montessori method is about nurturing curious, analytical minds ready to tackle the challenges of the world. Through storytelling, self-led exploration, and real-world experiences, children learn to question, analyze, and engage with their environment. This balanced approach prepares them not only academically but also as thoughtful, independent individuals ready to contribute to society. Witnessing the growth of these young thinkers serves as a powerful testament to the impact of an education that values the development of the reasoning mind, equipping children for both school and life beyond.

James Qiao

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: January, 2023

The Human Tendencies & the Psychological Characteristics of the Elementary Child

“ As we have seen, tendencies do not change and human tendencies are hereditary. The child possess them in potentiality at birth, and makes use of them to build an individual suited to his time.”

Mario Montessori, The Human Tendencies and Montessori Education

Dr. Montessori observed that all people have certain tendencies, which she identified as the Human Tendencies. These tendencies stay with them throughout their lives. People also have certain Psychological Characteristics which change depending on which plane of development they are in. In the Second

Plane of Development, the 6-12 child displays characteristics that are specific to their age group, while also displaying the universal human tendencies.

In the classroom we must consider these human tendencies when setting up the environment and preparing the child to be within it. We prepare them by supporting their reasoning mind, intellect, and will. The will is formed through making choices, seeing the resulting consequences, and understanding how the choices affect them and their community. This develops the will of the child. The choices children make must be based on knowledge, and the knowledge they need should be in the environment. We first want to get the child used to the environment and want them to understand what the classroom expectations are. This is done through orientation.

The first tendency is “to Orient”. Orientation is the ability to create order in the mind, knowing how to do things or where things are. In the classroom if the child knows how the community runs and where things are it helps them to be oriented. It creates independence and trust within the environment and with those in it. With orientation, we start out at an individual level in the First Plane of Development and then expand out to society in the Second Plane. This tendency is addressed in the beginning of the year so the children can adjust and adapt quickly to the classroom environment. When entering a new environment, be it a classroom or at home, children need to be able to orient themselves to their surrounds. They will need to know what the expectations are.

Another tendency is “to Order”. Order builds the mind through the classification of information, concepts and terminology. Children in the First Plane don’t know how things work but learn through experience and repetition. To help the child we must give lessons related to something they know or something we have done before. If things are given randomly the intellect of the child will not build properly. In the Second Plane, we are building on the intellect and want concepts to be introduced in an orderly way. We give reminders of what we have done and ideas of how we will build on that knowledge.

Next we have the tendency “to Communicate”. Communication uses language as a tool. It gives us power to pass on information. We can sit to create words to express what is in our mind and relate it to ideas. Children in the Second Plane have a reasoning mind and language helps the child develop ways of thinking, expressing themselves, and developing reasoned opinions. Communication is necessary for cooperation in social life. This will be manifested through the children talking. The conversations, discussions and conflicts the children have will further enhance their growth of language. It also helps their communication with others and enables them to share their thoughts and ideas. In fact, it is a necessary tool for collaboration and the sharing of ideas. Without communication the intellect will not grow properly.

Montessori also recognized the tendency for “Exploration”. In the First Plane the child must be oriented before going into exploration. They will explore sensorially to find discoveries and understanding. In the Second Plane the child uses their reasoning mind and their imagination to explore. The classroom materials become less concrete and more symbolic. We must understand the psychology of the child in order to best support their needs to explore.

There is also the tendency “ to Work”. Work is a positive thing which allows us to have concentration in activity. The child will be doing activity with a purpose. This gives a fulfillment to personal goals. Deep concentration and self-satisfying work is key to health development. These activities, goals and deep concentration will lead us to normality throughout our lives.

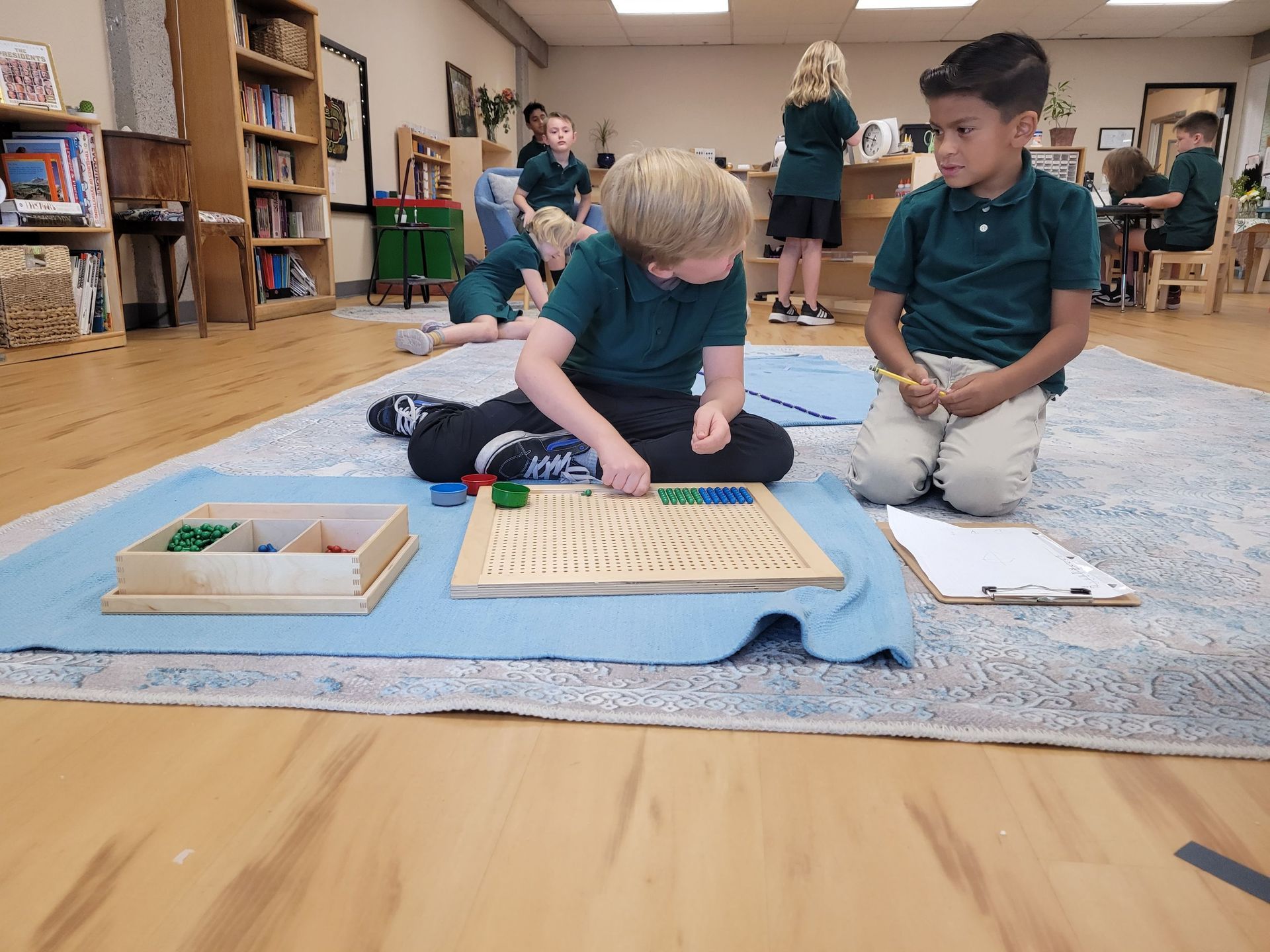

“Repetition” is another recognized tendency. As humans we learn best through repetition. Learning each time through errors that can be changed and perfected. This gives birth to creativity and exploration. The First Plane child does things over and over, without tiring until they reach an inner satisfaction. In Elementary the child isn’t so inclined to do things with the same amount of repetition. The will to repeat comes through variety and making things bigger and bigger; this is called amplification. We see this in the large group work children do in the elementary classroom. They will want to do bigger math problems, large scale timelines, measurements, lists and more.

In order to improve ourselves we need to make mistakes and learn from them, this is part of the tendency “to Self Perfect”. We must derive satisfaction on an individual level by doing better. Each individual has different aspects of themselves that they strive to perfect. As guides, we can help the child to be more aware by asking them “is this your best?’ If we ask in the right way the child usually responds honestly in their self-assessment. This will bring the child to work at the highest level they can reach. In the classroom environment, having consistent individual meetings with the children can help them to assess their own performance within the class.

The Children in the Second Plane also have a a tendency for “Exactness”. Everyone has a different type of exactness. We should honor the child’s way of finding it but also encourage them to take it to the next level. As guides in the classroom we are always making observations of this. If you want to replicate something it needs to be exact. If we have an idea in mind it has to conform to what exists in reality. Our Montessori material helps lead the children in exactness. Showing the child how to check their own work helps them to find their own error and correct it. In Elementary classroom the materials do not have a built in control of error, as they do in the Primary class, which is why we teach the child how to check their own work. This could be through reverse operations in math or using an editing chart for their rough draft writing.

“Abstraction” is another tendency. This is formed within our head and is not something you can touch. Language comes with this, you have an idea and it’s going to need a name. We rely on pulling out the essence of the thought or idea to reach this. It is important for the child to have had sensorial experiences in order to reach this abstraction. First to understand the material in the concrete or sensorial and gradually becoming more symbolic. As it is in their work, children go from concrete to abstract once they have internalized a concept or idea and the material is no longer needed. It is purely in the mind or worked out on paper.

The last tendency is that of “Activity”. Activity is manipulation with the hands. It drives us from idleness to productivity. By using our hands we are connecting to the material in a fundamental way. This can be done using Montessori materials, follow up work, or hand work.

The Human Tendencies have been broken down into separate characteristics to explain them in context, however they all run parallel and contribute to each other. It is the role of the guide to integrate observations and knowledge for the child and to put into practice these tendencies to guide them to being a fulfilled and complete human being. We will know that we have helped meet these tendencies of the children when they become productive workers, respect the environment, and follow established expectations. The children will continue to work towards improving themselves as the will and intellect guide them.

April Knight

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: December 2023

Going Out

“When the child goes out, it is the world itself that offers itself to them. Let us take the child out to show them real things instead of making objects which represent ideas and closing them up in cupboards.” — Maria Montessori

The 'going out' concept is essential for the delivery of cosmic education. 'Going out' is a term unique to Montessori, and although it implies an outing, it distinguishes itself from conventional excursions or field trips through its distinctive characteristics.

What are going outs?

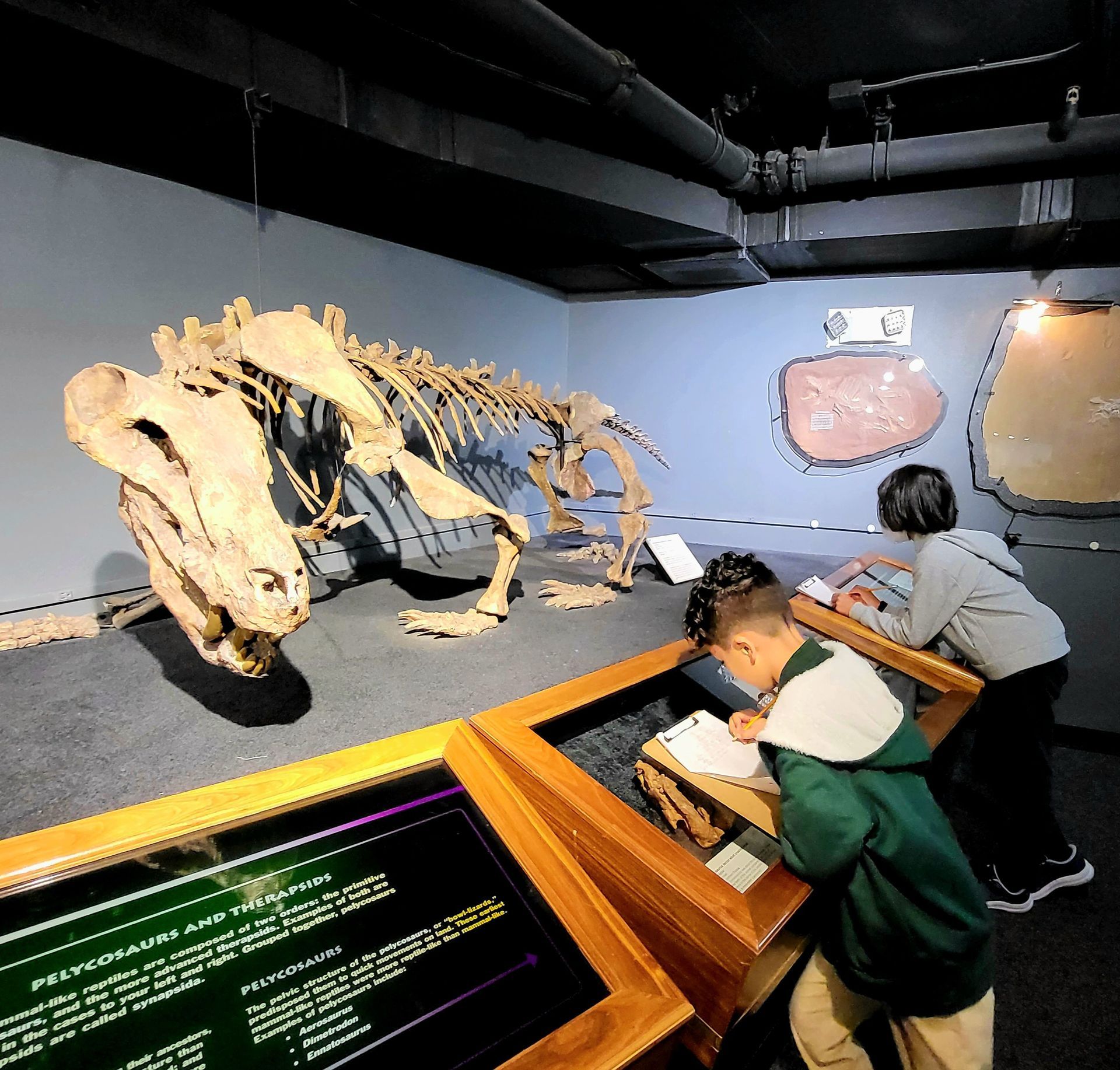

Imagine we are studying a particular topic in the class, like the coming of life. Children become very engaged and they want to learn more about ammonites. After researching and using all the books available in the class, there are still many things they want to learn about. At this point, they can organize a going out to discover more about ammonites. Each child plays a role in this organization; they need to look for a place where they can get more information, how to get there and who can take them, how much it costs, when they can go, what the schedule of the place is… They also need to prepare the questions for the expert. They are the ones who decide if they are going out and where they are going. They do this work collaboratively and without the interference of the adult. Then, after all the planning, the day arrives! Children go to the place and gather the information they need. The adult who is with them, the chaperone, should not intervene in their decisions, neither tell them what to do, they won’t give directions or buy them anything. They are there just to accompany the children and make sure they are safe.

'Going out' in the Montessori classroom is not promoted by the teacher, but rather emerges as a response to the children's classroom activities, with a specific focus on their interests and responsibilities. Children typically work in small groups, engage in various projects, and when they recognize the need for external information beyond the classroom, the concept of 'going out' is born. It is essential to encourage children to explore their diverse interests. Children's own decisions propel these outings, whether driven by their unique interests or responsibilities within the classroom, such as restocking supplies or caring for classroom pets. The children themselves generate these explorations based on their chosen work and particular interests or needs. The possibilities for 'going out' destinations are thus boundless, which reflects the vast range of children's interests and curiosities.

'Going out' is a child-driven process where a small group, typically consisting of two to four children, organizes them. These groups spontaneously come together based on shared interests or common objectives, with no teacher intervention in group assignment. It is crucial to emphasize that children themselves are responsible for arranging the 'going out.' The teacher does not determine the details, such as the destination, timing, or logistics; instead, the children take on the planning and organizing tasks. The teacher's role is to offer guidance and support based on the children's prior experiences and age, without taking charge of the planning process. The goal is for the children to independently arrange these outings to the greatest extent possible.

Why have going outs?

In the elementary years, the child undergoes a significant developmental shift, characterized by heightened consciousness and a thirst for independence and knowledge. This phase is marked by a profound curiosity and a desire to understand the intricacies of the world.

The child looks for mental independence, seeking to explore the reasons and methods behind everything, while also developing a sensitivity to societal interactions. This growing child is inherently drawn to engage in organized group activities and collaborative projects. They begin to transcend the confines of the family and school, naturally gravitating towards the larger society. While not yet a fully mature individual, they are on the path to becoming an independent and responsible member of society. Recognizing this, it becomes evident that, both physically and mentally, the child between the ages of 6 and 12 requires broader horizons, and 'going out' serves as a vital response to meet these developmental needs.

What does the child achieve through going outs?

What we tell the children through going outs is: trust yourself, pursue your passions, and take the necessary steps to follow your heart. Your ideas and interests matter. You hold a valuable place in this world, and you have the power to make choices about where, when, and how you will journey. At first sight, going out can look like just a fun outing, but they are much more than just that. Making decisions without adults’ intervention allows them to:

- Prepare for life beyond family or school.

- Acquire bigger responsibility, independence and develop critical thinking.

- Experience human interdependencies and the exchange of services (when they go to the grocery store, they need to pay for what they need and the cashier will be there to help with that exchange).

- Appreciate and be grateful for others' work (when they go to the museum to learn more about a topic and a person helps them, the children develop a feeling of gratitude towards the person who is sharing their knowledge with them).

- Develop self-control and increase their self-esteem when they succeed in their going out and feel independent.

The going out allows the children to develop the skills necessary to live independently in society, or as Dr. Montessori says it, it makes “the spiritual being … capable of finding his way by himself” (From Childhood to Adolescence 13). One of the most valuable realizations for the child when they venture out is their capacity for responsibility in an expansive environment. When a child has a rich experience and fulfills their needs, they transition to adolescence with a solid foundation to continue their personal development.

Laura Ferrando

Upper Elementary Guide

Published: November 2023

Community

In the vibrant world of Montessori education, community is not merely a concept, it is a way of life that extends beyond the classroom walls. Dr. Montessori's educational philosophy places a strong emphasis on the interconnectedness of individuals, fostering a sense of unity and collaboration. This approach transcends traditional educational boundaries, encouraging a holistic understanding of community that encompasses both the microcosm of the classroom and the macrocosm of the world beyond.

Within the Montessori classroom, community-building is an integral part of the daily experience. Dr. Montessori recognized the importance of a supportive environment where children could learn not only from their teachers but also from one another. The multi-age classrooms promote a sense of family, with older children mentoring younger ones, creating a collaborative learning ecosystem. This structure not only enhances academic learning but also cultivates essential social skills, empathy, and a deep sense of responsibility toward one another.

The Montessori philosophy extends its reach to the home, considering the family as an indispensable component of a child's education. Collaboration between parents and teachers is not just encouraged; it's celebrated. Regular communication ensures that the principles of Montessori education seamlessly transition from the classroom to the home environment, creating a consistent and supportive learning experience. This partnership underscores the belief that education is a collaborative effort involving the child, the school, and the family.

Montessori education goes beyond the traditional curriculum by instilling a profound understanding and appreciation for diversity. Cultural studies are integrated into the curriculum, allowing children to explore and celebrate differences in traditions, customs, and languages. This intentional focus on learning about others fosters a global perspective and nurtures a generation of individuals who are not just academically proficient but also culturally competent and compassionate.

As Montessori students grow, they carry the values of community, collaboration, and cultural understanding into the wider world. The emphasis on practical life skills equips them with the ability to engage meaningfully with the community around them. Whether through service projects, community outreach, or environmental stewardship, Montessori education empowers students to be active contributors to society, emphasizing the importance of empathy and responsibility.

The Montessori approach to community-building is not just about the early years of education. It lays a foundation for a lifelong journey of learning, collaboration, and community engagement. The emphasis on self-directed learning and the ability to work harmoniously with others prepares Montessori graduates to thrive in diverse and dynamic environments, fostering a lifelong love for learning and a deep sense of responsibility to the global community.

In essence, the Montessori theory on community transcends the traditional boundaries of education. It creates a nurturing environment where children not only learn academic skills but also develop essential life skills and values. By fostering a sense of community within the classroom, extending it to the family, and instilling a deep understanding of and appreciation for others, Montessori education cultivates individuals who are not only well-prepared for the challenges of the future but are also compassionate, globally minded citizens.

Hattie Harris

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: October 2023

Storytelling

Storytelling is a cornerstone of the Montessori education, especially in the Elementary years. Dr. Maria Montessori wrote, "The tales and stories which the child hears are meant to enlarge his imagination, stimulate his emotions, and enrich his conceptual powers." At the start of each school year, students are introduced to the Five Great Lessons - grand, impressionistic stories that categorize knowledge into five broad themes: The Coming of the Universe, The Coming of Life, The Coming of human beings, The Coming of Language, and The Coming of Numbers. These five great stories establish the framework of Cosmic Education, providing a meaningful context to explore academic subjects and the interconnections of life.

The Great Stories spark children's imaginations and curiosity about cosmic Education. As Dr. Montessori explained, "The vision of the universe which we wish to give the child is one of majesty, and order, of law, of wonder, and of beauty." The stories do not focus on minute details that may limit a child's conception of possibility. Rather, they paint an inspiring vista leaving room for the child's imagination and questioning. Stories thus motivate self-directed exploration of astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology, and more. Children are compelled to collaborate to piece together the great mysteries of our cosmos.

Beyond the Five Great Lessons, storytelling continues throughout the years. Myths, fables, historical narratives - stories are woven through nearly every subject. We tell the story of early mathematicians developing numerical systems and pioneering geometric principles. Students connect emotionally to the triumph and struggle of history. Stories reveal the interdependence of humanity - how we rely on farmers, builders, inventors, and artists from the past and present. Dr. Montessori wrote, "Man needs to enter into relationship with the universe; he needs to feel himself at one with other living creatures, with rocks, flowers, sunlight, and stars." Stories bind us together.

James Qiao

Lower Elementary Guide

Published: September 2023

Freedom and Responsibility

“The first task is to shake life, but leave it free to develop”

- Maria Montessori

One of the fundamental principles in a Montessori environment is freedom. Freedom is understood as the freedom to choose your work, your workplace, your coworkers; freedom of movement, freedom of thought, and freedom of expression and communication. However, for this freedom to exist, limits are necessary. Common limits which are based on respect for the environment, materials, classmates, and the children themselves. These limits allow the child's freedom. Boundaries must be respected to maintain this freedom, hence the responsibility. Children should use their freedom responsibly.

Freedom is the capacity for self-determination of the will, which is knowing what one wants and where one is going. It is also knowing that decisions have consequences.

Children construct their own learning, taking into account their interests and therefore it is common in Montessori environments to find children working with different materials and exploring different areas of learning. Each of these children has chosen their own work. Not just any type of work, but productive work. This is the first act of responsibility that must be observed in the environment. Is the child choosing their work appropriately? Are they using their freedom responsibly?

Let's look at two examples:

Example 1:

“M.F. chose to start the day by calculating the common factors between two numbers. At 8:35 he sat down at his workplace and started working. At 9:05 he decided to stop his task to have a small snack. At 9:13 he resumed his work. At 9:30 he finished his work. During this time he solved 20 problems.”

Example 2:

“S.T. chose to start the day with her research work on spiders. At 8:46 she sat down at her workplace and started working. At 9:02 she decided to stop her task to have a small snack. At 9:10 she walked around the area. She returned to her workplace at 9:30. At 10:47 she finished her task. During this time she wrote 3 lines.”

These two examples are situations that are observed daily in the environment. The two children had the opportunity to choose their work, they themselves decided what to do. Nobody told them anything or directed them. Obviously one of the two is not using their freedom responsibly, not because they don't want to, but because they are not yet ready for it. The work of one of the two has not been productive. This is where an intervention must be made, limiting this freedom until the child is ready to use it consciously.

However, interventions should not be arbitrary or authoritarian, but rational. At this stage of development, children are developing their reasoning mind and can understand such a limitation if it is explained to them appropriately. For this, weekly individual meetings with the children are essential. In these meetings, the child's weekly activity is assessed. The child records his work daily in a record book. This tool helps both the child and the guide to recognize productive work. It is here, during this meeting, that the limitation of the child's freedom of choice of work is assessed as necessary.

Similarly, freedom of movement must also be observed. Children can move freely around the environment. This means not just getting up to drink water, go to the bathroom, or stop to have a snack, but also to change your workplace whenever you need to. They can start the day working outside, or near the art area, and end it working on the floor or on the experiment table. During the day the flow is enormous. Once again, the observation of the guide is essential. During this time of movement, unless the child’s own integrity or that of her companions is endangered, the guide does not intervene, she only observes. It is during the meeting with the child, with the support of the record book, that it will be assessed whether this freedom of movement was used responsibly or, on the contrary, it was affecting their concentration and productivity. If the latter is the case, the freedom will be temporarily limited by the guide making the work choices for the child.

Communication is an aspect that is promoted in the environment, giving children the opportunity to do group work. During this work, children exchange opinions, share ideas, and make decisions together. Therefore, they decide who to work with. Again, observation is the key.

Let's look at two examples:

Example 1:

“At 9:32 T. and H. are working on a project about the chinchilla. They go outside to paint a poster and make a model of the habitat of this animal. During this time they are observed concentrating and talking about work. At 10:45, S.W., who was working inside the environment, approaches with interest and curiosity and asks about the project. In the end, S.W. decides to help them in the investigation. They continue working until 11:30, when it is time to clean up."

Example 2:

“At 9:32, T. and H. are working on a project about the chinchilla. They go outside to paint a poster and make a model of this animal's habitat. During this time they are observed concentrating and talking about work. At 10:45 a.m., L.L. , who was inside the environment, approaches and catches their attention. L.L. is doing something silly and the other two children laugh. They are seen playing and talking about topics unrelated to work. At 11:30 it is clean up time.”

These two examples are situations that are observed daily in the environment. S.W. and L.L. had freedom of movement and communication. They voluntarily decided to go outside to talk to their companions. However, in one of the two situations, a responsible use of freedom of communication was not observed. Not only was the conversation not about the work at hand, but the concentration of others had also been interrupted. This is where an intervention must be made, limiting this freedom until the child is ready to use it consciously. This fact will be discussed again in the individual meeting with the child.

Finally, freedom of thought, being able to think without being judged, is essential. How else could decisions be made? When a child makes a decision, he does nothing other than execute a thought. This thought should never be judged without first observing the result. It is common in the environment for children to choose a follow up work to practice a lesson. Each child knows what they need for this. No choice should be taken lightly.

For example:

“After receiving a lesson about the parts of the mountain, C.L has decided to bake a cake in the shape of a mountain and point out its parts. Other classmates have helped. Later this work of the mountain was shared with the classroom community. The result was a sweet follow up work that everyone enjoyed”

Another example:

“After receiving a lesson on the diagonals of a polygon, L.R. has decided to make a poster with different polygon designs. They chose to work alone. After 2 hours only 3 designs were drawn. The child did not point out the diagonals. This results in unfinished work that ends up in the poster basket. No presentation to the community is expected. ”

In both cases the child's freedom of thought has been respected. No one has told them which follow up work was better, nor has their choice been judged during its execution. It is only when seeing the result that it is possible to assess whether the decision made was responsible, and, again, this aspect will be discussed in the meeting with the child.

In conclusion, as Maria Montessori pointed out, the child must be allowed to work freely, accompanied with reasonable limits until they are prepared to use that freedom responsibly.

Silvia Fortuny

Upper Elementary Guide

Published: August 2023

Cosmic Education

The Montessori Method of education was established by Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and scientist, as an aid to life. She recognized the need for a different type of education, one that was based on the developmental needs of children and saw the inherent power of the child to create the person they were to become. This was, and continues to be, a revolutionary method of education, which takes into account the whole child and allows each individual being to actualize their unique potential.

In the Elementary classrooms, we provide “Cosmic Education”. According to Webster’s dictionary, “Cosmic” means “of or relating to the universe” and “Education” means the “acquisition of knowledge or skills”. In its most basic sense, Cosmic Education is a way of educating in context to the universe; a way of seeing the inter-relatedness of all that is within the universe.

“Cosmic education is a way to show the child how everything in the universe is interrelated and interdependent, no matter whether it is the smallest molecule, or the largest organism ever created. Every single thing has a part to play, a contribution to make to the maintenance of harmony in the whole. To understand this network of relationships, the child finds that he or she also is a part of the whole and has a part to play, a contribution to make.”- Phyllis Pottish-Lewis